Fifty years ago this month an explosion of social protests and brutal police repression rocked the Philippines, launching a series of demonstrations and street battles that lasted from January to March. The events came to be known as the First Quarter Storm (FQS). What follows is the second in a series of articles examining the history of the events and ideas of the storm. Those interested in further details, or citations for the facts and quotations below, are encouraged to consult my dissertation, Crisis of Revolutionary Leadership.

January 26

As 1970 opened Ferdinand Marcos had just secured re-election, becoming the only President in Philippine history to do so. The election was likely the bloodiest and most corrupt the country had yet seen. Entire towns had been burned to the ground in a manner that was being compared in the press to the massacre carried out by American soldiers at My Lai, an event which had just come to public awareness. Sergio Osmeña Jr., the defeated rival candidate, famously remarked, “We were outgunned, outgooned, and outgold,” although it might be said, that it was not for want of trying.

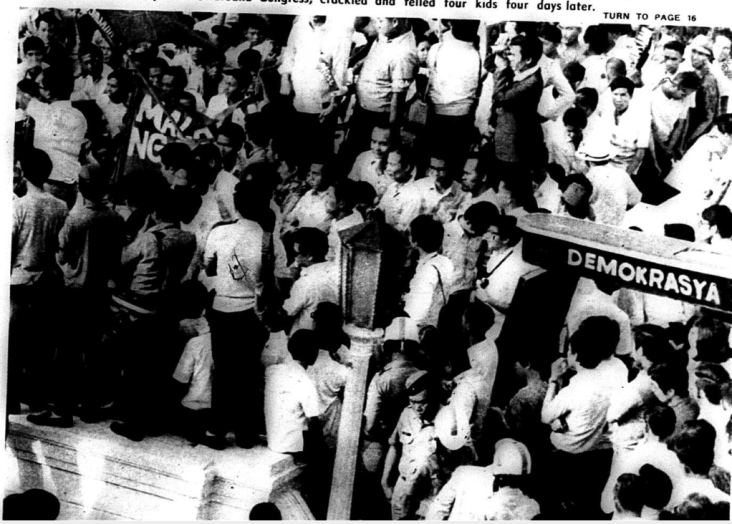

Monday, January 26, was the newly re-elected President’s State of the Nation Address. Anticipating unrest, Metrocom, the unit of the Philippine Constabulary operating in Metro Manila, made preparations to suppress it. Two organizations were granted permits to rally in front of Congress, the National Union of Students of the Philippines (NUSP) and Ang Magigiting [The Brave], the political vehicle of radio personality Roger Arienda, while the Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (PKP) youth organ, Malayang Pagkakaisa ng Kabataang Pilipino (MPKP), was able to secure a permit to stage a protest behind Congress. Neither of the youth organizations affiliated with the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), the Kabataang Makabayan (KM) and the Samahan ng Demokratikong Kabataan (SDK) were able to obtain a permit at all. As late as January 22, there was still discussion in these organizations as to how best to protest during the State of the Nation address. The University of the Philippines Student Council (UPSC) chaired by Jerry Barican of the SDK stated that it intended to demonstrate to “clarify its stand on the Constitutional Convention and to bid for public support.” They weighed holding a separate rally at Plaza Miranda, where, Tagamolila reported, the Kamanyang Players would perform, “reinforcing the issues with dance and drama.” This proposal wound up being rejected and the UPSC, KM and SDK all decided to join the NUSP rally in front of Congress.

