November 30 marks the fifty-fifth anniversary of the founding of the radical Filipino youth organization, Kabataang Makabayan [Nationalist Youth] (KM), in 1964. While it had only thirty-four charter members, the KM grew rapidly and came to play an instrumental role in the upheavals that shook the country less than a decade later.

Jose Maria Sison, a member of the Executive Committee of the Stalinist Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (PKP), had over the course of the preceeding two years organized support for then President Diosdado Macapagal. Working with Ignacio Lacsina, another leading member of the PKP, Sison arranged for the newly formed Lapiang Manggagawa [Workers’ Party] (LM) to enter into an alliance with the Macapagal administration in mid-1963, merging the LM with the ruling Liberal Party (LP). He orchestrated the founding of the party’s peasant wing, Malayang Samahan ng mga Magsasaka [Free Federation of Peasants] (MASAKA), with funding from Malacañang, and wrote the handbook supporting Macapagal’s land reform program which was published and distributed to the peasantry. In the opening pages of the handbook, Sison praised Macapagal for carrying out the “unfinished revolution” of Bonifacio. The land reform program he was promoting had in fact been crafted by the Ford Foundation.

The party lacked a functioning youth wing and Sison was tasked with creating one, a project which culminated in the founding of KM. By late 1964, however, the PKP’s relations with Macapagal had soured. As the Philippines entered the election year of 1965, the party began looking to establish ties with Macapagal’s rival, Ferdinand Marcos, the presidential candidate of the Nacionalista Party (NP). Sison orchestrated the support which the LM, MASAKA and KM gave to the NP, and in November 1965, one year after its founding, the KM backed Ferdinand Marcos for president, hailing him, in the language of Stalinism, as a representative of the “progressive section” of the “national bourgeoisie.”

What follows are edited portions of my doctoral dissertation, Crisis of Revolutionary Leadership: Martial Law and the Communist Parties of the Philippines, 1957-1974, on the founding of the KM. For notes and references, please consult the original work.

While the PKP by 1963 had a substantial hold over the labor movement through the Lapiang Manggagawa, and a growing presence in the peasantry through MASAKA, the weakest aspect of its organizational expansion was its work among youth. Despite Sison’s political origins in the Student Cultural Association of the University of the Philippines (SCAUP), the influence of the PKP among youth and students from 1962 until mid-1964 was negligible and stagnant. While Sison traveled to Indonesia, formally became a Stalinist, and rose to leadership in the PKP, SCAUP had carried on with its old mixture of anti-clericalism, nationalism, and the cult of Claro M. Recto.

The leadership of SCAUP was turned over to Jose David Lapuz, who proved incapable of developing it into a viable political organization in the wake of the departure of Sison. Lapuz seemed fixated far more on his own reputation than the building of a youth movement. When Lapuz wrote his own biographical by-line in the Collegian, he described himself as “one of the few nurtured on the civilization of Europe,” and he was forever attempting to demonstrate his superior level of culture. On February 26, 1964, Lapuz ran an announcement in the Collegian which read: “L’Association Culturelle de Etudiante de L’Universite de Philippines (SCAUP) will tender a reception today … Those desiring to attend the reception may do so upon payment of P3.00 to Jose David Lapuz.” The only interest advanced by the poorly formatted French was Lapuz’ own ego. The conclusion to an article he wrote on Recto, entitled “Claro M. Recto: the parfait knight of Filipino Nationalism,” is sadly representative of his writing: “The last time I saw [Recto] … it was as though his person fumigated with incense whenever he walked by … He is gone now and I am sure he will have no replacement in this our country, or in this my heart. For he left me, even though defeated, a hope, a promise, a symbol, a fragment from out his heart to serve for one who will come after. And, by God! I promise to preserve, to continue.”

In May 1964, Lapuz involved SCAUP and Joma Sison in the filing of criminal charges with the police. Sison testified on behalf of Lapuz that Leonardo Quisumbing, then UP Student Council chair, had slapped Lapuz in response to one of Lapuz’ articles. The police charges were the culmination of a lengthy series of petty squabbles between the two. Lapuz had passed to the Collegian for publication a resolution which had not been signed by Quisumbing, and Quisumbing compelled Lapuz to formally apologize. Lapuz wrote an article accusing Quisumbing of corrupt leadership, and in response, Lapuz claimed, Quisumbing slapped him. In addition to the filing of criminal charges with the police, Lapuz wrote an open letter to University President Carlos P. Romulo, “Permit me, I implore you, to be concerned with the just glory of our University and to tell you that its good reputation is now threatened with the most abominable, unutterable slur.” Quisumbing was ordered to apologize.

