What follows is the fourth part in an ongoing series on the fiftieth anniversary of the First Quarter Storm (FQS), the explosion of protests at the beginning of the 1970s in Manila. For details and citations please consult my dissertation, Crisis of Revolutionary Leadership.

In the wake of the violent January 30 Battle of Mendiola, the forces of the protesters and the state regrouped. Four dead youths were buried. Marcos arranged to meet with the leaders of the developing storm, including the SDK and KM, and secured a commitment to call off the next major demonstration. Communist Party leader Joma Sison intervened, instructing the KM to demand that the previously announced People’s Congress at Plaza Miranda go ahead as planned. The First Quarter Storm regained momentum, but where was it heading?

Aftermath

The day after the Battle of Mendiola, Marcos delivered a nationally televised address, denouncing the demonstrators as “Communists” and warning that he would respond to such demonstrations with the force of military arms.

To the insurrectionary elements, I have a message. My message is: any attempt at the forcible overthrow of the government will be put down immediately. I will not tolerate nor allow communists to take over … The Republic will defend itself with all the force at its command until your armed elements are annihilated. And I shall lead them.

Everyone began to speak of martial law. E.L Victoriano, wrote in the Philippine Herald on February 1, “Widespread disturbances throughout the country would give [Marcos] the excuse to declare martial law with all its unlimited executive powers.” A wave of fear swept through the better-off layers of society; Saturday morning saw panic buying in the supermarkets and military patrols in the streets.

Government troops made no effort to be inconspicuous: though supposedly no longer on red alert, they roamed the city in rumbling trucks from which carbines and Armalites stuck out like sore thumbs, and occasionally made forays into the universities. Banks and stores started boarding up their glass facades with plywood or steel sheets. The stock market didn’t crash, but the prices of stock took a sharp plunge that brought about an orgy of short selling. Refugees from Forbes Park nervously paced the carpeted floors of the Hotel Inter-Continental, filled to capacity for the first time since its inauguration. Classes in Greater Manila were suspended for a whole week, and for a whole week the mayors of Manila and Makati refused to grant permits to demonstrate.

A series of recriminations, threats and demands filled the daily papers. Commander Dante sent a letter to Marcos warning that “the New People’s Army would exact reprisals from senior Government agents for incidents of this type.” Jopson and Ilagan issued a statement, on behalf of the NUSP and NSL, demanding the ouster — “not mere retirement,” they insisted — of Gen. Vicente Raval, head of the PC. Manuel Alabado, Executive Vice President of the US Tobacco Corporation Labor Union testified before Tañada’s joint congressional committee that he had been kidnapped on January 26 by five soldiers and made to assert that he was a Huk and that the Huks were behind the demonstrations. He claimed to have escaped and to have sought refuge with Ignacio Lacsina.

Immediately after the events of January 30, the CPP published a statement in Ang Bayan — “On the January 30-31 Demonstration” — hailing the “four student heroes” who had been killed. The CPP argued that the violence of January 26 and 30 indicated that the entire Filipino people are increasingly awakened to the need for armed revolutionary struggle in the face of armed counter-revolution.” (40) The demonstrations “have served as a rich source of activists for the national democratic revolution and, therefore, of prospective members and fighters of the Communist Party of the Philippines and the New People’s Army.” (44) Ang Bayan saw in the violent suppression of the students — who had gathered behind a confused array of political banners — the ideal scenario for recruitment to the armed struggle, and concluded excitedly, “The revolutionary situation has never been so excellent!” (45)

