This is the fifth and final part of a series on the fiftieth anniversary of the First Quarter Storm. For details and citations please consult my dissertation, Crisis of Revolutionary Leadership.

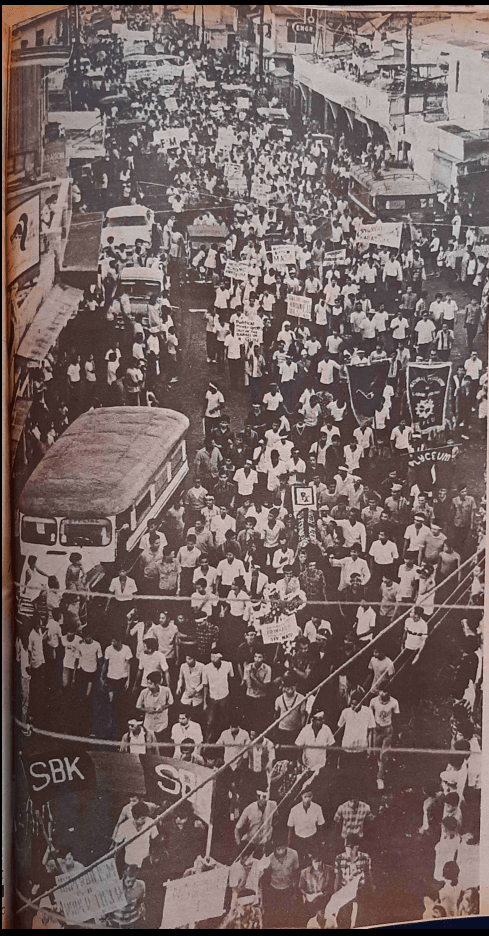

March 3: People’s Anti-Fascist March

Denied access to Plaza Miranda, the MDP adopted a new strategy — “People’s Marches” — and on March 2 they circulated a leaflet announcing a “People’s Anti-Fascist March” to be held the next day.

The leaflet cited the raid on the PCC as evidence of the fascism of the state and insisted that despite this fascism the movement would continue. It called on everyone to join the march, which was to begin at one in the afternoon at the Welcome Rotonda. The MDP was able to promote the march on national television, as at the beginning of the month, Lopez had provided the MDP with a weekly television program which broadcast from nine-thirty to ten-thirty on Thursday nights on ABS-CBN. The SDK, KM, and MDP were given extensive access to radio as well, where the Lopez family and others in the media industry supplied them with regular free airtime. The MDP ran a daily two hour program, Impressions of the Nation, hosted by SDK member and future NPA leader Rafael Baylosis, with the explicit intent of broadcasting material regarding imperialism, feudalism, and fascism and the program of national democracy. The KM and SDK were provided with their own separate radio broadcasts as well.

The KM issued a leaflet, calling as always for the “continuation of the struggle for national democracy.” The developing struggle, they claimed, was evidence of the “growing revolutionary consciousness of the Filipino people who are fighting to destroy the evil forces of exploitation and suppression.” Fascism, the leaflet claimed, was the last weapon of American imperialism and was being deployed to hide the weakness of their puppet Marcos, who had lost the trust of the masses, something a government needed in order to succeed, as a result of the unceasing struggle of the forces of national democracy.

The MPKP published their own leaflet for the march, responding to charges of violence which were being raised against the protest movement. It stressed that the root of violence was the “fascist repression and brutality” of the “neocolonial bourgeois state,” and “an oppressed and exploited people have a right to meet force with force.”

Seeking, however, to blame the KM as well, the MPKP continued

The national democratic forces do not plan or participate in or condone acts of ‘vandalism’ or violent acts on the persons and properties of individuals who are not their violent enemies. These are the isolated deeds of provocateurs, looters, and thrill-seekers, or of emotional and extremist elements whose wrath is understandable but whose leaders are duty bound to guide them into a recognition of the distinction between enemies and friends.

Provocateurs must be identified and exposed as mercenary tools of the imperialist-fascist puppet factions now intensely engaged in their own fierce competition for neocolonial power and authority. Extremist and anarchistic elements must be led into the correct revolutionary line, or consciously isolated should they prove to be intractable …

Expose Mercenary Provocateurs! Struggle Against Anarchists!

