What follows is the third post in an ongoing series on the fiftieth anniversary of the explosion of protests and police violence that marked the first three months of 1970 and which became known as the First Quarter Storm. For further details and citations please consult my dissertation, Crisis of Revolutionary Leadership.

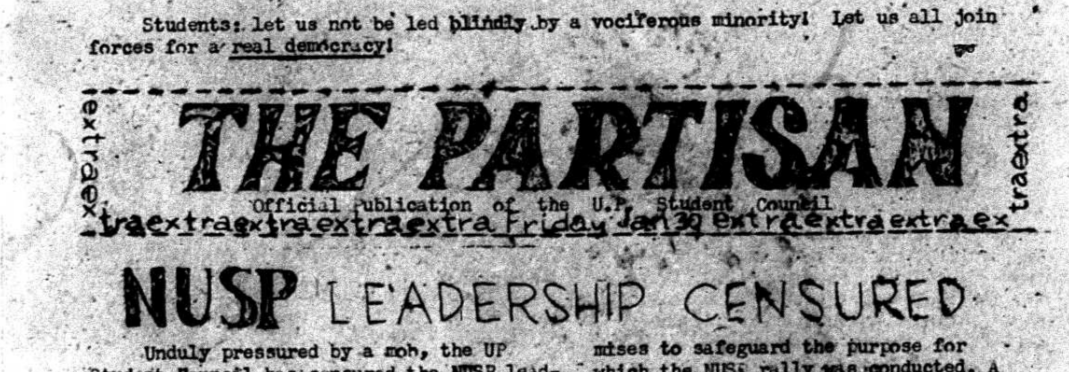

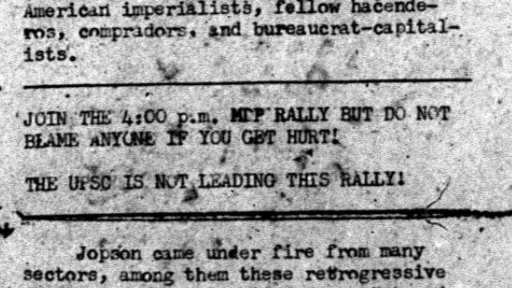

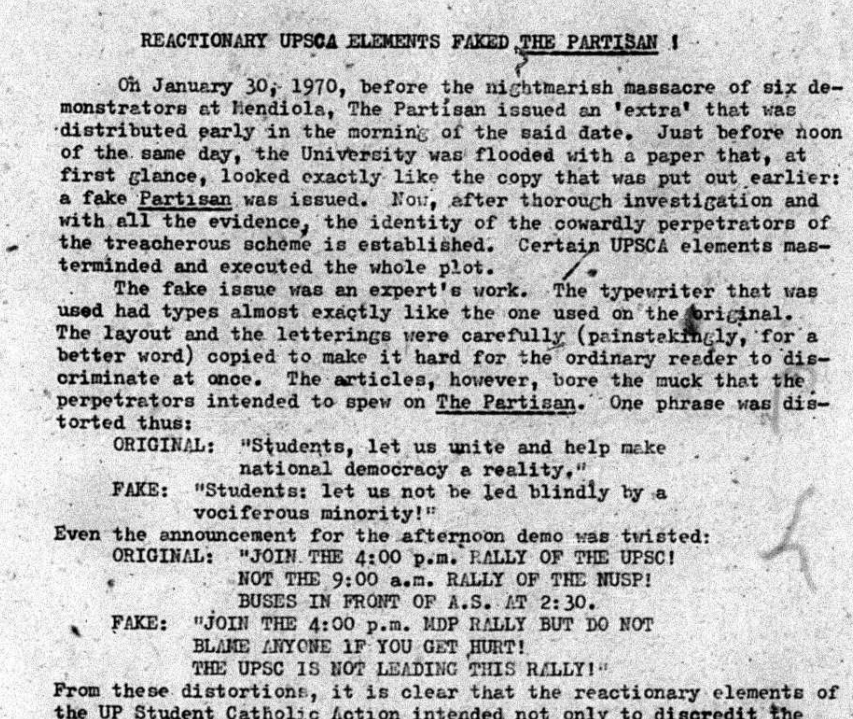

The demonstrators regrouped on January 30, a split emerging in their ranks. The majority, shocked by the violence of the twenty-sixth, rallied in front of Congress behind the banners of the KM and SDK denouncing the “fascism” of Marcos; the moderate student groups, clinging to the theme of a non-partisan convention, sent a delegation to meet with the president at Malacañang. Tensions were high. Ang Bayan declared that the January 26 protest “was merely the opening salvo for bigger mass actions of the near future. It is a blow against the reactionaries to be followed by more and bigger blows.” On the morning of the thirtieth, UP Student Catholic Action (UPSCA) circulated forged leaflets purporting to be from the UP Student Council, claiming that the demonstration did not have the sanction of the Council and warning students, “Don’t blame anyone if you get hurt!”

Finding that neither camp expressed its interests, and unable to articulate an independent position, the MPKP tagged along to the KM and SDK rally. They circulated a leaflet grossly incongruous with the mood of the assembled masses, calling for a partisan constitutional convention. The MPKP, they wrote, “did not and does not support the slogan of ‘non-partisan constitutional convention.’ … [This slogan] is deliberately designed to create illusion [sic] about the convention and to conceal the truth that the convention, whether openly partisan or not, will reflect the bankruptcy of the present political system.” The leaflet continued,

We must therefore rally the masses in a relentless struggle against neo-colonialism. The election of delegates and the convention itself may, however, be good opportunities to accomplish this principal task; but this could only be accomplished if we dispel all illusions in the minds of the masses …

MPKP calls for a People’s Constitution that will declare illegal and obsolete the power of imperialism, feudalism and capitalism, and project the concept of people’s power. The People’s Constitution should be a rallying program of the struggle for national democracy.

By rejecting the call for a non-partisan constitutional convention, the MPKP kept voting open to the two major political parties, while with its demand for a People’s Constitution it promoted the idea that by voting for delegates — including representatives from the Liberal Party (LP) and Nacionalista Party (NP) — the ‘people’ could secure representatives who would by legislative fiat make imperialism, feudalism and capitalism illegal. The reformist illusions which the MPKP were attempting to promote are staggering. As Marcos’ forces trained their guns on the protesters and fired, the MPKP activists had this leaflet in their hands. It made no mention — none — of the violence of January 26, and it claimed that the central task was to elect representatives to the constitutional convention who would simply declare capitalism illegal. The events of January 30 and the public outcry that they produced, compelled the MPKP to begin speaking of “fascism” while attempting to deflect the focus of public ire away from Marcos.