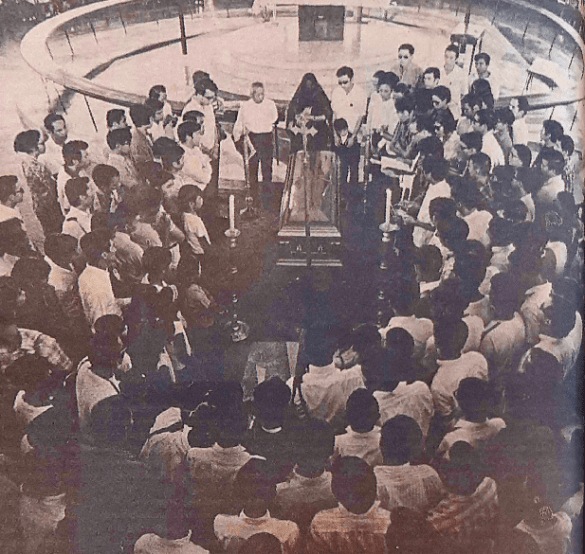

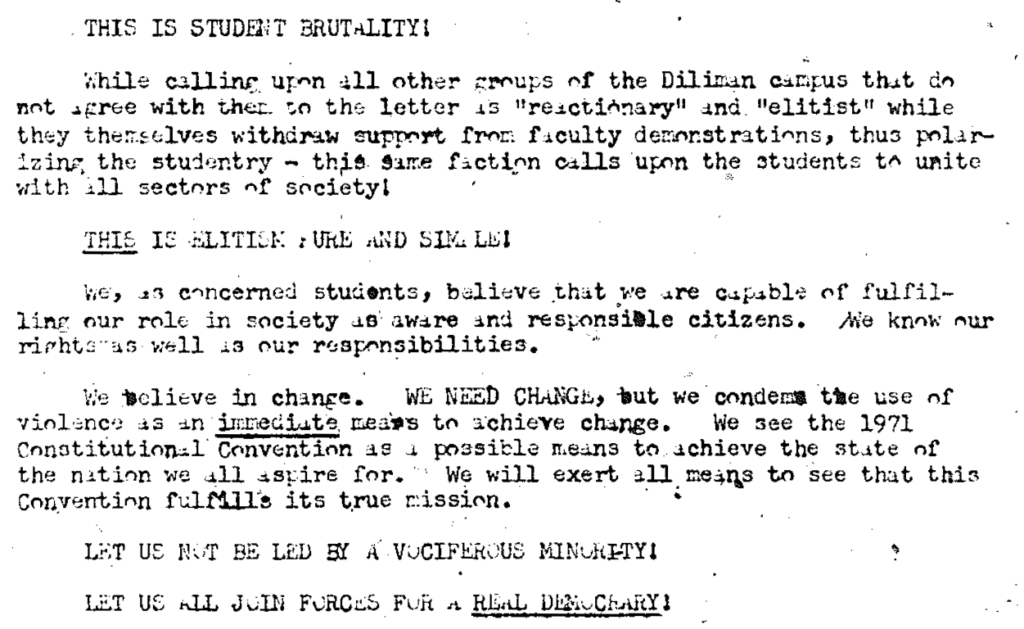

The funeral rites for the four who had been killed on January 30 saw a massive turnout of students. Jerry Barican and Dick Gordon — political rivals on the UP campus — served as Alcantara’s pallbearers. The peaceful cooperation lasted for the duration of the funeral, as a group of UP students, led by Manuel Ortega and Dick Gordon, issued a manifesto and a declaration of principles on February 2 denouncing both police brutality and what it called “student brutality.” It condemned the “violent,” “rabble-rousing,” “vociferous minority” among the students who were responsible for the violence of the protests. The phrase “student brutality” would become a mantra of right-wing elements on the UP campus over the next two years, particularly under the leadership of Ortega.

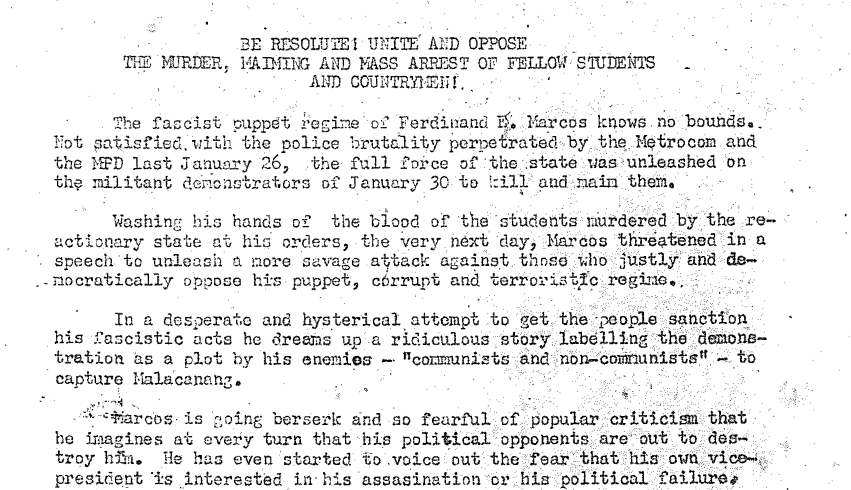

Marcos began claiming that his political rivals were acting in cahoots with the “Maoists” to overthrow him, and on February 2, the KM published a response. Marcos was “going berserk and so fearful of popular criticism that he imagines at every turn that his political opponents are out to destroy him. He has even started to voice out the fear that his own vice president is interested in his assassination or his political failure.” Marcos’ fears were not mere paranoia; there was in fact a conspiracy between Lopez and the CPP and the KM leadership knew it. The KM was receiving financial support from Lopez to prepare and mount their demonstrations.

Marcos, the KM continued, “having been given the go-signal by his imperialist masters” had entered into relations with “the Russian ‘communists.’” At the same time, however, he was denouncing the “Maoists” in the Philippines, who were, he claimed, attempting to seize power on January 30. In this Marcos revealed his “appalling ignorance,” the KM claimed. First, they insisted “the theory of protracted people’s war that applies to a semi-feudal and semi-colonial country like the Philippines does not permit that a mass action as that of January 30 would suffice to overthrow the present reactionary state.” What is more, the KM was at pains to be clear that “the issue is not yet communism. We are clearly fighting for a national democratic revolution.”