A highly sympathetic account in the Collegian reported that as the march past through Binondo “the Chinese have boarded up. The marchers scream at them before them [sic] are calmed by their leaders and their fury redirected at police brutality and colonialism.”

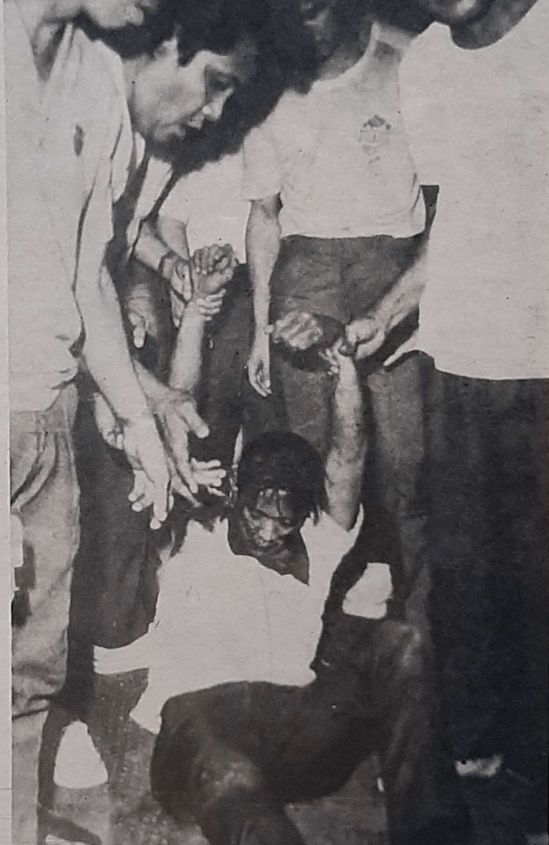

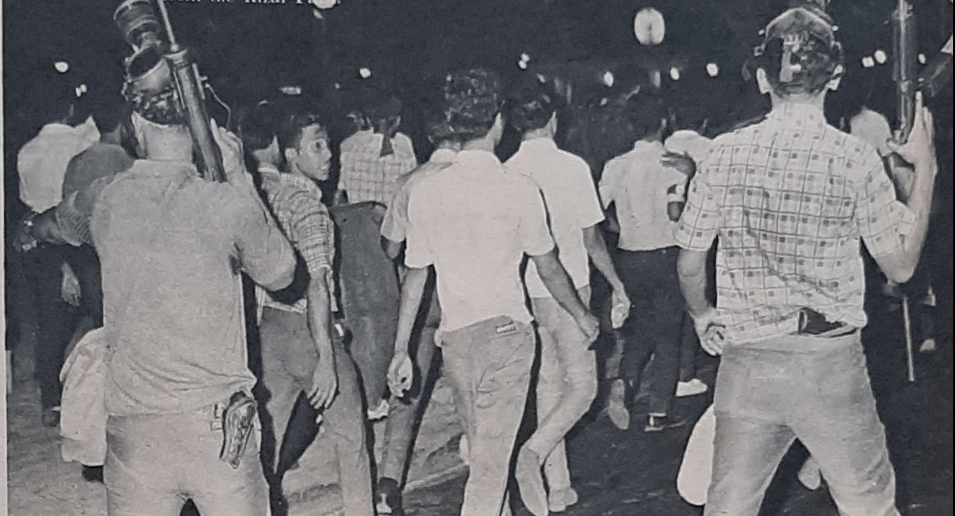

At the end of a circuitous route through Manila, approximately twenty thousand marchers converged on Plaza Lawton, where they were violently dispersed by police who set upon them with truncheons. Fleeing to Intramuros, Enrique Sta. Brigida, a freshman in Commerce at Lyceum and a member of the Lyceum Student Reform Movement, was killed by a blow to the skull. The CPP published a statement on the March 3 People’s March in the June 1 issue of Ang Bayan, which hailed Enrique Sta. Brigida for “adding one more to the list of heroes who have sacrificed their lives.” “However,” the article continued, “the bloody suppression of the March 3 People’s March failed to intimidate the masses of workers, student [sic] and youth who joined the historic mass action. It only goaded them more to wage a resolute struggle for national democracy.”