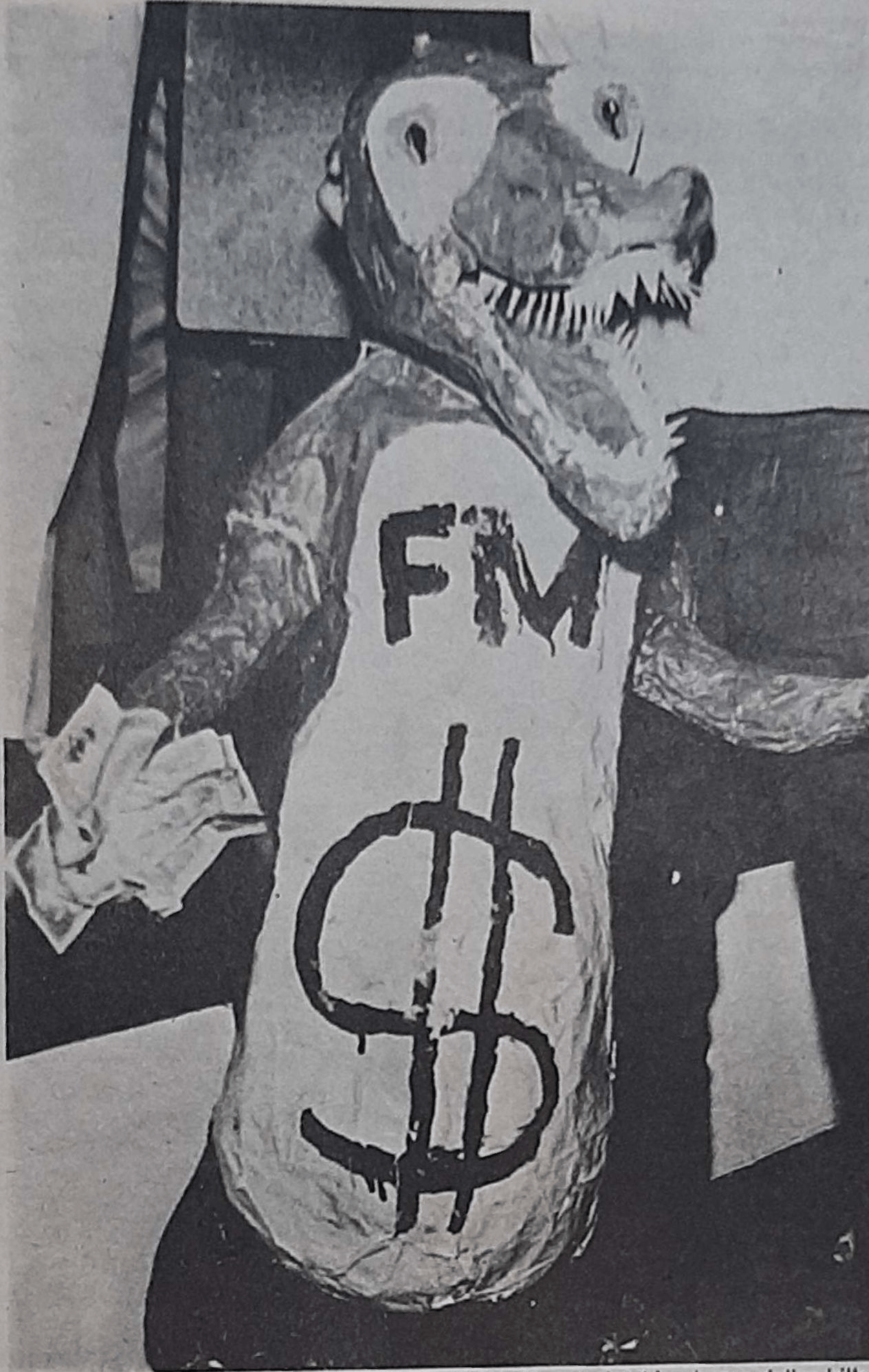

Opening the first session of the Seventh Congress, on Monday, January 26, Fr. Pacifico Ortiz — the president of Ateneo University — delivered an invocation. The country was standing, he intoned, “on the trembling edge of revolution.” Marcos delivered his State of the Nation speech, which he entitled “National Discipline: the Key to our Future.” Marcos had ordered speakers to be set up in front of Congress to broadcast his speech, overpowering the public address system of the protesters, whose “lone amplifier was … drowned out by four loudspeakers set up by the Army Signals Corps.” The protesters dispatched a representative who quickly met with Senator Aquino to request that Marcos’ speakers be taken down, but they were not removed. Newspapers estimated that forty thousand people rallied outside of the halls of Congress, while “the number of security forces mustered for the occasion was estimated at 7,000” Arienda’s group had brought a mock coffin which they said symbolized the death of democracy, while a separate group of demonstrators from UP carried a papier-mâché crocodile with a dollar sign on its belly and they set the crocodile on top of the coffin.