Determined to dispel the claim that they were fighting for socialism, the CPP published a statement, “Turn Grief into Revolutionary Courage,” signed by both Guerrero [Sison] and Dante on February 8. To Marcos’ claim that the demonstrations were led by “Maoists” who were “raising the issue of communism,” they responded, “We communists recognize that the nature of Philippine society is semicolonial and semifeudal and that the pressing issue is national democracy. The issue now in the Philippines is neither socialism nor communism.” What is more they were not fighting for an uprising of workers, but insisted rather that:

The Communist Party of the Philippines and the New People’s Army are not putschists. They firmly adhere to Chairman Mao’s strategic principle of encircling the cities from the countryside. All counterrevolutionaries should rest assured that the day will surely come when the people’s armed forces shall have defeated the reactionary armed forces in the countryside and are ready to act in concert with general uprisings by workers and students in the final seizure of power in the city.

The CPP was not fighting for socialism, and it would not act in concert with an uprising of workers until the people’s war had won victory in the countryside. While this people’s war would be of a protracted character, Sison and Dante insisted that “fascism” hastened its success, for “the use of counterrevolutionary violence, restrictive procedures and doubletalk will only result in more intensified revolutionary violence.” Sison and Dante gave direct political instructions to the student protesters. The Party would distribute to “militant demonstrators” three works for their political education: Guide for Cadres and Members of the CPP, Selected Works of Mao Zedong, and Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong Students should form “propaganda teams (of at least three members).” Such a team

assumes the specific task of arousing and mobilizing the students and workers in a well-defined area in the city; or the students, peasants, farm workers, national minorities and fishermen in a well-defined area in the provinces.

The mass work of student propaganda teams in urban areas and in provinces close to Manila will result in bigger and more articulate demonstrations and more powerful general strikes. The mass work of student propaganda teams in the provinces will create the best conditions for getting hold of a gun and fighting the armed counterrevolution successfully.

Sison and Dante concluded by assuring students that “they shall certainly be approached by the Party for recruitment or for cooperation on the basis of what they have already contributed to the national democratic revolution.”

Negotiations

On February 9, classes resumed across Manila, and the Movement for a Democratic Philippines (MDP), which was emerging as the umbrella organization of the protests, secured a permit to stage a rally at Plaza Miranda on the twelfth. Looking to negotiate a commitment to call off the demonstration, Marcos held a five hour long meeting in Malacañang with the MDP leadership. Representing the MDP and NATU were Ignacio Lacsina, who — undisclosed to the others — was working as a regular informant for Malacañang; PCC President Nemesio Prudente; Teodosio Lansang; Felixberto Olalia; Carlos del Rosario; Jerry Barican; and Ramon Sanchez, “among others.” The SDK had at least two representatives in the room; the KM at least one.

The MDP presented thirteen concrete demands to Marcos, “among them the dissolution of the Special Forces, the disbandment of the Monkees, the dropping of charges against the Dumaguete Times newsmen,” and five long-term demands, “nationalization or transfer to public ownership of oil, mining, communications, and other vital industries; nationalization of all educational institutions to thwart commercialization and sectarianism; abrogation of all inequitous treaties with the United States; promotion of trade and cultural relations with all countries, whatever their political color; implementation of land reform by expropriating big landed estates.”

Marcos warned the MDP representatives of the danger that the protests and instability would be used as a pretext for a right-wing coup. Rotea reported that Prudente responded “If that is your only fear, Mr. President … then arm us, lead us, and we will fight and rally behind you! We are ready to die for you if you are sincere in helping the Filipino people!” The Collegian wrote

Representatives of the Nationalist-Progressive sector met with President Marcos at Malacañang for a five hour conference on the issues and developments that arose from the January 30 bloody demonstrations. …

They [the representatives] also deplored the overt attempts of some sectors in the ruling oligarchy to convert student activism into a Hate Marcos campaign to conceal its own share of the guilt for American domination and local feudalism afflicting Philippine society They reiterated their position that the Marcos administration is only a small segment of the ruling oligarchy and its downfall by right-wing conceptation [sic] and agitation can only bring about a military and repressive government.

Marcos declared his intention to “grant what he could, to study what he could not,” and in return the MDP representatives agreed to call off the Plaza Miranda rally and to hold small “localized demonstrations” to discuss issues. They stated that “this move would entail minimum security risks since smaller groups would be easier to control.” Tera wrote on this: “Out of fear of a coup d’etat by the extreme Right [meaning the concerns of Marcos about the plottings of the Lopez-Osmeña bloc] Marcos immediately called for a dialogue with the leaders of the nationalist groups, including the MDK [sic], SDK, MASAKA, NATU, KM, Molabe and others. In a closed door meeting at the palace … Marcos acceeded [sic] to 13 of their demands.”

Sison immediately responded, instructing the KM to distribute a leaflet which denounced fears that Marcos might face a military coup d’etat if the protests continued. The KM put forward the simple-minded argument that “Events have shown that Marcos is rightist and bad enough to deserve the denunciation of the Filipino people … We must always bear in mind that Marcos stands as the chief agent of US imperialism and domestic feudalism in our society.” Sison later stated that “I consider as my most important contribution to the First Quarter Storm of 1970 the reversal and undoing of the agreement entered into with Marcos by leaders of major mass organizations calling off the mass action scheduled for February 12 in protest against the outrageous killing of six students and other barbarities on January 30-31, 1970.”

