Fifty years ago this month an eruption of protests and violence — molotov cocktails and gunfire — in the streets of Manila, launched the heady, charged days of January to March 1970. The paroxysm that opened the decade came to be known as the First Quarter Storm (FQS), a period which began on January 26 as Marcos delivered his State of the Nation address and which ended in late March as final exams commenced, the semester drew to a close, and students returned to their homes for the summer.

Jose F. Lacaba, Days of Disquiet, Nights of Rage: The First Quarter Storm & Related Events (Pasig: Anvil Publishing, 2003). What follows is the first of a series dealing with the critical events of the First Quarter Storm, a revolutionary moment in Philippine history. This initial post deals with the political themes which emerged to give shape to the storm during the first rumbling signs of its onset. More detailed development of these ideas, as well as citations for the quotations and facts included here, can be found in my doctoral dissertation. I would encourage interested readers to find a copy of Jose Lacaba’s Days of Disquiet, Nights of Rage, a compilation of articles originally written for the Philippines Free Press, which stands preeminent among the firsthand accounts documenting the events of the FQS. The slim volume transcends reportage and embodies in its prose both the shock and anger of the storm and ranks among the better works of Philippine literature in English. Lacaba wrote of the FQS:

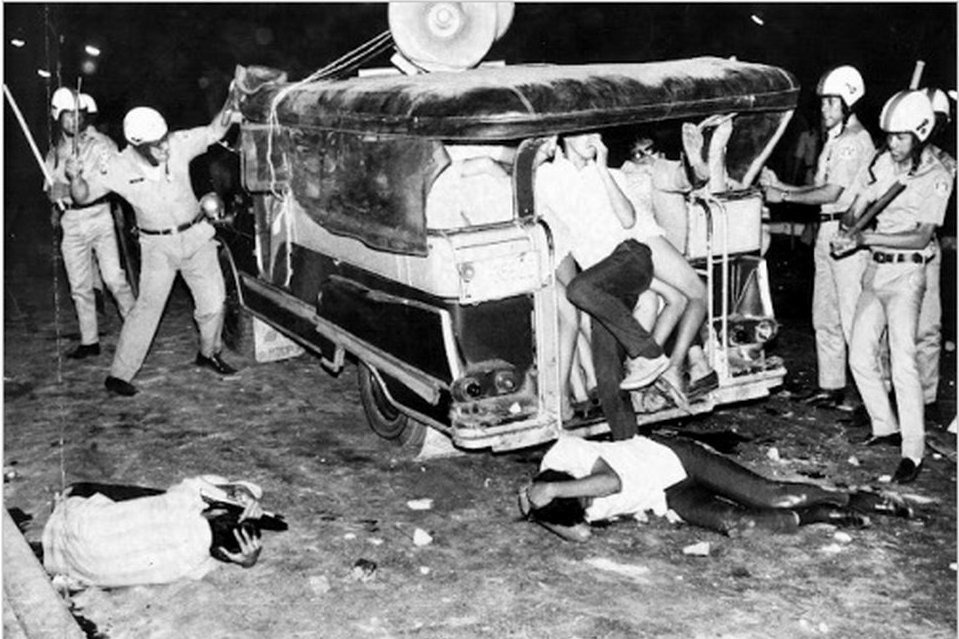

… the blood-spattered truncheons, the fires in the night, the staccato of Armalites, the thunder of home-made bombs, the tear gas crawling down streets and alleys, the flag carried with the red field up, the fists in the air, the tramp of tired but resolute feet, and most of all the faces of an awakened nation, the dusty, sweaty, exultant faces of militant young men and women on the march, signing the vivid air with their courage. It was a glorious time, a time of terror and of wrath, but also a time for hope. The signs of change were on the horizon. A powerful storm was sweeping the land, a storm whose inexorable advance no earthly force could stop, and the name of the storm was history.