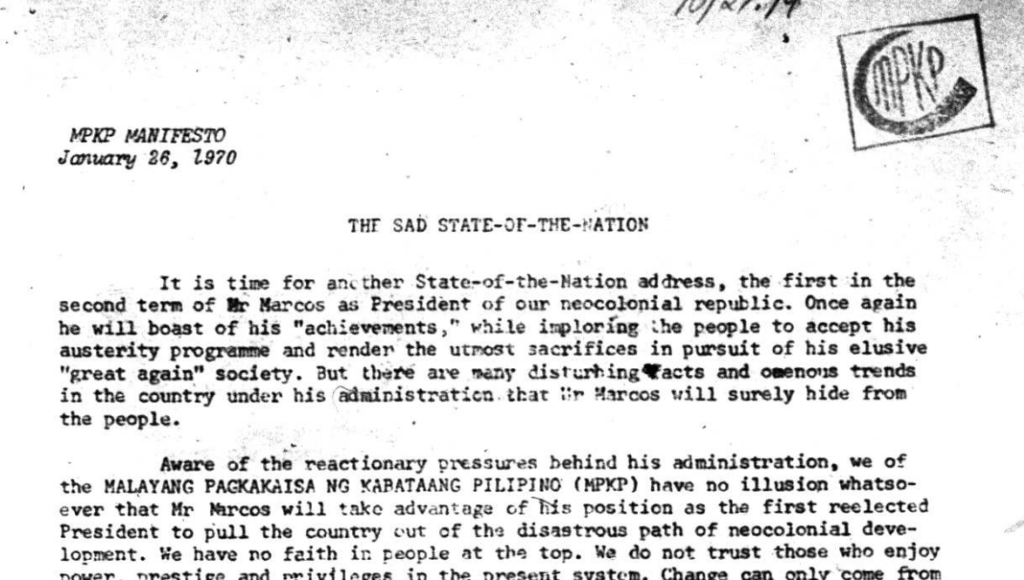

In a manner unintentionally symbolic of their increasing political isolation, the MPKP distributed their leaflet, The Sad State of the Nation, behind the house of Congress. The statement stressed that the organization had no illusion that “Mr. Marcos will take advantage of his position as the first reelected president to pull the country out of the disastrous path of neocolonial development … Change can only come from the people themselves, particularly those who are most oppressed.” The MPKP called for “a mighty wave of mass action to deal with the following problems: The Fascist Menace … ” In this section the MPKP charged the military with “recruiting student leaders to intelligence agencies and using them to infiltrate progressive youth organizations … to push these organizations along a disastrous adventurist line and to sow dissensions in the ranks of the genuine anti-imperialist groups. Just the other day they again circulated a slanderous leaflet against MPKP, charging it of subversion and denigrating its leaders.” While denouncing ‘fascism,’ the MPKP rooted this political danger not in capitalism, but in the KM and SDK who, infiltrated by the military, were pursuing a “disastrous adventurist line.” The other problems which mass action needed to solve were “Economic Sabotage” on behalf of US imperialism; “Bogus land reform;” and the worsening economic conditions of the masses. They put forward no concrete program to solve any of these problems but simply issued a repeated call for mass action. Action to what end? This was never addressed. The MPKP’s call for mass action was subsumed under the slogan: “Build Parliament in the Streets!” Given the political line articulated by the MPKP it was logical to assume that mass action should be mobilized to pressure Marcos to “take advantage of his position.”

