Fifty years ago, on Saturday, May 1 1971, police and military forces in the Philippines, who had been deployed on the roof of the Congress building as snipers armed with machine guns, opened fire on four thousand protesting workers and students. They mercilessly strafed the crowd, firing on anyone who moved, including Red Cross workers and emergency personnel who attempted to approach the bodies of the wounded. A military helicopter circled overhead and dropped tear gas on the panic stricken crowd. Plainclothes officers beat the fleeing demonstrators with truncheons. When the bullets ceased flying, three unarmed protestors lay dead and eighteen were wounded, many severely. The event became known as the May Day massacre. Citations and further details for what follows can be found in my doctoral dissertation and in my forthcoming book, The Drama of Dictatorship: Martial law and the Communist Parties of the Philippines.

The events of May 1 1971, like the Plaza Miranda massacre in January earlier that year, were buried beneath the headlong rush of events that characterized the period between the First Quarter Storm at the beginning of 1970 and the imposition of martial law in September 1972. I attempted to outline the thrust of these developments in a recent lecture sponsored by the UC Berkeley Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Three Grenades in August: Fifty Years since the Bombing of Plaza Miranda in the Philippines. A sense of the growing social unrest among the working class and the advanced preparations for authoritarian rule in the ruling elite is palpable throughout this period. This was not a national phenomenon; it was rather a specific expression of what was a global period of social upheaval and repression.

In December 1970, Philippine Military Academy (PMA) instructor Victor Corpus staged a raid on the PMA armory and defected to the New People’s Army (NPA) of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP). In January 1971, the police opened fire on striking workers gathered at Plaza Miranda, killing four and injuring over one hundred. The next month saw the erection of barricades in downtown Manila and on the campuses of the University of the Philippines Diliman and Los Baños. Seven students and youths were killed in confrontations with the police and military. In March, the CPP attempted to seize control of a number of labor unions by subterfuge and succeeded in splitting them. The CPP Central Committee member responsible for its engagment with the labor unions, Carlos del Rosario, disappeared and was never found again. In April, Army Lieutenant Crispin Tagamolila defected to the NPA. Workers were going on strike throughout the country, including at Clark Airbase, the nerve center of US empire in Southeast Asia during the war in Vietnam. In August, the Liberal Party election rally at Plaza Miranda was bombed. Marcos suspended the writ of habeas corpus and used the opportunity afforded him to round up hundreds of ‘radicals.’ It was a dry run for martial law a year later.