The new decade dawned to protests and repression in the streets of Manila, and Marcos, who had been re-elected president in November 1969 at the end of a campaign marked by immense corruption and violence, readied the apparatus of martial law. In January 1970, in the thick of demonstrations, “Marcos sent a large military convoy racing north to the Mansion House in Baguio, filled with money, guns, ammunition and government papers in crates, to set up an alternative seat of government.” Amando Doronila, then writing for the Daily Mirror, “exposed a Department of Foreign Affairs circular asking all Philippine embassies and missions abroad to conduct research on cases where martial law had been imposed in other countries.” According to Rodrigo, Marcos wrote in his diary in 1970

“The disorders must now be induced into a crisis so that stricter measures can be taken … A little more destruction and vandalism, and I can do anything.” He also wrote: “we should allow the communists to gather strength, but not such strength that we cannot overcome them.” On February 12, 1970, he rued that a noisy student demo had ended peacefully: “I secretly hoped that the demonstration would attack the Palace so we could employ the total solution.” His end goal was plain: “I have that feeling of certainty that I will end up with dictatorial powers.”

As Marcos wound up the spiral spring of state repression, his rivals funded the protests; but when his leading opponents, the Lopez brothers, reached a temporary truce with Marcos in March, the FQS dissipated. The social anger of the masses marching in the streets was fueled by the skyrocketing prices of basic necessaries, massive social inequality and state repression in defense of it. They were organized, however, behind banners which denounced Marcos alone, citing his ‘puppetry’ and calling for his ouster. At no point did the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) or its front organizations, which came to play the leading role in the development of the storm, address the root of the social ills confronting the working class — capitalism.

From 1970 to 1972, in the midst of a devastating economic crisis which saw the price of basic goods move beyond the reach of the working class and peasantry, the CPP and its front organizations were in an alliance with leading representatives of the old landed oligarchy. The wealth of Lopez and Aquino was based in sugar, Laurel in coffee, and their sugar and coffee money provided financial and political support to the CPP. The Kabataang Makabayan (KM) and Samahan ng Demokratikong Kabataan (SDK), closely tied to the party, received favorable press coverage, television and radio slots to broadcast their ideas, and funding. Famed director and activist Behn Cervantes remarked, “Since this was the crest of the First Quarter Storm, it was relatively easy to get contributions [for the KM and SDK] from big business tycoons.” This funding did not create the unrest, which arose from an explosive outrage at the political and economic crisis, but it did assist those responsible for directing it behind a specific set of elite interests.

The CPP used its forces among the youth, peasantry and working class to direct protests and strikes exclusively against Marcos on behalf of their allies, channeling all of the immense social anger of the time behind the interests of a section of the ruling class. The CPP entered alliances with the right-wing Social Democrat (SocDem) forces, whose roots lay in the ouster of Sukarno and the genocide of the Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI) and whose political orientation in the Philippines was to agitating for a military coup. Thus, the CPP not only provided Marcos with a pretext for martial law, they disarmed the only genuine opposition to military rule. None of the ruling class allies of the CPP were opposed to martial law; many, including Aquino, favored it, but desired to be sitting in Malacañang when the curtain of dictatorship rung down. Successful opposition to dictatorship rested in securing the independence of the working class from the entirety of the bourgeoisie, with its coup plotting and assassination schemes and machinations toward military rule. The CPP, in keeping with its Stalinist program, labored to thwart this independence, working at every turn to subordinate the class struggle of workers to the interests of the bourgeoisie. That the explosion of massive anger from the working class, confronting crisis and near starvation, was directed behind the interests of the ruling class rivals of Marcos was almost entirely the work of the CPP.

Marcos, meanwhile, plotting the imposition of dictatorship and laying the blame for the vast social unrest at the feet of the CPP, was secretly allied to the CPP’s rival, the Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (PKP). The PKP, over the course of the next two years, assisted Marcos in his declaration of martial law, ghostwriting his justification for dictatorship and entering his cabinet. For all his denunciations of Communism, Marcos established his dictatorship with the complete support of one of the country’s two Stalinist parties.

A series of protests, held in front of Malacañang on January 7, 16 and 22, saw tensions mount in the lead-up to the State of Nation Address on the twenty-sixth. Over the first weeks of January, the language of the protests shifted from the Kabataang Makabayan’s (KM) initial rhetoric of “student reform” to the denunciation of Marcos as a “fascist.”