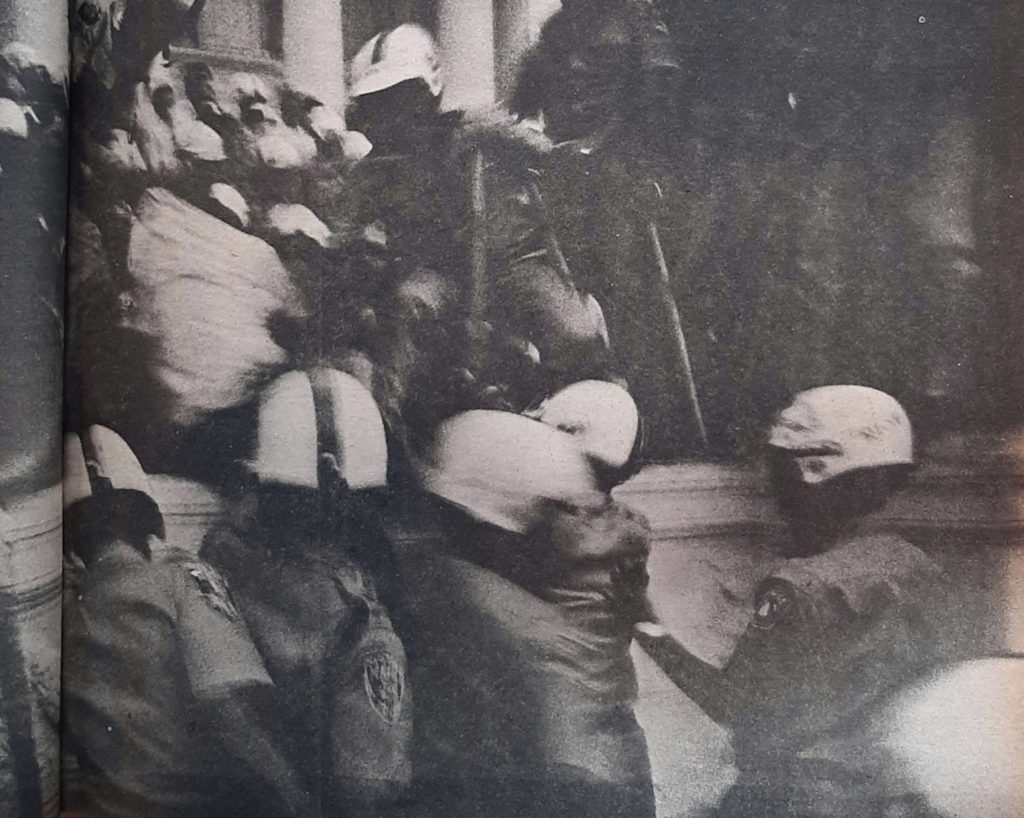

In the afternoon, Edgar Jopson, Portia Ilagan and others of the NSL and NUSP held a meeting with Marcos. Jopson demanded that Marcos put his commitment not to run for another presidential term in writing, and Marcos, irritated by Jopson’s demand, famously denounced him as the mere “son of a grocer.” As they were leaving, at shortly after six in the evening, violence broke out at the entrance to the presidential palace. The demonstrators had moved from Congress to Malacañang and as Marcos emerged from his meeting with Jopson they had gathered at Gate Four. Col. Fabian Ver and Major Fidel Ramos were “waiting for the President to give the order to shoot and the President did order: ‘Shoot them with water and tear gas.’”