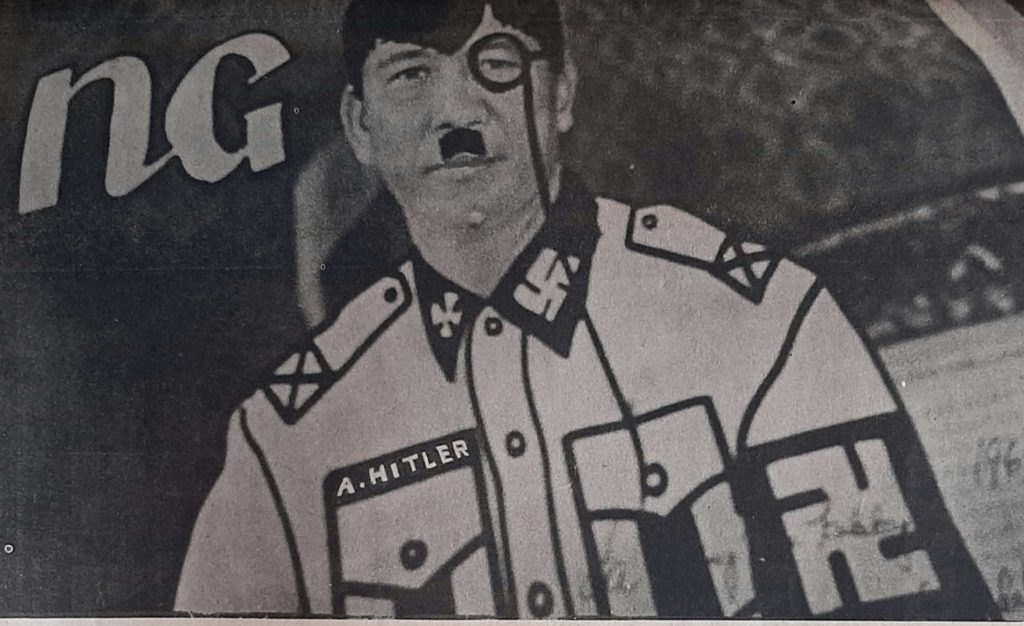

Arriving at four in the afternoon, just as Marcos was about to speak, “the KM members surged forward through the crowd in a diamond formation until they positioned themselves in the forefront of the demonstration site, their huge red streamer very noticeable and overshadowing all the other placards.” They distributed a “position paper” to the crowd entitled “A Neo-colony in Crisis” which began, “As the Seventh Congress of the Philippines opens today, the Kabataang Makabayan presents to the Filipino people the real state of the nation. In the interest of exposing to the people the conditions in the country so that they may act to change them, the KM joins today’s demonstration in unity with progressive and national democratic organizations and individuals.” The “reactionary Marcos administration,” they stated, “has strengthened and deepened its commitments to the neo-colonial schemes of the imperialist United States and Japan and social-imperialist Soviet Union in Asia.” The KM denounced Marcos’ “plan to open trade relations with pseudo-socialist countries, specifically the Soviet Union.” Marcos’ plan was “in consonance with the US-Soviet policy of dividing the world between themselves. … the Soviet Union has been transformed into a neo-capitalist state that exploits and oppresses not only the Soviet people but also the peoples of its colonies in the same fashion as the United States does.” The KM repeated Sison’s recent denunciation of the Constitutional Convention, and warned that “resurging fascism … emphatically characterizes the Marcos administration.” This was evidenced by violence against “the people” carried out by “Hitler-worshippers in the reactionary armed forces.” The KM drew this conclusion:

But one thing is sure. As the ruling class can not rule anymore in the old way, more violent repressions are bound to unfold. Yet, it is a truism that in any society, as the ruling class becomes more violent, the resistance of the oppressed is increased tenfold. The revolutionary movement emerges to destroy the inequities of the old order.

This was the standard line of the CPP: fascism and repression only cause the revolutionary movement to grow.

An array of speakers addressed the crowd, struggling to be heard over Marcos. When Luis Taruc was given the microphone the demonstrators loudly booed him and shouted, “We want Dante!,” referring to Bernabe Buscayno, Kumander Dante, head of the New People’s Army (NPA). Lacaba reported that “There were two mikes, taped together; and this may sound frivolous, but I think the mikes were the immediate cause of the trouble that ensued. … Now, at about half past five, Jopson, who was in polo barong and sported a red armband with the inscription “J26M,” announced that the next speaker would be Gary Olivar of the SDK.” Jopson then hesitated, reluctant to give the mic to Olivar. He led the crowd in singing the national anthem. When the singing finished, he continued to clutch the microphones, and then announced that the NUSP rally was over and called on students to disperse. “It was at this point that one of the militants grabbed the mikes from Jopson,” and passed them to “a labor union leader” — most likely Rodolfo del Rosario. He “attacked the ‘counter-revolutionaries who want to end this demonstration,’ going on from there to attack fascists and imperialists in general. By the time he was through his audience had a new, a more insistent chant: ‘Rebolusyon! Rebolusyon! Rebolusyon!’”