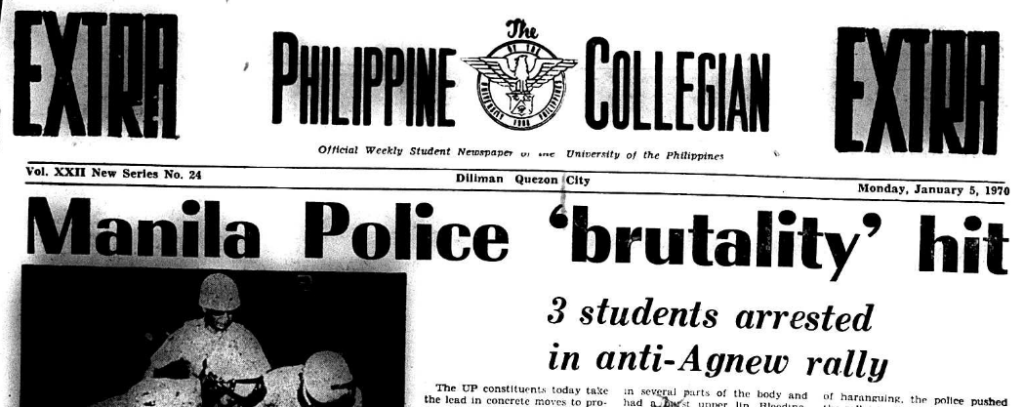

The KM and SDK launched the first demonstration of 1970 narrowly focused on the issue of student reform. They envisioned protests proceeding along similar lines to those of early 1969, which had been marked by a series of university strikes demanding campus reforms, but sought this time to be at their head. Assembling in front of Malacañang on January 7, they described themselves to the press as the “student reform movement,” and the Collegian reported that “Close to a thousand students from the University and other schools rallied before the Malacañang Palace yesterday [Jan 7] … Workers who were on strike at Northern Motors joined the students.” The rally turned, however, from the question of student reform to that of police brutality and the ‘fascism’ of the Marcos administration. This cantus firmus, adopted by group after group in counterpoint, served as the theme of the political fugue that was the FQS.

Rene Ciria-Cruz and Gary Olivar were among those who addressed the crowd. They explained that “the real enemies of the police are not the students, nor the workers and farmers but the American imperialists and the hacendero-comprador class who exploit them indirectly.” In arguing that the police were somehow really the class allies of the students, workers and peasants, Ciria-Cruz and Olivar were repeating the perspective of Joma Sison, head of the KM, in his 1966 speech at Ateneo, “Nationalism and Youth,” when he had referred to the “good elements” of the police force, “sympathetic to the cause of nationalism,” as the spiritual offspring of Gregorio Del Pilar. With a flippancy of political rhetoric, these spokesmen of the SDK argued to a rally which was in part dedicated to denouncing ‘fascism’ and police brutality, that the police were in truth the allies of the assembled workers and students.