Just how far SCAUP had degenerated by mid-1963 was made clear in a column in the Collegian written by SCAUP member, Rene Navarro, in which he decried “progressives” for pursuing “lost causes,” and characterized the editorial statement of the Progressive Review — a journal edited by Sison and closely tied to the PKP — as using “communist jargon … which will no doubt arouse the indignant sensibilities of decent men.” SCAUP had over the course of three years degenerated from protesting against the red-baiting of the Committee on Anti-Filipino Activities (CAFA) to seeing one of its leading representatives use the pages of the Collegian to denounce the Progressive Review for “communist jargon.”

Despite SCAUP’s organizational struggles, by the beginning of 1964 it was affiliated with the same circle of people as the PKP, and, like the party, was supporting Macapagal. Lapuz, at the head of SCAUP, promoted Macapagal in the same manner as the LM, although in a style that was only his. In a letter to the Collegian in response to a speech delivered by Macapagal on January 9 to the Rotary Club, Lapuz wrote “As one who may be likened to a keen-eyed eagle perched on the highest house-top in matters pertaining to international diplomacy and foreign, external politics, I viewed with great and curious interest this latest development in our foreign policy … President Macapagal in this revolutionary address before the Rotarians broke with the past … The Filipino — what a beautiful man is the Filipino now! in foreign policy, how express and admirable! in action how like an Asian!”

SCAUP, based exclusively at UP and under the leadership of Lapuz, ‘full of high sentence, but a bit obtuse,’ was not a viable youth front for the PKP. A new organization needed to be founded. In June 1964, Sison was given employment teaching social sciences at the Lyceum, an institution owned by the Laurel family who had longstanding ties to the aboveground elements of the PKP. The Lyceum would serve as the base of operations for the creation of the party’s new youth organization, the Kabataang Makabayan (KM).

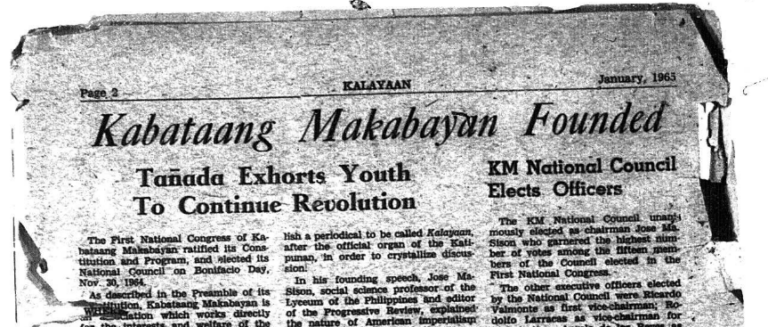

On November 30 1964 — Bonifacio Day — the KM was founded, marking the culmination of two years of struggle by the PKP to create a functioning youth organization. The founding congress was held at the YMCA Youth Forum Hall with thirty-four charter members in attendance, most of whom had participated in a rally staged on October 2 outside Malacañang. The elected leadership of the new organization was largely drawn from SCAUP and were personally close to Sison. The KM later recorded that “student members came mostly from the University of the Philippines (UP) and the Lyceum of the Philippines. … The young worker members came from Lapiang Manggagawa, particularly the trade unions affiliated to the National Association of Trade Unions.” As the KM grew, however, the majority of its formal membership was drawn from “the children of peasants organized under the Malayang Samahan ng Magsasaka (MASAKA).” The fault-lines which would split the party between Moscow and Marcos, on the one hand, and Aquino and Beijing, on the other, ran between these class constituencies. The ranks of peasant youth, brought into the KM as by levy upon MASAKA, shared the conservative political education of their parents; what to them were the radical phrases of the Red Book? Small land-ownership was the solution to the country’s social ills, and the PKP leadership had assured them that the president — first Macapagal and then Marcos — could through patient, legal means be pressured to implement land reform to the advantage of the peasantry. The working class and university based youth, radicalized by social crisis and global political ferment, needed more than the pap which the party proferred to the peasantry and as Sison held up Mao as the radical alternative to the conservative Moscow bureaucracy, the majority of them followed.