On March 10, three thousand students marched from Lyceum to South Cemetery in a funeral procession for Sta. Brigida that was at the same time a protest rally. Renato Constantino, Amado Hernandez, Jesus Barrera, Voltaire Garcia,and Crispin Aranda spoke at the funeral, and Lyceum President Sotero Laurel led the procession. It was Hernandez last political act, as he died two weeks later.

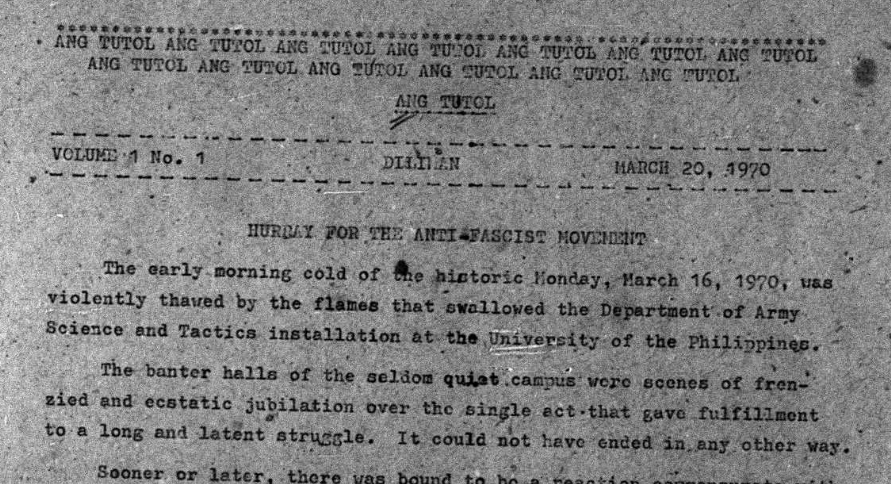

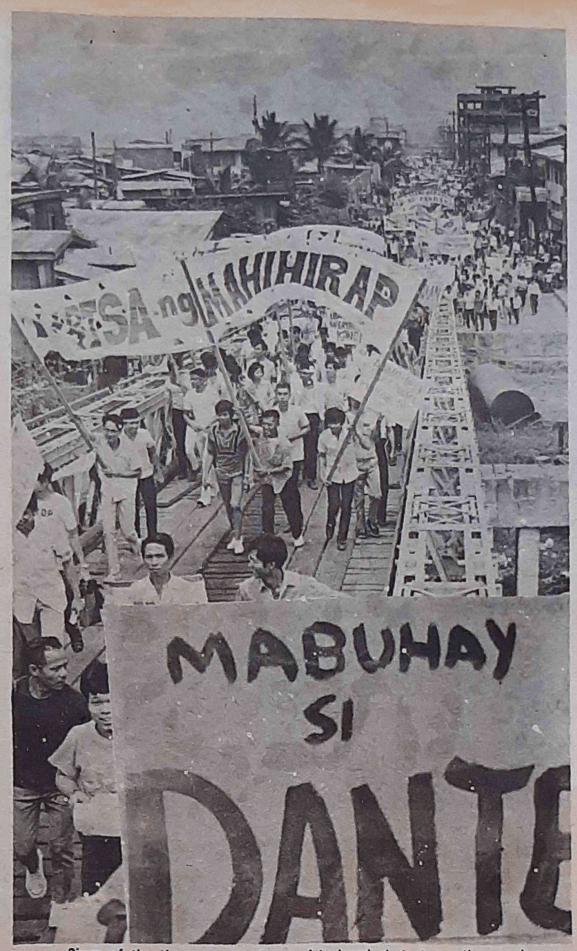

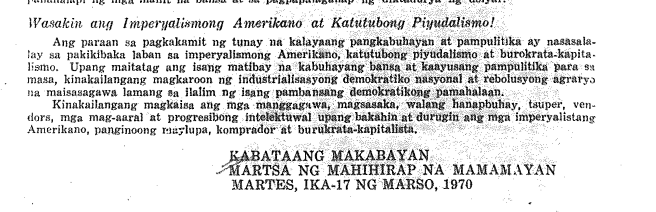

March 17: Anti-Poverty March

The MDP held a meeting on Saturday March 14 to finalize plans for another march, to be held on Tuesday the seventeenth and to be called “an anti-poverty march.” The event became known in Tagalog as the Martsa ng Mahihirap,” or the Poor People’s March. Olivar told the press that the MDP “takes the uncompromising position that poverty is historically a mere consequence of the exploitative semi-feudal and semi-colonial character of our society.” In the early morning of the sixteenth, the ROTC and armory buildings on the UP campus burned to the ground. The Collegian wrote, “On the eve of final exams, dormers scampered out in night clothes to watch the DMST [Department of Military Science and Tactics] giant hut, seen by many as sanctuary of local fascist authority, burn down as dormer-activists shouted ‘Maki-BAKA, huwag MA-TA-kot.’” A leaflet, put out under the name Ang Tutol [The Protest], hailed the burning of the DMST building as a victory of the national democratic movement over the fascist state.