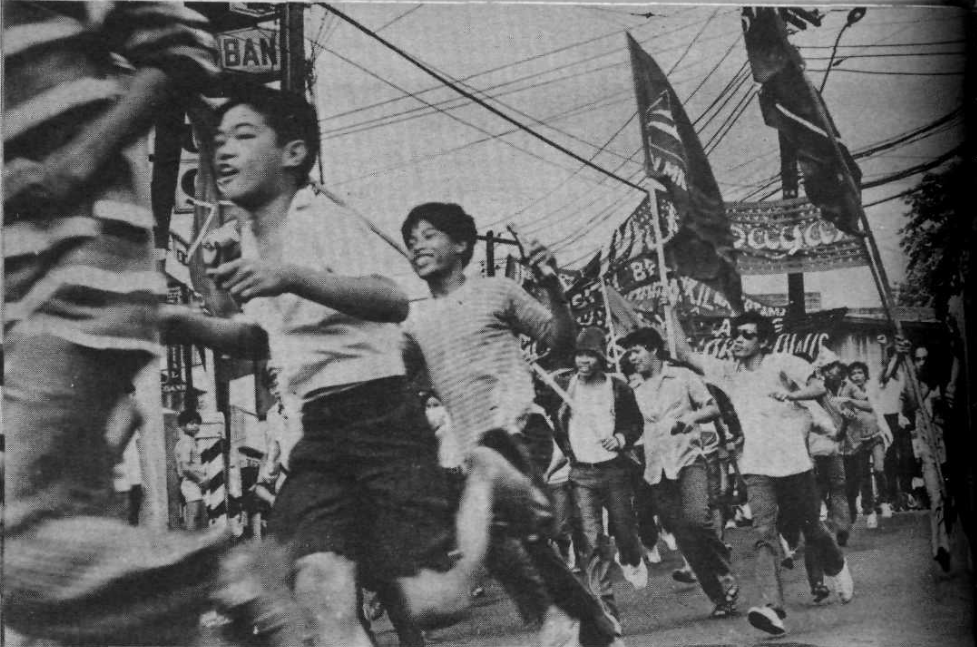

It was in this heated context that workers and youths marched on May 1 from the España rotunda down the length of España, across the Quezon Bridge and gathered on P. Burgos in front of what was then the house of Congress and is now the National Museum of Fine Arts. Military helicopters ominously followed them as they marched toward Congress. The newpapers of the day listed the names of many of the marchers, among them Boni Ilagan, Judy Taguiwalo, Virgilio Almario, Sixto Carlos Jr., and Maria Lorena Barros.

They gathered in front of Congress, waving their flags and banners. Food and drink vendors passed through the crowd peddling their wares to the thirsty demonstrators. Behind them stretched the grassy expanse of the Muni Golf Links skirting the rough southern bulwarks of Intramuros. To the north was Plaza Lawton, to the south, Luneta.

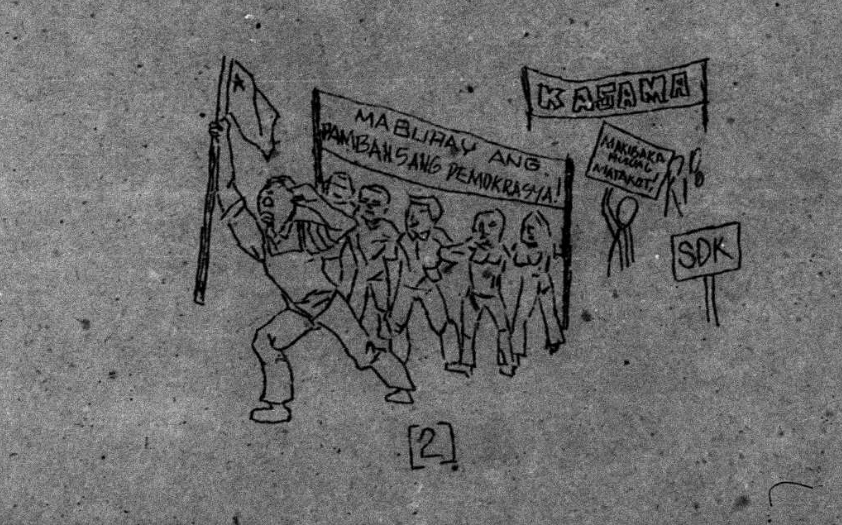

The assembled forces were led by the various national democratic organizations that followed the political line of the Stalinist CPP – the Kabataang Makabayan (KM, Nationalist Youth), the Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan (SDK, Democratic Federation of Youth), and the newly founded labor union umbrella group, KASAMA.