Marcos emerged from Congress. “No less than Col. Fabian Ver, chief of the presidential security force, and Col. James Barbers, Manila deputy chief of police [and Joma Sison’s maternal uncle], personally led the heavy escort. Brig. Gen. Hans Menzi, [publisher of the Manila Bulletin] the inseparable chief presidential aide, trotted behind.” The protesters set Marcos’ effigy on fire, hurling the crocodile and coffin at his entourage; the police charged the protesters and “flailed away, the demonstrators scattered.” The President and his wife safely drove away. The protesters quickly regrouped and began throwing rocks and soft-drink bottles at the police, who arrested some of the demonstrators on the spot. Rotea wrote that “[t]hey continued hitting demonstrators they had just caught even if they were not resisting at all, or were pleading for mercy, or were already down.” The police violence was indiscriminate and a number of reporters were beaten alongside the demonstrators. The police then “retreated into Congress with hostages. The demonstrators re-occupied the area they had vacated in their panic. The majority of NUSP members must have been safe in their buses by then, on their way home, but the militants were still in possession of the mikes.”

About two thousand demonstrators remained in front of Congress. They began chanting “Makibaka! Huwag matakot!” and then sang the Internationale. Senator, and former Vice President, Emmanuel Pelaez emerged from the Congressional building to address the crowd and the SDK supplied him the microphone. The crowd chanted for the arrested protesters being held inside by the police to be released, but the KM and SDK leaders silenced the crowd so that Pelaez could speak. Pelaez made a lengthy speech in an attempt to calm the crowd, while the police regrouped, moving around to the north side of the building. As Pelaez completed his speech, they charged the demonstrators. Lacaba recounted that

The demonstrators fled in all directions … Three cops cornered one demonstrator against a traffic sign and clubbed him until the signpost gave way and fell with a crash. … The demonstrators who had fled regrouped, on the Luneta side of Congress, and with holler and whoop, they charged. The cops slowly retreated before this surging mass, then ran, ran for their lives, pursued by rage, rocks and burning placard handles. … In the next two hours, the pattern of battle would be set. The cops would charge, the demonstrators would retreat; the demonstrators would regroup and come forward again, the coups would back off to their former position. … There were about seven waves of attack and retreat by both sides, each attack preceded by a tense noisy lull, during which there would be sporadic stoning, by both cops and demonstrators.