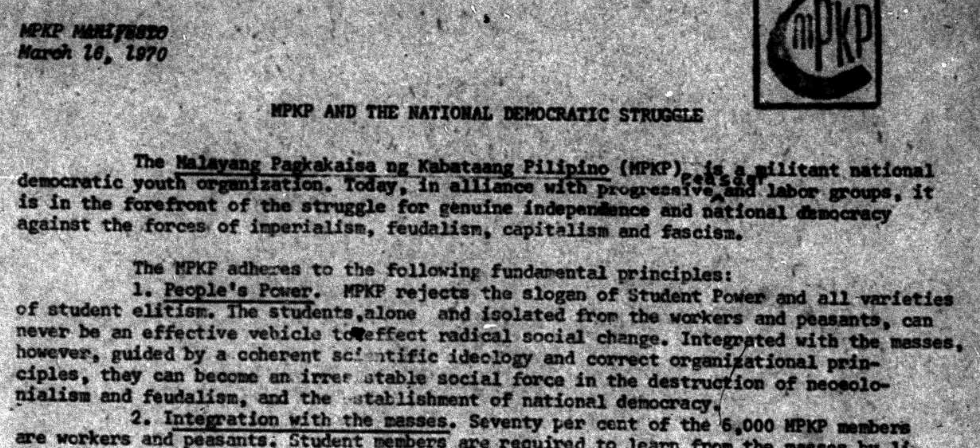

The day before the anti-poverty march, the MPKP published a leaflet proclaiming that the organization adhered to four basic principles.

The first was people’s power, a formulation which they opposed to “student power,” writing, “MPKP rejects the slogan of Student Power.” The second basic principle was integration with the masses, which they asserted was not merely “philanthropy,” targeting with this remark the SDK controlled campus organization, the Nationalist Corps. True integration with the masses, the MPKP wrote, was reflected in the fact that seventy percent of the six thousand members of the MPKP were workers and peasants. The third principle was “revolution from below,” stating that the “MPKP rejects Marcos’ concept of ‘revolution at the top’ … revolutionary change can only be brought about by democratic action from below. It cannot come as concessions from the oppressors and exploiters.” The final principle was “Internationalism.” By this, the MPKP did not mean the international struggle of the working class for socialism, but rather referred to the need to promote the interests of the Soviet Union, writing that “MPKP deplores the current efforts of reactionaries to inculcate chauvinist emotions in the anti-imperialist movement.” With these principles, the MPKP attempted to distinguish itself from the SDK (first principle), the NC (second), the Marcos administration (third), and the KM (fourth).