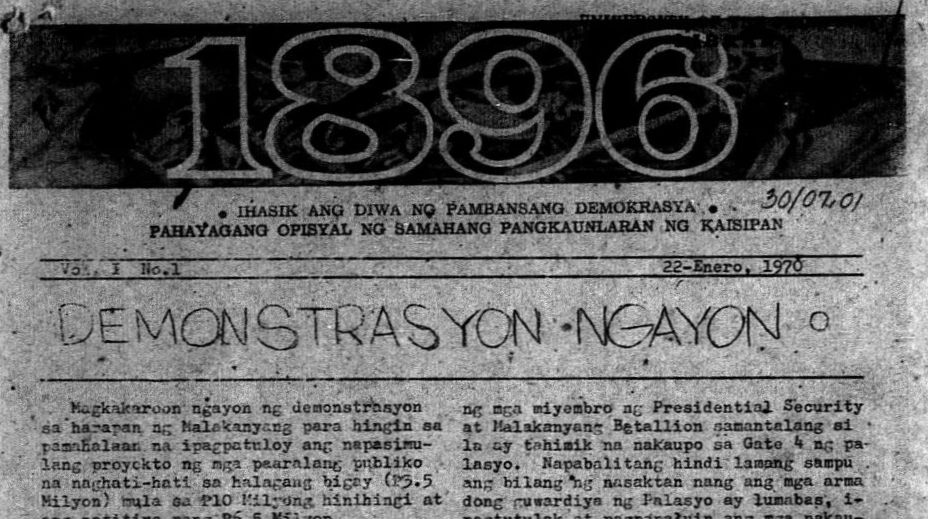

Demonstrations followed on January 16 and 22; the theme of student reform — still audible — was fading, while the staves on fascism augmented. According to the Samahang Pangkaunlaran ng Kaisipan (SPK), students gathered outside Malacañang on both the sixteenth and the twenty-second to request from the government the disbursement of funds which had been promised for public education. The placards and slogans of the assembled demonstrators, however, revealed that the political logic of the emerging movement was tending toward a far sharper conclusion. Over a thousand workers and students from a range of organizations, including KM, SDK, and SPK, rallied on the sixteenth; their signboards read “Justice is a slow process, revolution is faster,” “PC–MPD–military arm of the ruling class,” and “Ibagsak ang pasismo. [Down with fascism]” The assembled demonstrators denounced “the alliance between alien capitalists and the armed forces and the rise of fascism under the Marcos administration.” Rodolfo del Rosario, the Vice President of the National Association of Trade Unions (NATU), and a member of KM, addressed the crowd, denouncing the conspiracy of foreign capitalists [kapitalistang kayuhan (sic)] and the police in suppressing the ongoing strike at Northern Motors — at the time the largest General Motors assembly plant outside the United States — and arresting workers without cause. The union leaders who spoke at the rally “revealed the increasing unrest in the labor sector as they spoke against the exploitative relationship perpetuated by American capitalists in collusion with their Filipino puppets in the business and government sectors.” The demonstrators — workers and students — were violently dispersed by the police.

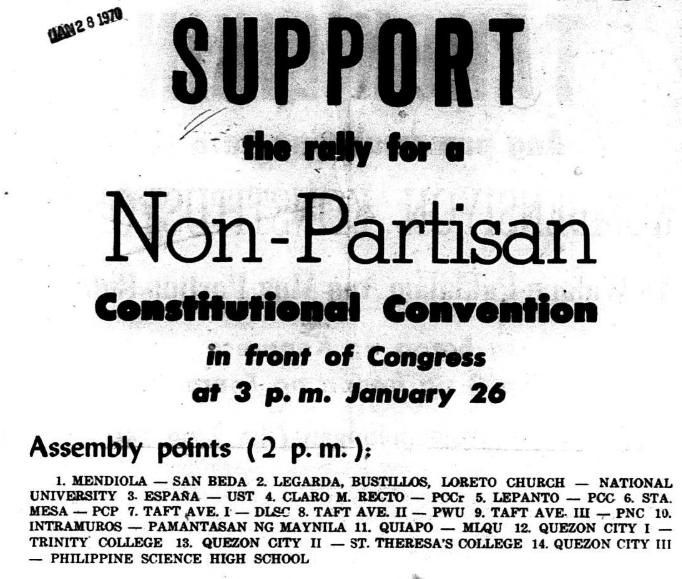

A new theme — neither student reform nor fascism, but a non-partisan Constitutional Convention — was briefly heard during the protests outside of the legislature during Marcos’ State of the Nation Address as moderate student groups initially held the stage — the National Union of Students of the Philippines (NUSP), National Student League (NSL) and the Young Christian Socialists of the Philippines (YCSP), a group tied to Raul Manglapus. Edgar Jopson, head of the NUSP, produced a statement entitled “A Call for a Constitutional Convention Without Interference from Political Parties.” Sison responded with a statement, “The Correct Orientation on the Constitutional Convention,” in which he argued that the “essential nature of the Philippine Constitution since the very start has been its being an instrument of national and class oppression and exploitation.” It was “patently a colonial document on incontrovertible grounds.” The 1971 Convention was thus being formed to raise “false hopes” that it could serve as “a possible means of ‘revolutionary’ change to head off a real armed revolution of the broad masses of oppressed and exploited people.”