February 12: the First People’s Congress

Headlines on the morning of the twelfth announced that the Miranda rally had been called off and that separate rallies were to be held on individual campuses. There was widespread speculation that the MDP leaders had been “bought off.” The Collegian, for example, ran the headline “Demonstration goes on tomorrow in UP: Plaza Miranda plan put off due to ‘risk.’”

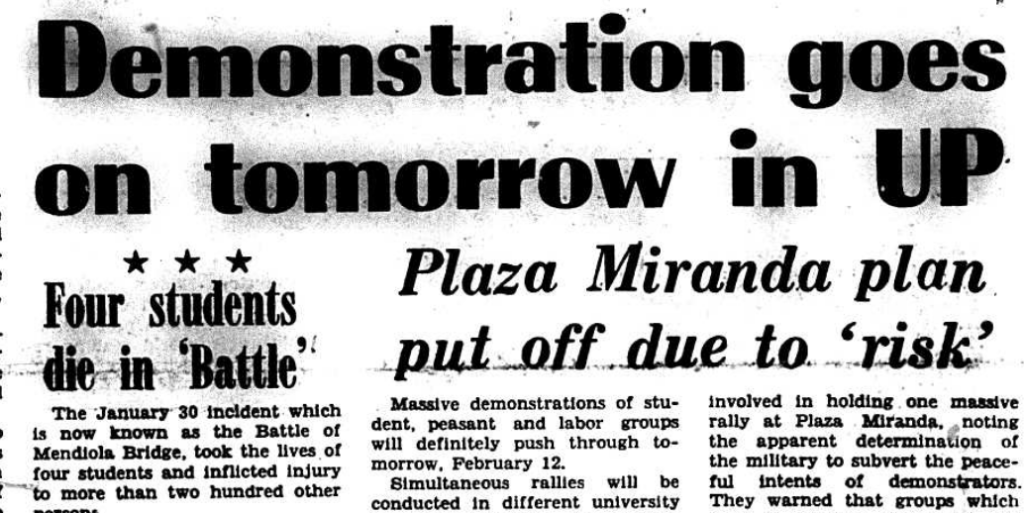

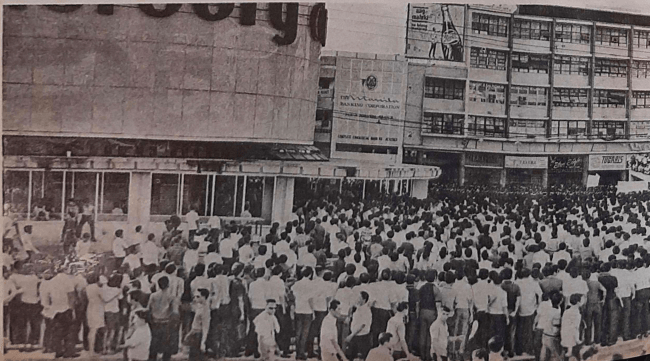

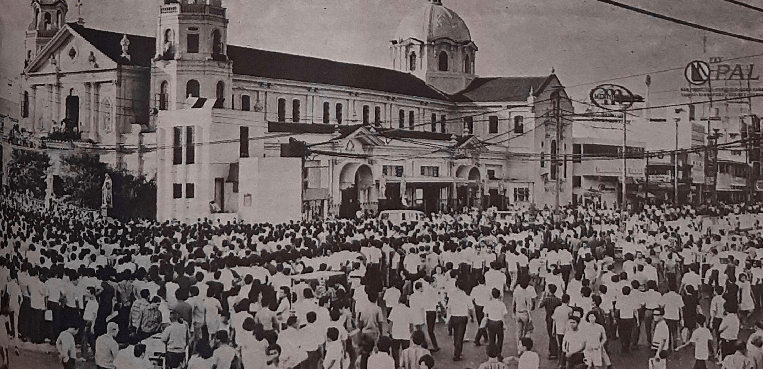

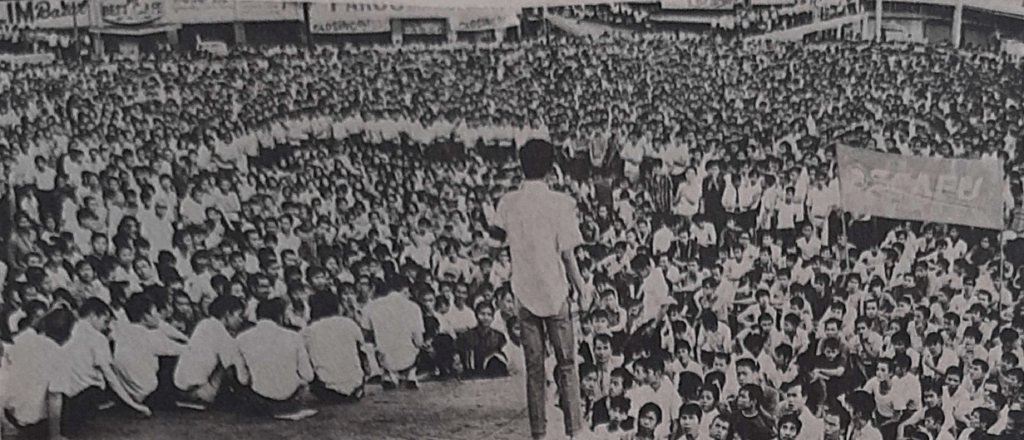

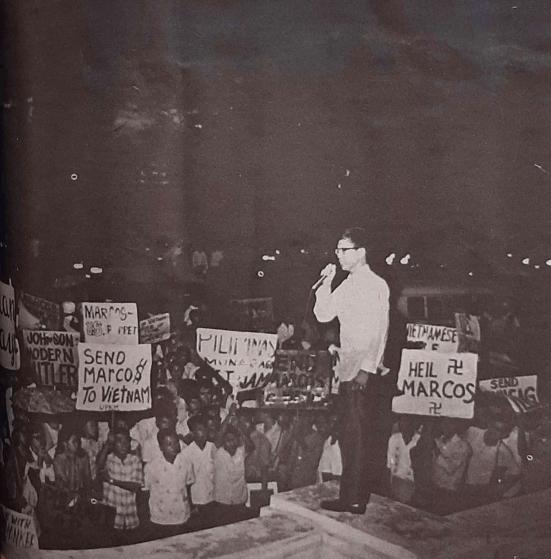

The MDP held an emergency meeting that morning and the perspective of the KM won over the majority. The umbrella group reached a compromise: they would hold simultaneous separate rallies — largely to save face over the reversal — and then converge on Plaza Miranda for “a People’s Congress.” An estimated fifty thousand participated, the largest attendance of any rally during the First Quarter Storm as subsequent events saw fewer and fewer people turn up.

The KM and the SDK were now clearly in the leadership of the storm, and the NUSP and NSL were not to be seen in the plaza. Their rivalry was rapidly disappearing, but the KM was under direct instructions from the CPP and the SDK was not. At the first People’s Congress and at subsequent rallies throughout the storm, the KM sought to provoke the crowd to violence, while SDK sought to calm it. As the SDK continued its rectification process and as the CPP recruited its leadership to its ranks, this tactical division gradually disappeared and by the opening of 1971 the two organizations proceeded in lockstep in response to the instructions of party leadership.

A speech delivered by the KM’s Nonie Villanueva, full of irreverent profanity, established the tone which would dominate the rostrums of the storm going forward, with putang ina and hindot standing in for political analysis and program.

Lacaba recounted that “[e]ach time a small group right in front of the speakers got up calling for a march to Malacañang, other demonstrators surrounding the group — suspected to be one led by an LP hatchetman — persuaded or ordered them to sit down.” It is significant that the “hatchetmen” of the Liberal Party were known to be present at the First Quarter Storm rallies and were suspected of attempting to instigate violent protest. The fact that Lopez and the LP benefited from these rallies was a poorly kept secret. To calm the crowd, the SDK repeatedly led them in the singing of the national anthem as a means of defusing tension. As the rally drew to a close, they sung the national anthem one last time and then announced that the MDP would be holding a meeting on Valentine’s day at Vinzons Hall, UP.