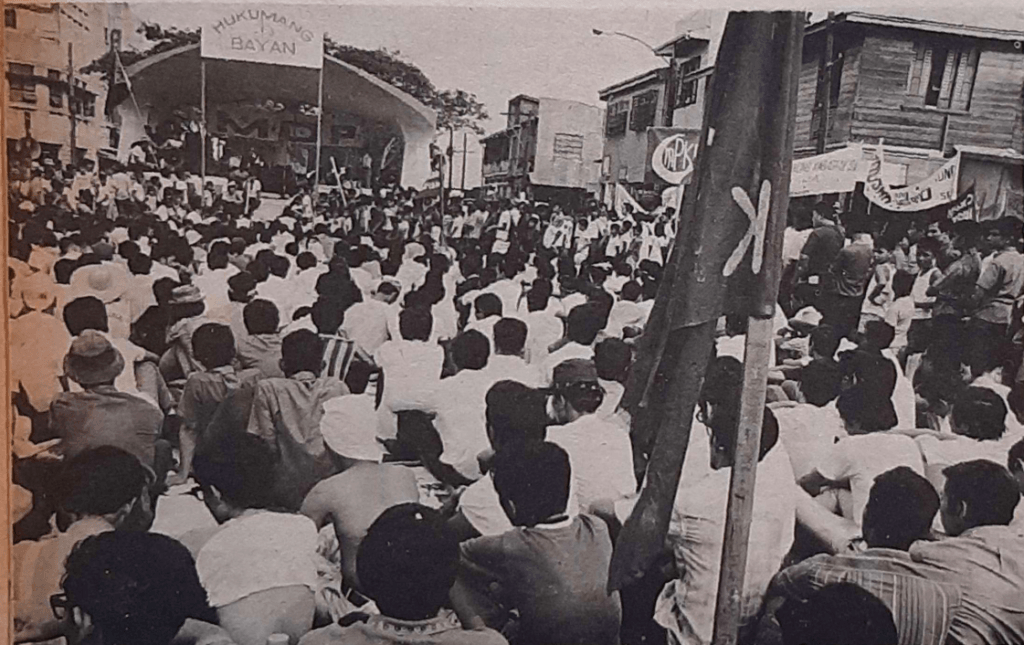

On Tuesday, March 17, the MDP launched its anti-poverty march. The march began at nine in the morning at three locations and converged on Plaza Moriones in Tondo to stage what they termed a People’s Court [Hukuman ng Bayan]. The speakers at the rally accused Marcos and his cohort of a list of crimes “against the Filipino people,” pronounced a death sentence, and publicly hanged their effigies.

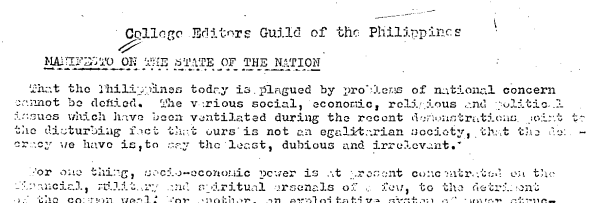

The College Editors Guild of the Philippines (CEGP), which was increasingly entering the camp of the KM, issued a statement, “We call for egalitarianism, which diffuses socio-economic and political powers from the few to the many, from the present ruling oligarchy to the people at large … The CEGP sees two valid and realistic means: one peaceful, the other violent … [which means are used] is highly dependent on how the forces of reaction — the beneficiaries of this highly exploitative system — will react.” Either, the CEGP claimed, the elites would allow “an authentic Constitutional Convention … [of] delegates without vested interests and unbrainwashed,” or they would face violent revolution. The statement concluded: “Ours is a democracy for the elite, a bourgeois democracy, and must be replaced by a genuine national democracy of, for and by the Filipino people.” Because this was a march against poverty, the leaflet mentioned socialism twice and even mentioned the 1917 Russian Revolution. Its political conclusions, however, were strictly limited to pressuring the elite — with the threat of violence — to carry out national democratic measures.

The KM distributed a leaflet which developed its analysis somewhat. While it pointed to the “mounting fascism” of the Marcos administration, this was no longer depicted as its subjective response to the mass protests, but was rooted in the larger crisis of US imperialism. In its attempts to resolve this crisis, the United States was compelled to increase its exploitation of its semi-colonies and this required the growing use of the repressive apparatus of the state. In this aspect of their analysis, the KM was correct. The architecture of dictatorship being erected in the Philippines paralleled the rise of dictatorship around the globe beginning in the mid-1960s and was an expression of the crisis of US imperialism. The international character of this threat highlighted the bankruptcy of local, nationalist solutions to the crisis. Only the coordinated international struggle of the working class for socialism could respond to the international drive to military dictatorship from Chile to Greece and from Indonesia to the Philippines. The KM drew no new political conclusions from this analysis however, and still called for a broad united front in the struggle for national democracy. The solution to the problems of poverty and the threat of dictatorship in the Philippines, they asserted, was national industrialization and agrarian revolution under a national democratic government. What is more, in their subsequent analyses and leaflets, the KM reverted to their older conception, claiming again that the ‘fascism’ of the Marcos administration was rooted simply in the subjective response of Marcos to the protest movement.