Joma Sison was elected chair of the new organization; Sen. Lorenzo Tañada was made an honorary member and consultant of the KM, and delivered the closing address of the founding congress. Tañada, who had taken up the mantle of Claro M. Recto, would be integral to the development of the front organizations of the Communist Party over the next six years. The KM National Committee established the ambitious goal of expanding the youth organization’s membership to five thousand within the next six months. The founding congress produced a forty-one page handbook. Reading and agreeing with the content of this handbook was a required step for joining the KM and the basic educational work of the KM was structured around the documents it contained.

The first document in the handbook was Joma Sison’s speech to the founding congress. Sison opened with a brief history of the Philippines, highlighting Spanish colonialism, American imperialism and the uninterrupted struggles of the “Filipino people” in opposition to conquest and occupation. His speech was devoid of an international perspective. He traced the roots of the KM to Bonifacio and to Rizal, making no mention of the struggles of workers in other countries or of Marxism. He deployed Marxist phrases in an incoherent fashion, but disguised their origins. He attributed, for example, the discovery of the historical roots of imperialism not to Lenin but to Rizal, who “noticed that it was a necessity of a capitalist system, reaching its final stage of development — monopoly-capital, to seek colonies.” Sison was clearly attempting to use Rizal as a cover for Lenin’s ideas, but it is noteworthy that he gets Lenin wrong. Colonialism predated imperialism by centuries. The imperative of monopoly capitalism was not fundamentally to “seek colonies,” but for the imperialist powers to divide and re-divide the world into rival spheres of influence and control.

Sison continued, “There is only one nationalism that we know. It is that which refers to the national-democratic revolution, the Philippine revolution, whose main tasks now are the liquidation of imperialism and feudalism in order to achieve full national freedom and democratic reforms.” Sison expanded on this: “The youth today face two basic problems: imperialism and feudalism. These two are the principal causes of poverty, unemployment, inadequate education, ill-health, crime and immorality which afflict the entire nation and the youth.” According to Sison, capitalism was not responsible for these social ills, and he claimed rather that an independent national capitalism was their solution. He wrote,

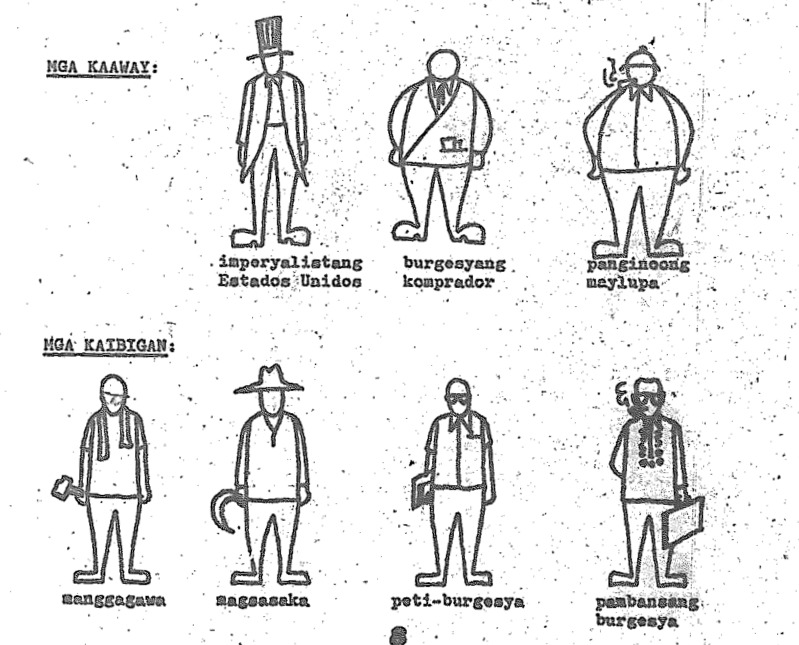

It is the task of the Filipino youth to study carefully the large confrontation between the forces of imperialism and feudalism on the one side and the forces of national democracy on the other side …

On the side of imperialism are the compradores and the big landlords. On the side of national democracy are the national bourgeoisie, composed of Filipino entrepreneurs and traders; the petty bourgeoisie, composed of small-property owners, students, intellectuals and professionals; and the broad masses of our people, composed of the working class and the peasantry to which the vast majority of the Filipino youth of today belong.