Ang Bayan hailed the February 12 demonstration, which it claimed one hundred thousand people had attended. They blamed the PKP for negotiating with Marcos to call off the protests, asserting that the “Lava revisionist renegades took the initiative of peddling through the MPKP spokesman as early as February 4 the erroneous line that ‘Marcos is only a small, although significant part’ of ‘the neocolonial-bourgeois political system’ (whatever that means) and to complain about a ‘purely anti-Marcos line.’” Using this language the MPKP had sought to call off the protests, and according to Ang Bayan, a BRPF statement declared that dialogues with Marcos could be used to “further intensify the national democratic struggle,” while an MPKP press release “announced that they were in a quandary whether or not to join the February 12 demonstration.” This defense of Marcos, Ang Bayan claimed was made in exchange for a set of promises from the President that “trade and cultural ties will be instituted with Eastern European countries immediately with the sending of officially accredited representatives. The possibility of securing loans or aid from said countries shall be explored.” Ang Bayan observed,

This is obviously the booty being dangled before the Lava revisionist running dogs of Soviet social-imperialism for their cooperation with the Marcos fascist puppet regime. … Relations with Soviet social-imperialism … will only add to the intensification of the exploitation of the Filipino people. The Soviet Union is no longer a socialist country; it has become capitalist, social-fascist and social-imperialist. Soviet social-imperialist “loans” and “aid” are no different from US imperialist “loans” and “aid”…

The CPP again insisted on its claim that dictatorship facilitated revolutionary struggle, openly expressing their hope that Marcos would suspend democratic processes: “How much nicer it would be if the US imperialists and reactionaries in the Philippines can no longer boast of their regular election! That would be a striking manifestation of how strong the revolutionary mass movement has become.”