The MPKP also circulated a leaflet at the March 17 rally, which stated that “One of the many questions of people regarding the issues raised by the demonstrators is what is meant by imperialism, feudalism and fascism.” The key, the MPKP argued, to ending poverty was national industrialist development of the “basic industries,” in particular, the creation of complex machinery using metal from Philippine mines. However, “because the prevailing system is bad, it needs to be changed and not merely the people. Even if we get good leaders if the system itself is rotten, they will still not succeed because they themselves will become its victims.” The MPKP made no reference to any specific political event or person, and Marcos was never mentioned. The logic of their leaflet however, could easily be interpreted to argue that Marcos himself was a good leader but the rotten system was corrupting him. It was not a stretch of logic to assume that if the system could be repaired then Marcos could be rescued to be the good leader that he had always intended to be.

Ang Bayan claimed that “hundreds of thousands of people” participated in the anti-poverty march. The numerical estimates of revolutionary strength being issued by the CPP were increasingly out of keeping with reality. In the same issue of Ang Bayan, they asserted that “more than 90 per cent of the masses … are on the side of the revolution.” These figures were not merely dishonest, they were absurd. If ninety per cent of the masses were on the side of the revolution in any meaningful sense of the word, the party would have already taken power.

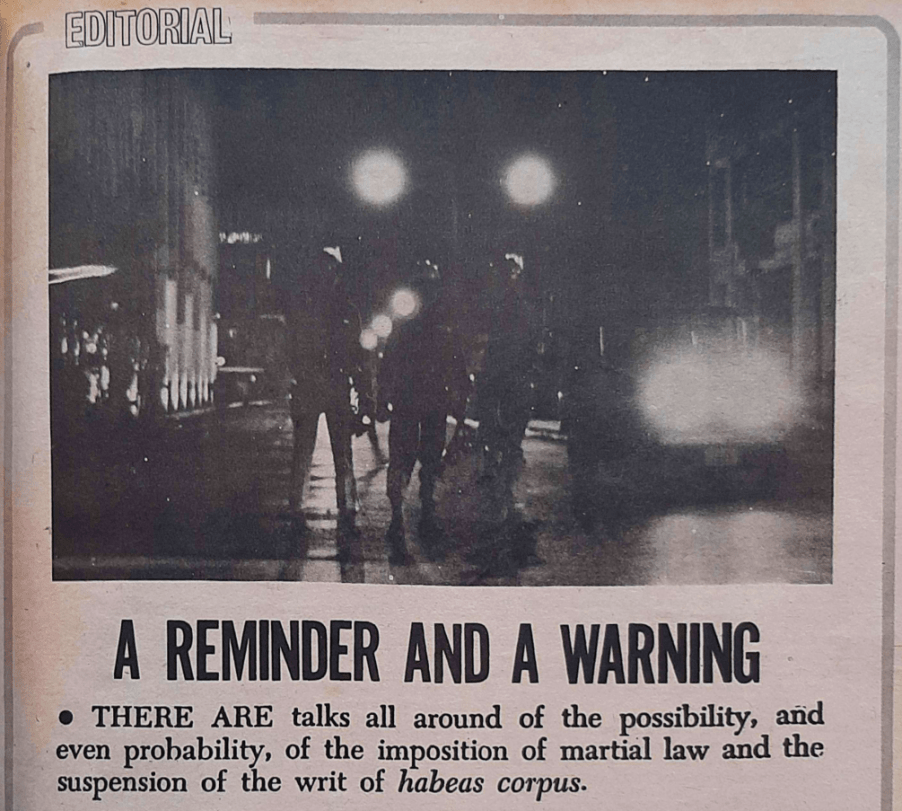

The Storm Subsides

The First Quarter Storm was a student protest movement, and while the majority of these students were intimately connected to the working class and peasantry, the FQS never moved beyond its social base in the student population. At no point did the leadership of this movement, which rested largely with the CPP, fight for its independence from the bourgeoisie and the traditional political elite. On the contrary, it consciously and secretly pursued the interests of a faction of the ruling class and profited out of the relationship.