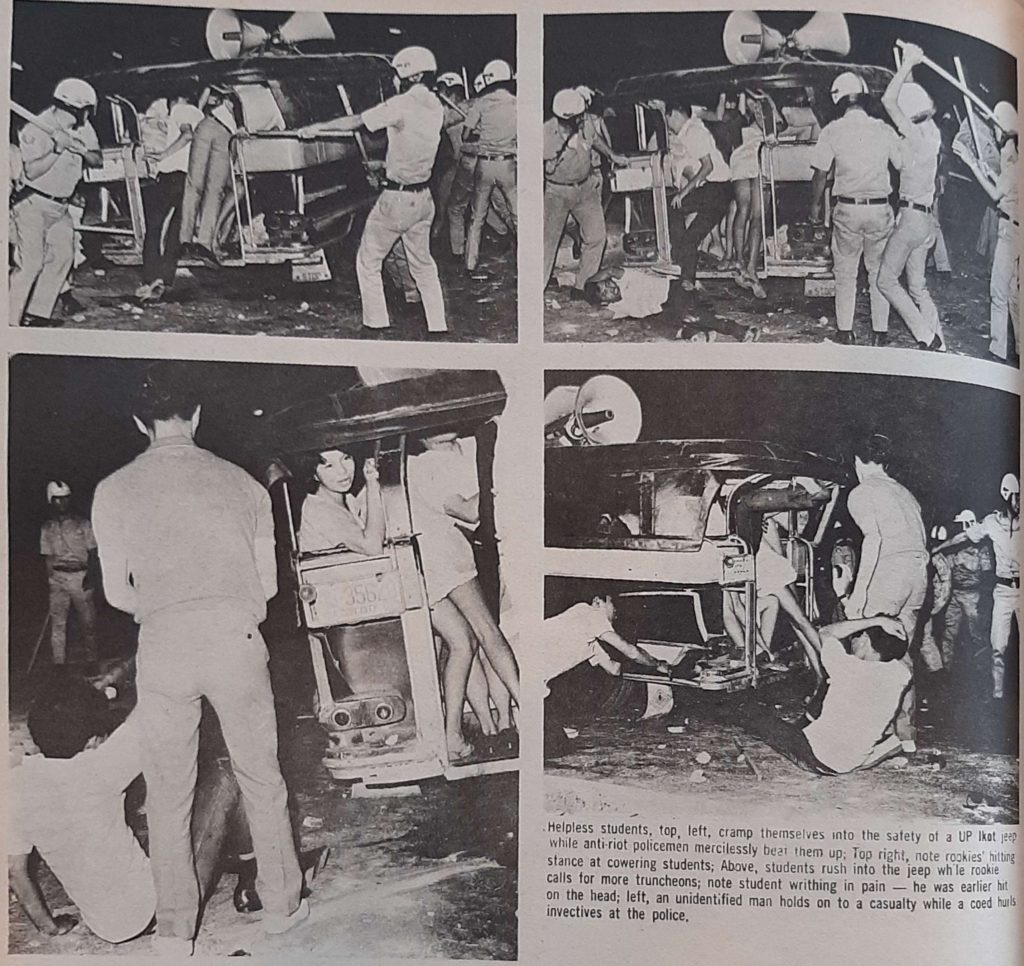

The demonstrators had hired a jeepney and some crowded into it for shelter. The police “swooped down on the jeepney with their rattan sticks, striking out at the students who surrounded it until they fled, then venting their rage some more on those inside the jeepney who could not get out to run. The shrill screams of women inside the jeepney rent the air. The driver, bloody all over, managed to stagger out; the cops quickly grabbed him.” The police began firing shots in the air and the demonstrators fled.

By eight in the evening, less than two hours after it had started, the battle in front of Congress had ended. Among those injured were members of both the NUSP and the KM. Rotea reported that “initial official reports showed that about 300 youths were injured while 72 law enforcers were wounded in the Congress riot.” A great many demonstrators were arrested — “thrown into and packed like sardines at the city detention jail.” Salvador Laurel and John Osmeña, along with a handful of other politicians, “personally spent the night there and helped expedite their release.” Of those arrested, nineteen were charged but were released without bail.

Aftermath

The next three days saw a relentless stream of recriminations and posturing with regard to the violence of January 26. Nemesio Prudente, President of the PCC, who had been beaten by the police alongside students, told the press, “I will support a nationwide revolutionary movement of students to protest the brutalities of the state.” James Barbers, Deputy Chief of the MPD, who had for years received the support of the KM, issued a statement that “We maintain that the police acted swiftly at a particular time when the life of the President of the Republic — and that of the First Lady — was being endangered by the vicious and unscrupulous elements among the student demonstrators. One can just imagine what would have resulted had something happened to the First Lady!” Mayor Villegas defended “the police action and said they acted on his orders to protect the President.” Edgar Jopson published a statement washing his hands of the event, claiming that the riot started when he attempted to end the demonstration. Ruben Torres, chair of the MPKP, issued a brief statement, which concluded, “Police brutality, blatantly displayed in the January 26th demonstration will not dampen the surging activism of the youth. All the more, this even increases the enthusiasm and determination of the youth in their struggle for national democracy.” The Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation (BRPF), which, like the MPKP, was allied to the PKP, issued a similar statement denouncing the “the use of naked force” by “the power holders.” Neither the MPKP nor the BRPF mentioned Marcos at all, for he was their political ally.

Marcos released a press statement regarding the events.