He called on KM to “assist in the achievement of an invincible unity of all national classes … against the single main enemy, American imperialism.” What Sison presented in his speech was the undiluted program of Stalinism — not a socialist but a national democratic revolution, which would be carried out by a bloc of four classes, an alliance of capitalists and workers.

The program of the KM took Sison’s formulation of achieving an invincible unity of all national classes and presented this as the KM’s “chief task.” It then concretely presented how the KM would struggle to fulfill this task in four “fields”: economic, political, cultural and security. In the economic field, the KM called for state planning to protect “Filipino industrialists and traders;” “asked” the state for “genuine land reform;” and called on the state to open diplomatic ties with the socialist bloc with whom it could negotiate trade and loans in support of Filipino capitalists. The single concrete task specified in the political field was to seek the annulment of the Anti-Subversion Law. In the cultural field, KM called for removing the cultural instruments of American imperialism — the Peace Corps, USIS, AID, VOA, etc., and also demanded wider use of “Pilipino in our educational and governmental system.” Finally, as a means of counteracting “decadence, delinquency and immorality” KM proposed to direct civic work projects, “such as relief work and community improvement projects, and other self-improvement projects.” In the field of security, the KM called on youth to undergo “ROTC and other forms of military training with the clear intention of developing our own security forces independent of American indoctrination.” This was a bizarre conception; the ROTC had been designed from the ground up by the US military. The primary role of the “security forces” in the Philippines had always been the suppression of dissent, and ROTC training was crafted towards this end. The program concluded by calling for the abrogation of the basing treaties.

The next document in the handbook was the constitution, which opened membership to any “Filipino citizen between the ages of fifteen and thirty-five.” Every member was required to pay a one peso application fee, and membership dues of two pesos a year. The handbook concluded with the closing speech of Lorenzo Tañada, in which he called on the youth to make their voices heard. “Here is perhaps the most significant task that the youth can undertake towards building the nation. You are not yet decision-makers. The direction of national affairs is not yet in your hands. But you can speak forth as often and as publicly as you can on national issues of the day. When your elders prove stubborn or recalcitrant, dramatize your stand, demonstrate, march and rally in support of a cause.”

In sum, the founding documents of the Kabataang Makabayan made clear the political character of the organization. There was no mention within its program of a single measure in the interests of the working class, as somehow support for national capitalists would cause benefits to trickle down to workers. The KM was founded as a reformist youth organization to carry out pressure politics in the interests of the national bourgeoisie. Immense social struggles would, in less than six years, thrust this small group to the center of the country’s political life, transforming it from a bit player into a decisive factor in the life-and-death struggle over dictatorship.

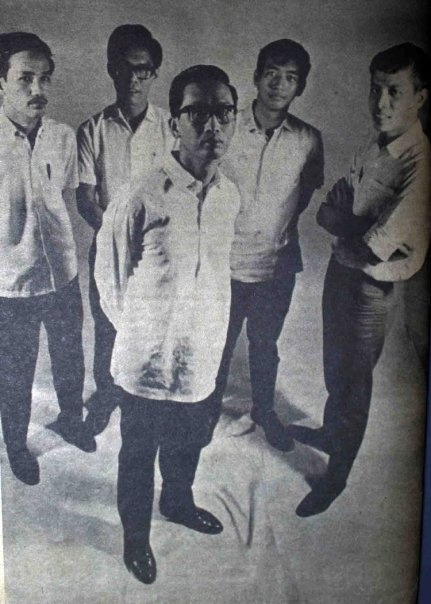

L-R, Ibarra Tubianosa, Carlos del Rosario, Joma Sison, Leoncio Co, Art Pangilinan. (Graphic, 13 Mar 1968).

Less than a year after its founding, the KM, under Sison’s leadership, endorsed and supported the candidacy of Ferdinand Marcos for president on the grounds that he would keep the Philippines out of America’s war in Vietnam. Within two weeks of his election, Marcos told the Washington Post in an interview with Stanley Karnow that he would be deploying a contingent of Filipino troops in support of Washington’s war efforts.