At the same time, the CPP did not orient the protesting students to broader layers of the working class. The chanted slogans and newsprint manifestos all directed the students merely to escalate their denunciations of Marcos and “fascism,” and ultimately to join the armed struggle in the countryside.

For all its fiery rhetoric and pitched battles in the street — and no matter how truly courageous and self-sacrificing many of the young people were who joined its ranks — the First Quarter Storm was, in the end, but a violent venting of steam. The political turbines through which this steam coursed were those of Lopez and Osmeña, with their scheming plots, and Marcos, who steadily readied the architecture of martial law.

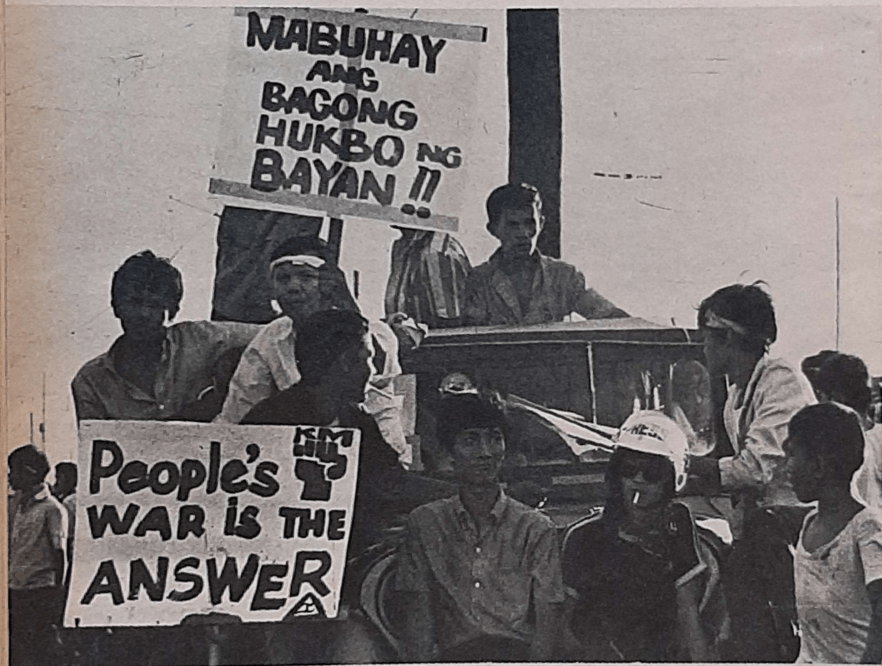

On April 5, the MDP and an organization calling itself Crusaders for Democracy held a rally of five thousand people at Plaza Miranda. Nonie Villanueva spoke for the KM, telling the crowd that People’s War was the answer to the “threat of martial law.” The crowd moved from Miranda to the Embassy, but the police attempted to divert the demonstration with tear gas as it neared Manila City Hall. The protesters responded with Molotov cocktails and pillboxes, and the Metrocom fired their guns to disperse the crowd. It was the last gasp of the First Quarter Storm.

As a movement composed almost exclusively of students the storm’s life was necessarily a short one. Graduation rites succeeded final examinations, and the second week of April saw the majority of students returning home to the province or taking up full-time summer work. As the semester ended and Lopez temporarily reconciled with Marcos, the storm subsided as rapidly as it had started. On March 22, Marcos addressed the graduation rites at the Philippine Military Academy (PMA), vowing to impose martial law “in case the communist threat becomes a positive danger that would imperil the security of the country.”

On April 11, UP staged its graduation rites and the MDP produced a leaflet which it distributed to the class of 1970. It expressed its “firmest fraternal support for the planned protest actions at this year’s UP commencement exercises by graduating national democratic activists,” and denounced US imperialism and their Filipino and Chinese accomplices in the Philippines. The denunciation of the local Chinese accomplices of US imperialism was a striking addition to the rhetoric of the national democratic movement and it would develop rapidly into explicitly racist attacks on the kumintang intsik [Guomindang Chinese], playing an increasingly prominent and noxious role in the propaganda of the KM, SDK, and their allies over the next year.

The First Quarter Storm was over.