The party, Ang Bayan claimed, had no responsibility for the emergence of “fascism,” stating “It is stupid to blame revolutionaries for the rise of fascism and the supposed possibility of a rightist coup.” The CPP rejected the revolutionary task of fighting against the rise of dictatorship, which can be waged neither by passive abstention nor anarchistic violence, both of which facilitate its emergence, but rather through the conscious organizing of the masses in an independent struggle for power. Thus, while the MPKP looked to defuse protests, the KM sought to provoke repression; both facilitated the declaration of martial law.

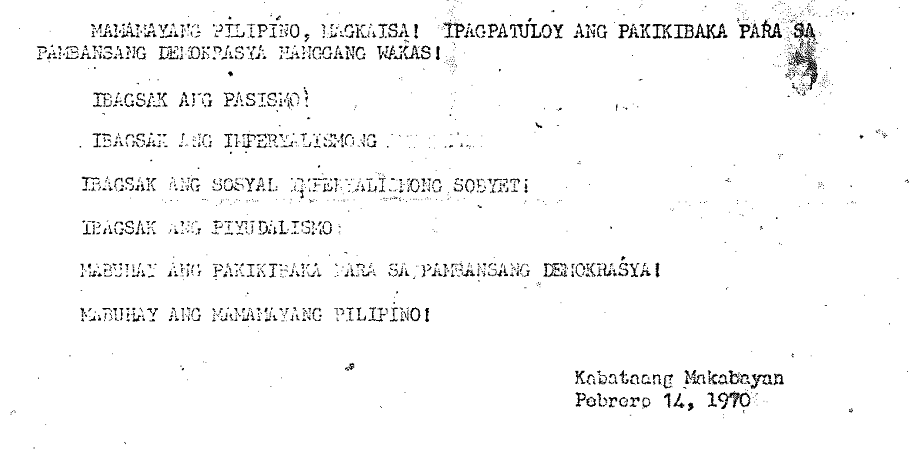

On February 14, fifty representatives from various student and labor organizations met to plan the next steps of the protest movement. They resolved that the February 18 rally, which had already been scheduled, would be a second people’s congress. The KM circulated a leaflet at the meeting calling for the “intensification of the struggle against the fascist puppet government of Marcos.” Following the political line of Ang Bayan, they denounced the “opportunist line” of the MPKP that “Marcos is a small but important part of the political system.” Countering that “the fascist puppet Marcos is the primary political agent of the native exploiting and oppressing classes and of American imperialism in our country,” they called for continued and strengthened anti-Marcos protests, and concluded by expanding the tripartite “Down with Fascism! Down with Imperialism! Down with Feudalism!” to include a final slogan: “Down with Soviet Social Imperialism!”

The remaining conservative layers of the MDP were being edged out and were looking to pull the umbrella group back from the clutches of the KM. On the same day that the majority of the organization agreed to hold a second people’s congress, the spokesperson of the MDP, Nelson Navarro, met with Justice Secretary Juan Ponce Enrile, at the Butterfly Restaurant where he was celebrating his forty-sixth birthday. Miriam Defensor and Violeta Calvo were both now employed in his office and they had arranged his meeting with the MDP spokesperson.