Reports received by me on the demonstration tend to show that the students were not responsible for the riot that ensued during the demonstration.

I accept the veracity of these reports and I accept the statement of responsible student leaders present at the demonstration that they were not responsible for the riots.

Initial reports from police and intelligence indicate that the riot was instigated by non-student provocateurs who had infiltrated the ranks of the legitimate demonstrators. This is being investigated.

Marcos was looking to blame the riots on the CPP — whom he labeled provocateurs infiltrating the ranks of the demonstrators — yet he was well aware that part of the responsibility for the riot rested with police agent provocateurs who had infiltrated the ranks of the students, a number of whom played leading roles in the January 26 events and in the subsequent development of the FQS. Lacaba related how a young woman denounced the police during the riot — “Those sons of bitches, their day is coming. [Putangna nila, me araw din sila.]” She was Elnora ‘Babette’ Estrada, a member of the National Council of the KM, and an undercover police agent with the rank of sergeant.

On Tuesday, the day after the violence, Jerry Barican announced that students at UP would be staging a week-long boycott of classes to express the students’ “vehement denunciation of police brutality and of other terroristic means being perpetrated by the Marcos administration.” Student leaders held a meeting at Far Eastern University (FEU) where they resolved to stage a demonstration on January 30.

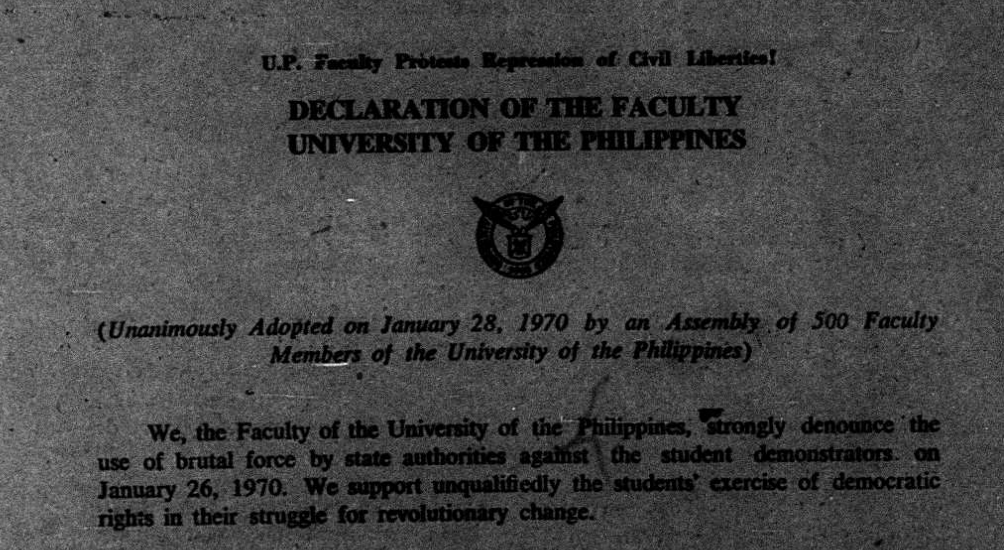

On Wednesday, January 28, the KM issued a leaflet in which they claimed that the “students dramatically exposed to the people the deteriorating conditions in the country” and called for the continuation of the “anti-fascist” struggle. A Senate and House joint committee, chaired by Lorenzo Tañada, was formed to investigate the “root causes of demonstrations in general.” Five hundred UP Faculty members gathered on the same day and drafted a declaration, adopted unanimously, which stated that they

strongly denounce the use of brutal force by state authorities against student demonstrators on January 26 1970 … We strongly urge that congressional and other investigations be so conducted and concluded as to reaffirm democratic principles … The Faculty holds the present administration accountable and responsible for the pattern of repression and the violation of rights. Open letter of UP faculty on January 28 denouncing the police brutality of the 26th.

On Thursday, January 29, the UP Faculty, including President Salvador Lopez, marched to Malacañang where they held a rally and then met with Marcos and presented him their declaration.

The events of the next day, January 30, would come to be known as the Battle of Mendiola, an explosion far larger, and more violently suppressed, than that of January 26. The First Quarter Storm had begun.