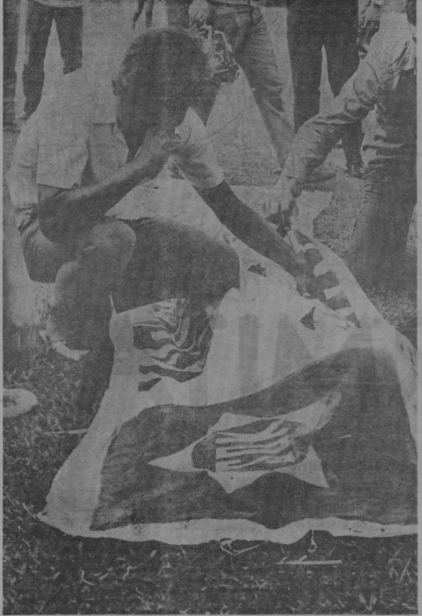

At five in the afternoon, Jimmy Lacsamana, president of a union currently on strike, addressed the crowd. A contingent of the KM from Tondo arrived at this point, and someone attempted to lower the Philippine flag and reverse it, so that the red field was uppermost. A member of the armed forces in civilian clothing struck the person touching the flag, and threatened to kill him if he took the flag down. US Tobacco Corporation Labor Union Vice President Peter Mutuc, who was emcee of the event, took the microphone and attempted to calm the crowd. According to journalist and screenwriter Ricky Lee, who was present at the event, some of the demonstrators began throwing pillboxes, small handheld explosive devices, at the troops in front of the congressional building.

It was at this point that the protest became a massacre. Members of the 55th company of the Philippine Constabulary, pulled away from an ‘anti-Huk’ campaign of counterinsurgency warfare in the countryside, had been incorporated into the Metrocom the day before. The Metrocom, the Metropolitan Command, was an anti-riot squad recently created with funding from the CIA, that gave the Philippine Constabulary (PC) jurisdiction in Metro Manila for crowd control and suppression. The members of the 55th were deployed as snipers with machine guns on the roof of the legislature and trained their sights on the crowd. There were snipers on roofs in Intramuros as well, prepared for those who would flee. Uniformed police and plainsclothesmen surrounded the demonstrators, armed with guns and truncheons.

The rooftop snipers began to spray the crowd with machine gunfire. Panic gripped four thousand demonstrators and they scattered in all directions. They screamed, frantically and ineffectually attempted to hide behind lampposts or within a scrawny thicket of gumamela (hibiscus). They fell over each other in their panic. Ricky Lee recounts toppling over a kariton, a cart, laden with steaming corn. The military helicopter circling overhead began to drop teargas cannisters on the desperate scattering protestors. Tsinelas – rubber slippers – and books were cast about on the pavement. The machine gunfire continued unabated.

Ninotchka Rosca wrote, “A deadly rain drops from the impassive facade of Congress, from above the granite heads of the late nationalist leaders Sergio Osmeña and Manuel L. Quezon.”

Lee captured the horror of this moment, “magsasaniban ang mga daing at pasaklolo at iyak sa haging ng bala at sa ratatat ng armalite” / “the wails and pleas and crying mingle with the whizz of bullets and the ratatat of armalites.” A vendor of palamig, roadside iced desserts, reported that the bullets skipped off the pavement and the grass like a swarm of “tipaklong” or grasshoppers.

Richard Escarta, known to his friends as Dick, was a Secretarial Student at Rodriguez Vocational School in Sta. Mesa Heights. His father was a security guard in a bank in San Juan. Dick had recently married, and he and his wife, Amerita, had a four month old child. The day before the May Day rally, she had asked Dick if they could get a photograph taken of their child so they would have something to send home to the province. He told her sadly that they could not afford it.