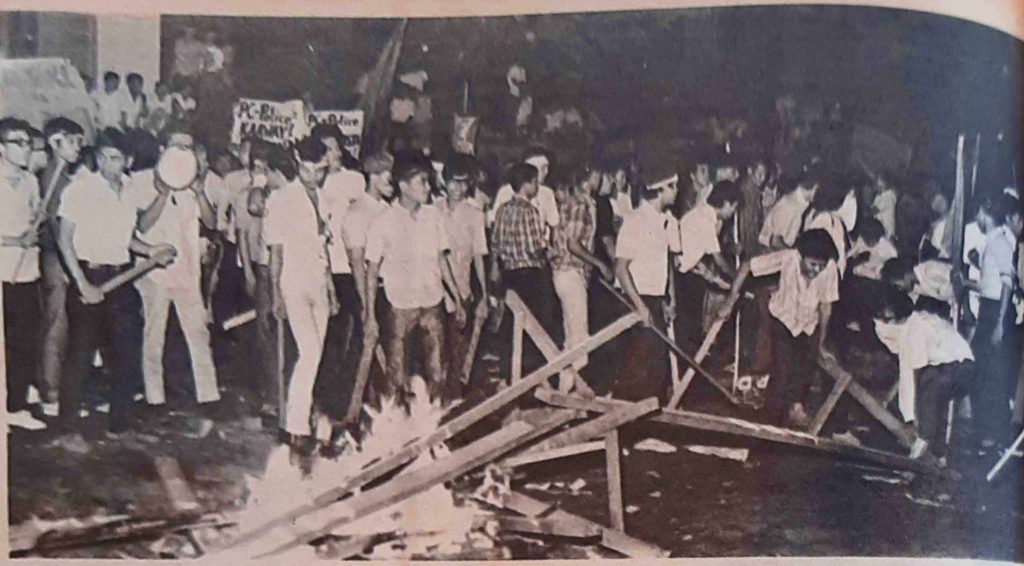

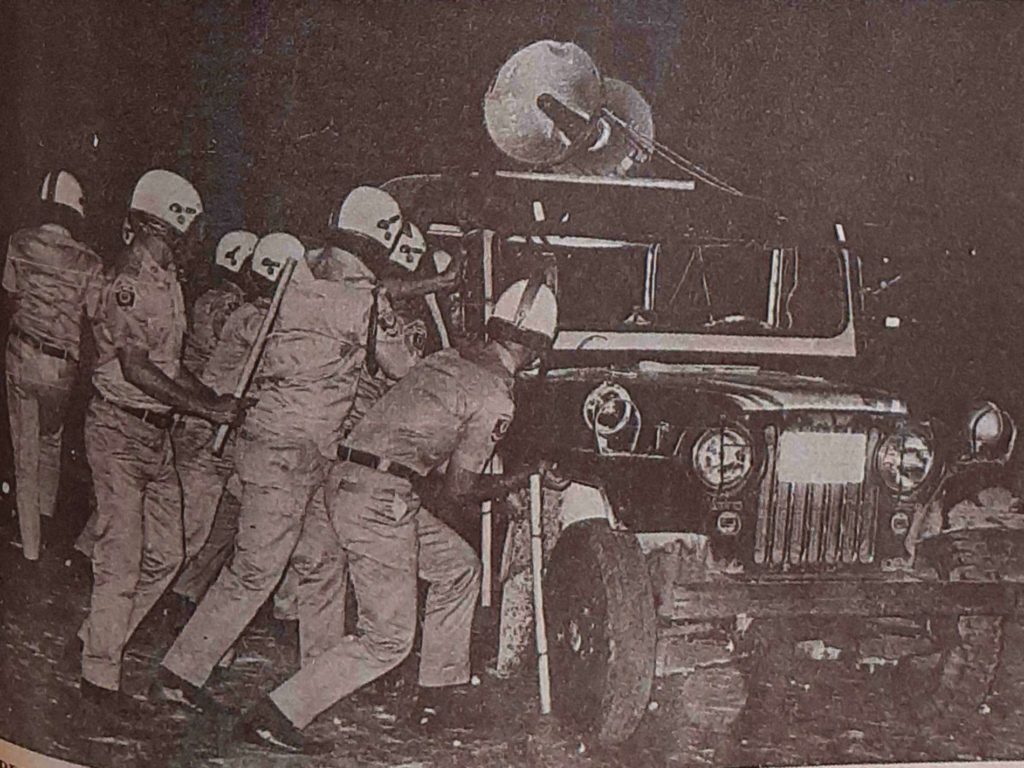

As security forces launched their assault, Gary Olivar issued instructions to the protesters by means of an ABS-CBN soundtruck, which Eugenio Lopez had apparently supplied to the protesters. Olivar used the vehicle to direct the ensuing Battle of Mendiola. A firetruck arrived to blast the protesters with water, but members of the SDKM (Mendiola) commandeered the vehicle, which they crashed through the palace gates. A series of explosions followed and the protesters retreated, constructing barricades on Mendiola bridge as they fell back from Malacañang. They briefly held this position and then fell back again.