February 18: the Second People’s Congress

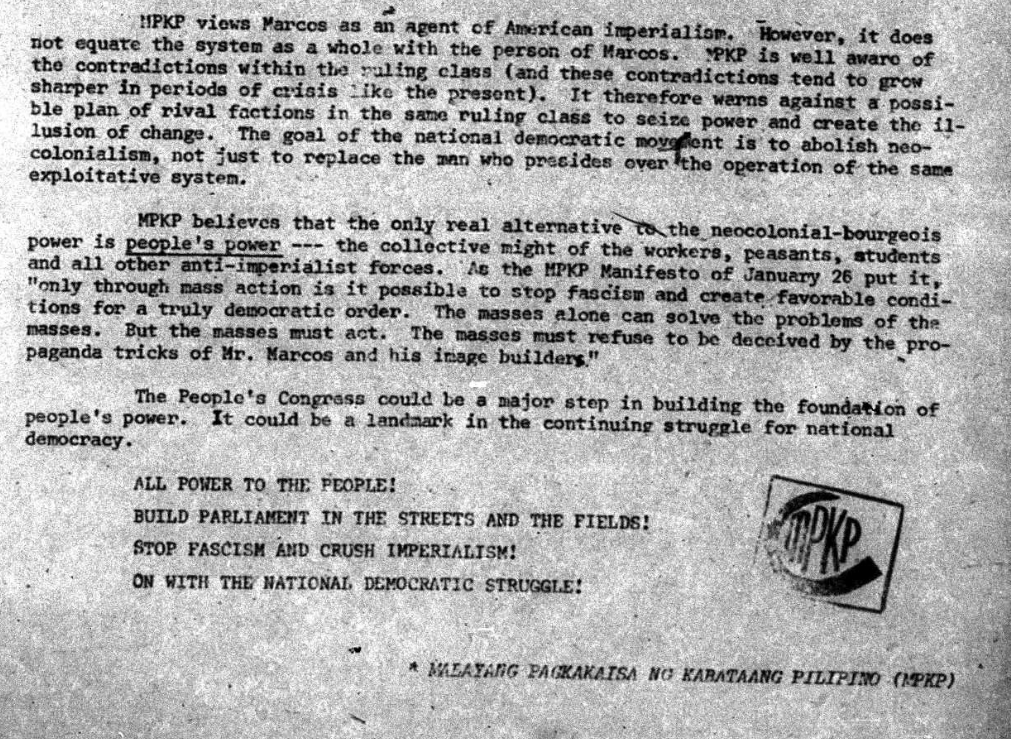

An estimated twenty thousand students — and “a sprinkling of workers and farmers” — assembled in Plaza Miranda on February 18 for the Second People’s Congress. The MPKP was reeling from the criticisms of the KM; they produced two leaflets for the demonstration, each written in a petulant and defensive tone. The first hailed the assembly as the development of their perspective of building “parliament in the streets,” and declared that

MPKP views Marcos as an agent of American Imperialism. However, it does not equate the system as a whole with the person of Marcos. MPKP is well aware of the contradictions within the ruling class (and these contradictions tend to grow sharper in periods of crisis like the present). It therefore warns against a possible plan of rival factions of the same ruling class to seize power and create the illusion of change. The goal of the national democratic movement is to abolish neo-colonialism, not just to replace the man who presides over the operation of the same exploitative system.

The MPKP stated that the “only real alternative … is people’s power — the collective might of the workers, peasants, students, and all other anti-imperialist forces,” mobilized to build “national democracy.”

The language of this leaflet expressed the dilemma of the MPKP during the First Quarter Storm. They could not endorse Marcos and would not endorse his bourgeois opponents. The only alternative was an independent fight of the working class leading the students and peasantry in opposition to the entire capitalist class, but the Stalinism of the PKP and its front organizations was intrinsically hostile to this perspective. The MPKP thus warned against both Marcos as well as the rival factions of the ruling class, while at the same time calling for a united front of “people’s power” with all “anti-imperialist forces” for national democracy. The MPKP unwaveringly insisted that a section of the national bourgeoisie was a component part of these progressive forces, and a necessary element of “people’s power,” yet they could not during the FQS publicly identify which section of the capitalist class was in their opinion progressive. This was precisely because their allegiances lay with Marcos and to say as much in early 1970 was political suicide.

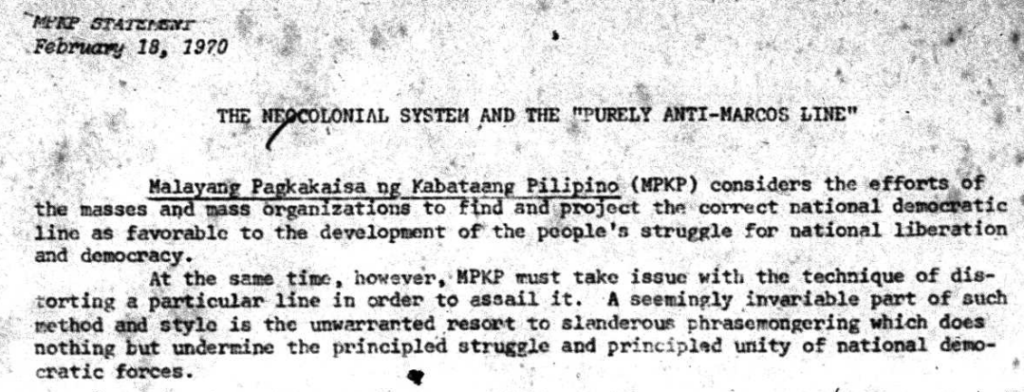

Later the same day the MPKP released a second leaflet defending themselves against charges made by the KM that they were diffusing anger against Marcos. They accused the KM of the “unwarranted resort to slanderous phrase-mongering” and distorting the MPKP political line. (One wonders what resort to “slanderous phrase-mongering” would be warranted.) Protesting overmuch, they stated,

MPKP never advocated shifting the people’s revolutionary actions against Marcos to “dissipated attacks” against various forces. MPKP did not exculpate the blood debts of Marcos by branding the revolutionary actions of the youth as a purely anti-Marcos line. MPKP has not fallen for the Marcos “nationalist” line at all, and it does not becloud the issue of puppetry and fascism of the Marcos regime. MPKP is not disarmed by the rhetorics [sic] of Marcos. MPKP does not underestimate the role of Marcos in the neocolonial-bourgeois system. MPKP does not consider Marcos as only a “victim”of this system.

The demonstrators marched to the Embassy, despite attempts by some of the organizers of the event to prevent them from doing so. Gary Olivar of the SDK told the crowd that there would be a rally at the Washington Day Ball at the Embassy on Saturday the twenty-first and that they should wait to demonstrate at the Embassy then. He led the crowd in repeated renditions of the national anthem in an attempt to defuse the mounting anger of the demonstrators.