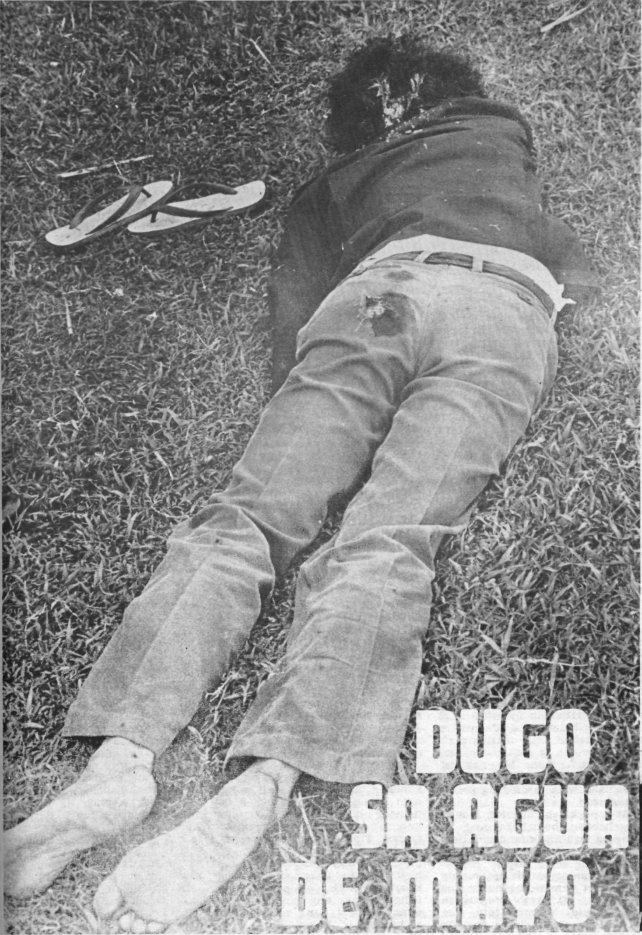

Dick ran from the machine gunfire and hid, only to find that he had lost his tsinelas and he could not afford to lose them. Bent over, he raced back to P. Burgos and managed to recover his footwear. When he made it back to the golf course, however, he was shot in the thigh. “Tinamaan na ako” / “I’m hit,” he called out. A second bullet hit Dick Escarta, this time in the head, shattering his skull. He fell forward, his face buried in the grass, and was still.

Liza Balando had moved to Manila from Samar three years earlier when she was 19 years old. She had initially found work as a domestic helper but eventually landed a job in Caloocan at Rossini’s Knitwear, where she worked as a cap seamer making three pesos a day. She was a proud member of the union in her workplace and by everyone’s account was of a vibrantly cheerful disposition. She made it as far as the grass before she was shot dead. It would be more than a week before her family in Samar learned what had happened to her.

Ferdinand Oaing was only sixteen years old. He was a sidewalk vendor and had been radicalized while selling snacks and cigarettes at the fringes of rallies. He became an active member of the Quiapo branch of the KM. Ferdie ran beside his fifteen year old friend, Dante Cocquia, and they managed to make it to a dip in the grass where they took shelter. Seeing the bodies of the wounded writhing on the pavement, Ferdie ran back to attempt to pull one to safety. A bullet caught him in the forehead. Dante ran to his side and with his last breath Ferdie asked his friend to take the few items in his pockets so that the Metrocom would not get their hands on his only possessions. Dante dragged Ferdie’s body across the pavement toward safety, but as they got out of the range of gunfire and approached an ambulance, a Metrocom officer stepped up and cursed Dante and chased him away. Ferdie’s corpse was left on the pavement.

Still the machine guns fired. A quarter of an hour had passed and bullets continued to chip away at the pavement. Red Cross workers and emergency rescue personnel had arrived in ambulances and attempted to crawl to the bodies of the wounded, but the snipers’ guns spit fire and they retreated.

Plainsclothes officers waited in Luneta and swung their truncheons, beating those who ran south for safety. Guns fired from rooftops in Intramuros. Rosca reported, “Roberto Valenzuela is shot in the face – gun emplacements seem to be elsewhere, in the surrounding buildings, other than Congress itself – and falls writhing to the ground.”

Twenty minutes after the massacre had started, the guns fell silent. Three demonstrators were dead, eighteen of the wounded were hospitalized. The number of wounded is always far higher than that reported in the papers, as only those hospitalized are mentioned. The injured and the bleeding workers could ill-afford a trip to the hospital and many bandaged themselves. Only the severely injured went to the hospital.

The police arrested over a score of demonstrators and many of those arrested reported that they were beaten in the precinct and in their cells.

The umbrella organization, Movement for a Democratic Philippines (MDP), staged a press conference on May 2 and denounced the massacre. Spokesperson Chito Sta. Romana, standing beside Ericson Baculinao, announced that they would stage an indignation rally on May 8. In Australia, a group of demonstrators gathered in front of the Philippine Embassy and threw stones.