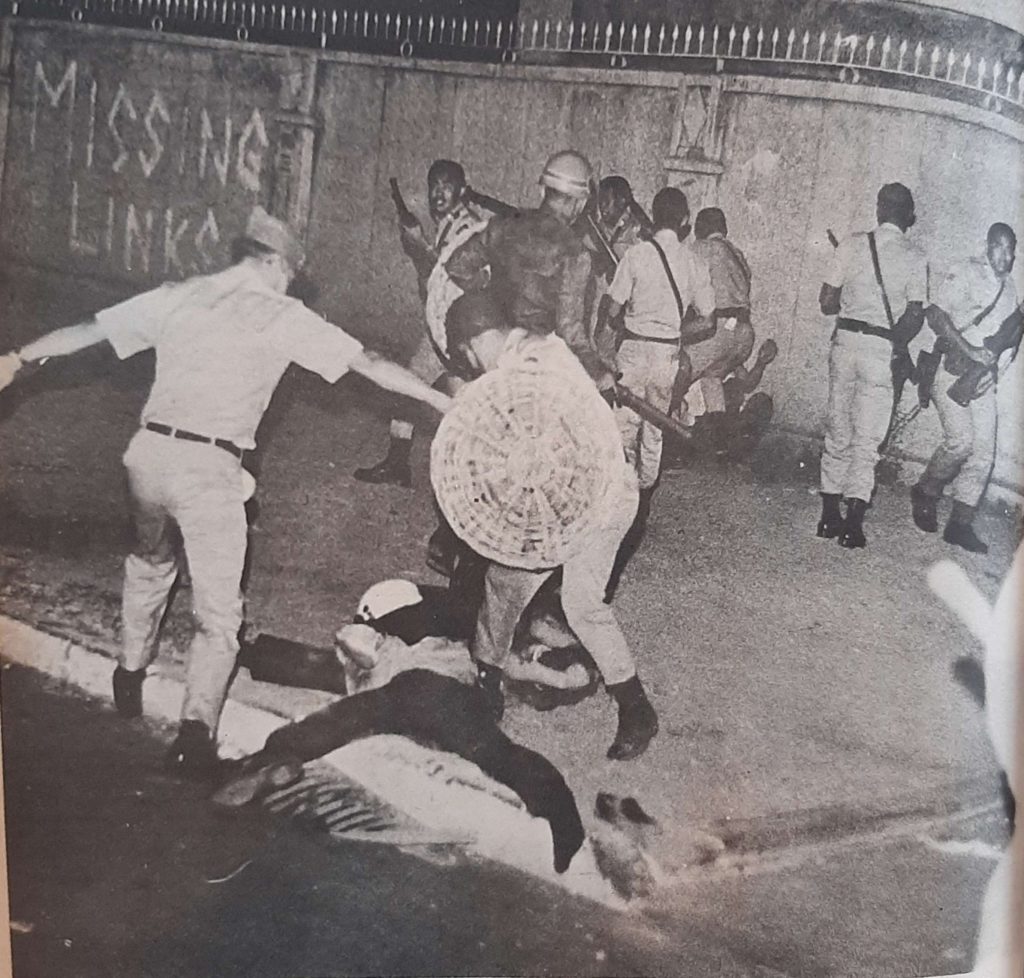

For several hours police and protesters waged a battle for the bridge. The police and military repeatedly fired on the student protesters, who responded with pillboxes, molotov cocktails and rocks, setting fire to vehicles in the street to slow the passage of the military. The barricades on Mendiola fell at around midnight. “There was nonstop hail of bullets, deafening gunfire as we scrambled on the sidewalk on the left side of Recto Avenue towards Lepanto and Morayta.” As they retreated the protesters overturned the concrete flower beds set up by Villegas along Recto, and some “abandoned vehicles were cannibalized, their tires turned into bonfires that gave off the pungent smell of burning rubber and the unmistakable look of an insurrection.”

Radio news reports initially announced that five or six protesters had been killed, but four were eventually named: Ricardo Alcantara, a student from UP; Fernando Catabay, MLQU; Bernardo Tausa, Mapa High School; and Felicisimo Singh Roldan, of UE. The dead ranged in age from sixteen to twenty-one; each had been shot by the police. One hundred seven students were injured on January 30, seventy-four of them from gunshot wounds, among them a boy from Roosevelt Academy in Cubao whose leg had to be amputated. Hundreds of students were arrested. They were detained in Camp Crame long past the legal maximum of six hours without charges. When protests were raised over the illegality of the mass detention, the PC charged the students with sedition, holding them for eighteen hours without food and then dismissing all charges for lack of evidence.

Marcos promoted the commander of the Metrocom, Colonel Ordoñez, who had directly overseen the assault on the students, to General on the spot. In 1972, the AFP admitted that a number of “government penetration agents” had participated in the “violent demonstration,” including Sgt. Elnora Estrada.