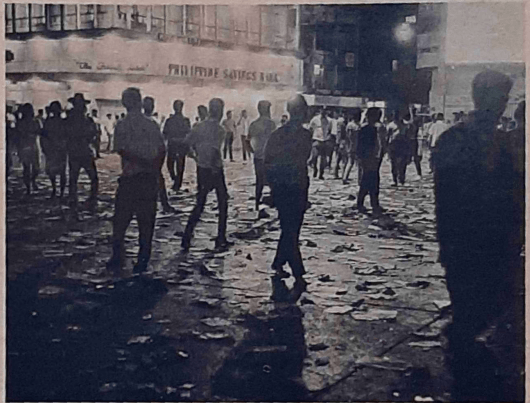

While the SDK was carefully attempting to limit the protests and prevent violence the KM was seeking to provoke it. Ang Bayan celebrated how the demonstrators “brilliantly” feinted to Malacañang, “completely outwitted practically all the fascist brutes” who deployed to the presidential palace, and then marched on the Embassy. At nine thirty at night, violence erupted at the Embassy.

Nelson Navarro, spokesperson for the MDP, stated that the organization peacefully finished its rally, and “the events that transpired afterwards it was unable to prevent or control,” as demonstrating students broke into the Embassy compound with “sticks, stones and homemade bombs.” Ang Bayan hailed the demonstrators who left the Embassy and “broke up into several groups and attacked such alien establishments as Caltex, Esso, Philamlife and other imperialist enterprises. They carefully avoided doing harm to petty bourgeois and middle bourgeois establishments.”

February 21: Devaluation

The economic crisis continued to worsen, and on February 21, upon the insistence of the IMF, Marcos devalued the peso and adopted the floating rate. The peso declined from $1:P4 to $1:5.90, falling 47.5% almost overnight. Gradually the conception emerged that the collapse of the peso had been the product of Marcos’ profligate election spending.

[Marcos] it is generally concluded, so debauched the Philippine peso — he is said to have spent no less than 800 million during his campaign — that the Government could not but devalue under the pressure of the International Monetary Fund, thus aggravating further the widespread poverty that characterizes Philippine society.

As a result of the IMF-imposed “floating-rate”, the prices of all prime commodities soared by nearly 40 per cent while wages inched up by 10-15 per cent … In an attempt to give the people the impression that his government is not powerless to halt spiraling costs, Marcos created in mid-1970 a Price Control Council which proved to be more than ready to grant official approval to price increases, especially when these were “requested” by American oil companies.

Rodrigo writes

The devaluation slowed the economy and stoked even more the public discontent. The peso wobbled further to $1:P6.50 in 1971. As a result of the rise in the cost of imports, the Philippine economy slowed to a crawl. GNP growth dropped to 2.74%, the worst level since 1960 and the second worst since 1946. Public discontent, already high, soared even further. Inflation rose to 15%, compared to the average of 4.5% in previous years. By 1971, nearly half the population were not earning enough to buy their minimum food needs.

As late as December 9 1969, in a speech at the Asian Institute of Management Marcos had declared, in the presence of Eugenio Lopez, that he would not devalue the peso. “The devaluation’s impact on Meralco was direct and considerable. Meralco got many dollar denominated loans during 1962-70. Its old financial projections were now obsolete and unless rates were hiked, the company was in danger of defaulting on some loans.” Tensions between Marcos and Lopez persisted and deepened.

February 26: Sunken Garden and the Raid on PCC

The MDP called off its promised Washington Day demonstration at the last moment but the front groups of the PKP it seems did not receive notification of the cancellation. Approximately fifty demonstrators, all associated with the PKP showed up in front of the embassy, which was surrounded by nearly one thousand police officers. The attention of the MDP was turned to the staging of a “Third People’s Congress” at Plaza Miranda on February 26.

Manila Mayor Villegas announced on the twenty-third that he would not grant a permit for a rally at Plaza Miranda, but would issue one for the use of the Sunken Gardens instead. The Sunken Gardens were part of the old moat outside the southern walls of Intramuros, and now served as a hazard in the nine hole municipal golf course circling the ancient city bulwarks. While it was but a stroll away from Agrifina Circle and Congress, it was nonetheless isolated and, from the perspective of law-enforcement, easily controlled.

On February 24, in a meeting of the MDP leadership at UP, spokesperson Nelson Navarro announced that the MDP would appeal Villegas decision before the Supreme Court. The appeal was filed by E. Voltaire Garcia, now employed in the offices of Senator Salvador Laurel, the next day. On February 26, at four in the afternoon on the day of the rally, the court upheld Villegas denial of a permit for a gathering in Miranda by a vote 8-2. The forces of the MDP gathered outside Plaza Miranda, waiting for the Supreme Court ruling, and there was a tense stand-off as they were blocked by anti-riot police “in full combat gear” from entering. On word of the decision, they moved to the Sunken Gardens. From the rally at the Sunken Garden the MDP proceeded to the Embassy.

Late that night — at two-thirty in the morning on February 27 — the Manila Police Department (MPD) raided the Philippine College of Commerce (PCC) [later PUP] with a warrant issued by Judge Hilarion Jarencio, arresting thirty-nine people, including Teodosio Lansang, and claiming to have confiscated several weapons.