Dick Escarta’s father, the security guard, told the press that he had no idea how he would pay for his son’s funeral (“di maubos-isipin kung saan kukuha ng perang maipagpapalibing sa anak.”) And then this man who admitted that he had never been a political person told the press “sasama ako sa SDK, ipagpatuloy ko ang naiwang gawain ng anak ko, kahit ako pa ang mamuno.” (I’m going to join the SDK, I will continue the work left behind by my son, even if I need to lead.)

The May Day massacre of 1971 was part of a ongoing struggle between emerging mass opposition to war, to inequality and exploitation, and to the threat of dictatorship, on the one hand, and the increasingly brutal apparatus of state repression defending capitalist property relations, on the other.

The great tragedy of the period of 1970-72 was that all of this courageous opposition was subordinated to the interests of rival sections of the ruling elite by two rival Stalinist parties. The old Moscow oriented Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (PKP) supported Marcos. On May Day, as Marcos’ security forces opened fire on workers, the Movement for the Advancement of Nationalism (MAN), a broad front organization fully in the camp of the PKP, published a statement, Dissent and the Proletariat, that read, “For a nation reeling under imperialism, no effort should be spared in winning over the nationalist bourgeoisie, fostering a United Front, and pushing through the national democratic revolution.” On the basis of this anti-Marxist, nationalist rationale – an alliance with a section of the capitalist class – MAN would organize support for Marcos’ candidates in the 1971 mid-term election.

The KM, SDK, and MDP meanwhile rallied the social outrage at the massacre in front of Congress and brought it before the rostrum of their bourgeois allies in the Liberal Party (LP). The elite politicoes of the LP were becoming increasingly adept at mouthing the slogans of the front organizations of the CPP.

Two examples from rallies staged in the summer of 1971 will give a sense for the interaction of the front organizations of the CPP and the Liberal Party. On May 22, the KM, SDK, and MDP staged a rally at Plaza Miranda to denounce Marcos. Senatorial candidate, and scion one of the most powerful political dynasties in the country, John Osmeña addressed the crowd, alongside Baculinao and Sta. Romana. Osmeña waved a book before the audience, a copy of the penal code. He cursed the “fascism” of Marcos and then set the book on fire, burning it on-stage while the crowd cheered. In Cebu City, Osmeña’s home turf, the political ties of the KM and the LP took on even more grotesque form. On June 12, the KM and SDK staged a rally for Osmeña, marching to the city center. Voltaire Garcia spoke and SDK leader Jun Alcover introduced Osmeña. Osmeña came on stage as the Cebu City Band played the Internationale, and the Philippine Constabulary and local Boy Scout troop stood at attention. Resil Mojares wrote a letter to Asia Philippines Leader describing the event, “Rep. Osmeña struck a responsive chord in the crowds as he repeatedly rapped the fascist administration of President Marcos, the imperialist control of the economy, the excesses of the feudal landlords and big compradors, leading one to wonder, as he went on with his speech, whether we have here the beginnings of a Liberal Party design to ride back into power by representing itself as progressive through a co-optation of the vocabulary of the radicals.” This is precisely what was occurring, and it was a co-optation gladly facilitated by the front organizations of the CPP. Mojares wrote that “The Cebu celebration was, from the activists’ standpoint, an exercise in the ‘united front’ for National Democracy. It was, from the standpoint of City Hall, ‘a chance given for the activists to prove themselves,’ and perhaps, too, an occasion for the officials of ‘Osmeña city’ to win students support for City Hall’s own election-oriented plans.”

In service to its alliance with the elite opposition, the CPP and its front organizations channeled all social outrage in an exclusively anti-Marcos direction. They did not criticize capitalism or state repression, but only the President himself. Even hatred of the police, who had opened fire on the ranks of the demonstrating workers of May Day, was redirected by the forces of the CPP. By October, as the LP campaign was in full gear, protest marches had been turned by the KM into election rallies. As a mass demonstration marched through Caloocan, the city where Liza Balando had worked in poverty and wage slavery, the KM directed the marchers to chant, “Mabuhay ang makabayang pulis!” / “Long live the nationalist police!”