Sison hid the fact that the KM had placed working within the Convention at the center of its program in 1967 and that, as late as July 1969, it had remained the core focus of both the KM and SCAUP and had served as the basis of their common campus election platform in the Young Philippines. He now claimed that “the main task of all proletarian revolutionaries and all those who adhere to the people’s democratic revolution is to expose and oppose the 1971 constitutional convention as a farce.” The convention was “another swindle perpetrated on the people.” Both the immediate political orientation of the bourgeois opposition and the mood of the masses had shifted, and the tactic of participation in the Convention was no longer politically viable. The bourgeois allies of the CPP desired an explosion in the streets against Marcos. In a partially articulated but nonetheless palpable fashion, the masses of workers, students and peasants sought a solution to the stranglehold of economic crisis through increasingly drastic political means. The task of the CPP was to subordinate the latter to the former and this required burying, at least for the present, the question of the convention.

A leaflet which the KM produced for the initial January 7 rally concluded with a formulation that encapsulated the fundamental political logic of the CPP and its front organizations in the critical period between the storm and the onset of military dictatorship: “the intensification of the fascistic suppression of the national democratic aspirations of the people by the Marcos military regime only serves to enlist more adherents to the struggle for genuine emancipation from US imperialism and local feudalism.” Fascism, they argued, only causes the movement to grow.

This was the basic logic underpinning all of the mimeographed leaflets circulated by the KM during the First Quarter Storm. Marcos was a fascist puppet, the main representative of US imperialism and local feudalism, and as such he should be the primary target of all protests. The people would rise up to demand national democracy and they would be violently suppressed. This suppression would expose the character of the fascist Marcos regime to even more people, who would then rise up and be suppressed. The people would never be cowed by fascism. The more that Marcos was “fascist” and violent, the more people would rise up. But rise up to what end?

At no point were workers and students educated in the need for an independent struggle of the working class for the seizure of power, or that in order to implement national democratic tasks, socialist measures must be taken. Rather the students were instructed to demand, to request — stridently, but nonetheless to ask — of the ruling class that national democratic measures be carried out. In fact, no political program at all was presented. None beyond the need for what became the clichéd slogan of the movement, “Makibaka, huwag matakot! / Struggle, don’t be afraid!” The act of struggling, of making demands to the state, would precipitate state violence, which would, in turn, cause the movement to grow. This was the entire perspective of the KM during this period.

Whose political interests did the First Quarter Storm wind up serving? Not workers or students. They fought courageously and were bloodied in the affair, but the Stalinist leadership of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and its rival, the Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (PKP), worked to ensure that they did not draw independent political conclusions from the experience, and that workers did not organize themselves separately from the bourgeoisie for their own class interests.

The PKP lost out as a result of the FQS. They fought a rearguard battle to simultaneously negotiate ties with Marcos and maintain support among the youth. This was an impossible task, and they lost a good deal of their political credibility in the process.

The CPP and its front organizations benefited immensely from the FQS. Both the shared barricades of Mendiola and the exposure of the Malayang Pagkakaisa ng Kabataang Pilipino (MPKP), youth wing of the PKP, served to heal many of the wounds which had been caused during the 1967 breach between the KM and the SDK. A generation of students were radicalized by the FQS — some only briefly, but for others it was a life-changing experience — and many found their way into the ranks of the CPP.

The greatest short-term beneficiaries of the storm sat in the board rooms of Meralco and the political headquarters of the Liberal Party. For Lopez and Aquino and their allies, the protesting students were an ideal proxy in their fight against Marcos. These forces aspired to destabilize and overthrow him, and the blood in the streets served this purpose. They did not succeed in this, however.

In the end, the events which began on January 26 1970 set in motion a countdown to martial law. Marcos recognized in the violent demonstrations a pretext for dictatorship. He fomented violence through agents provocateur and began preparing the architecture of a police state.

Thus, by the final week of January, the forces who would decide the fate of the First Quarter Storm were all in place: Marcos, aspiring for a pretext for dictatorship, his bourgeois opponents for violent destabilization; a restive youth and working class; and two Communist Parties, one subordinate to each faction of the ruling class. The storm that burst on 26 January 1970 and the events that transpired over the next three months were among the most explosive in the country’s history.