One of the more important tasks for an historian is bringing the experiences and lessons of history to bear upon contemporary developments. As students in the Philippines are currently organizing strikes demanding, in increasingly political language, an end to government neglect in the face of multiple natural and social catastrophes, it seems an appropriate time to review the massive student strikes of 1969.

The following is drawn from my 2018 doctoral dissertation, Crisis of Revolutionary Leadership, and citations and sources for quotations can be found in it.

Nineteen sixty-nine opened with an explosion of student strikes in Manila, a bellwether of the brief, heady epoch of storm and dictatorship that followed. The strikes originated among working class youth in the university belt district, outraged by exorbitant tuition rates and decrepit facilities; by February, the majority of Manila’s universities had been shut down. Some members of the newly founded Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and the Kabataang Makabayan [Nationalist Youth] (KM) participated in the strike wave, but they did not inspire it nor did they lead. Jose Ma. Sison, the KM, and the Samahan ng Demokratikong Kabataan [Federation of Democratic Youth] (SDK) sought to stymie the protests and used the slogan of “Student Power” to redirect emerging social anger behind the banners of nationalism.

The preponderance of higher education in the Philippines was concentrated in Manila and disseminated from privately owned, profit-driven institutions. Their facilities stood clustered along Recto on the northern bank of the Pasig, and within the squat stone walls of Intramuros on its south. Most were crowded, multi-story affairs to which entrance was afforded by a single roadside gate under the watchful eye of armed security guards, who inspected the entering students’ uniforms and identification cards. There were in 1969 over half a million college students in the Philippines, one of the highest college enrollment per capita figures in the world. The majority of these students came from working class and peasant families, and were working their way through school — they were janitors on the night shift, stringers for newspapers, secretarial assistants for the university administration, and sales clerks on Escolta.

From Recto, traverse the length of Quezon Boulevard past the circumferential Highway 54 — now renamed de los Santos, but the name had yet to take — and you would arrive in Diliman on the outskirts of Quezon City. There the state university — UP — sat in seeming rural isolation, its expansive facilities still spreading outward into fields of cogon and talahib. At its southern and eastern fringes were the impoverished communities of Cruz na Ligas and Balara, pushing towards Marikina. Twenty-five centavos and a thirty minute jeepney ride could get you from Diliman to Recto, but a lifetime of labor would not have gotten most students in the university belt into the state university. UP provided an education to the children of the elite and the upper middle class, but also to the most outstanding scholars throughout the nation. The valedictorian of an impoverished provincial high school could be expected to attend the state university, and on a full scholarship. For the rest of the students, they would work their way through school downtown. Finally, there were the elite religious schools — Ateneo, La Salle, San Beda. These were the enclaves of the extremely wealthy, their corridors of power reserved to cassocks and caciques. They were entirely quiescent in 1969. It was the class divide between Recto and Diliman that shaped the course of the protests.

Student Strikes

The global climate of student unrest in the summer of 1968 provided the initial impetus to the protests that began in the Lyceum and set fire to the fuel of student grievances throughout downtown Manila. Nick Joaquin, writing in the Philippines Free Press in September 1968, anticipated that the events in Paris would be emulated by the “anarchs of academe” in the Philippines, but he had his eye on the “groves of Diliman” not the pavement of Recto. The government, too, anticipated a surge of student protests. Aquino, in an attempt to channel and win the support of the emerging unrest, drafted a Magna Carta of Student Rights, which codified a set of limited rights and obligations for students, asserting, for example, the students’ right to free assembly on campus. He did not, however, address the skyrocketing tuition rates and crumbling infrastructure that set off the 1969 explosion.

Writing in November 1968, in direct response to Nick Joaquin’s article of two months prior, Jose Ma. Sison, about to found the CPP, attempted to subordinate the anticipated protests to the national democratic movement. He held up the Red Guard in China as the model for such struggles, and derided the “ultra-revisionist youth” of Eastern Europe. To succeed, he wrote, “the growing ferment manifested often by student action” needed to adopt the program of national democratic revolution articulated by the KM, by demanding “the national-democratic reorientation of our educational system.” What this amounted to, as we will see, was the demand that universities appoint members and allies of the KM and SDK to faculty positions.

Sison’s perspective was in keeping with the immediate class interests of the leadership of the Communist Party which was founded in the month prior to the eruption of the protests. The heads of several of the institutions in the university belt were key political allies of the newly formed CPP. Nemesio Prudente, the president of the Philippine College of Commerce (PCC) [later renamed Polytechnic University of the Philippines (PUP)], had studied at the University of Southern California (USC) where he had been heavily influenced by Herbert Marcuse in the early 1960s and espoused the ideas of the New Left. His campus was a political haven for the KM. Carlos del Rosario, the head of the PCC Political Science department, was Sison’s brother-in-law, and, in 1969, a member of the Party’s central committee. The Lyceum, owned by the Laurel family, was likewise a base of operations for Sison’s group. Sotero Laurel happily hired the leadership of KM to serve as faculty members at Lyceum, including Joma Sison, Jose David Lapuz — who chaired the Political Science department, Art Garcia, and Jose Luneta.

Lyceum student Rene Alejandro wrote a regular column in the campus student paper — The Lyceum — during the 1967-68 school year in which he detailed a number of grievances that students were routinely expressing regarding the school, largely having to do with school fees and the general disrepair of the facilities. The Laurel administration responded in the first semester of 1968, suspending Alejandro from the school for one year, and suspending the publication of The Lyceum for the majority of the first semester. The journalism students at Lyceum responded by publishing their own paper, The Reporter. Students circulated a petition in defense of Alejandro, calling for his reinstatement, but the school administration refused. In December, at the opening of the second semester, an additional three members of The Lyceum staff were expelled and all four students physically barred by security from entering the campus. The cause of the suspended students and their advocacy of improved school facilities and reduced tuition fees found broad sympathy among students throughout the University Belt in downtown Manila.

Jose Lacaba wrote that

On January 13 [1969], the Guilder, official publication of the College Editors Guild, reported: “The case of the three dismissed Lyceum scribes appears to have stirred a tempest of student unrest as sympathizing students plan to stage a protest demonstration soon if no justice is done them by the proper authorities.”

On January 22, striking students formed a picket line at Lyceum but initially only drew about thirty students to their ranks. The picketers formed the Lyceum Student Reform Movement and circulated a leaflet that concluded: “Let us raise the banner of student power!” The Laurel administration responded to the picket by suspending classes at Lyceum for one week, hoping that the protests would disappear in the interim. Far from disappearing, they spread.

The next day students at Far Eastern University (FEU) formed the FEU Student Reform Movement and likewise went on strike, demanding a “reduction and itemization of tuition fees.” They also “objected to the security guards’ uniform, which is combat fatigue, and their arms, which include carbines, Armalites, and riot guns.” On January 24, three thousand demonstrating students at FEU “broke decorative pots along the streets that border the university, hurled stones at the school buildings and burned placards.” Morayta was closed to traffic. On the same day a group calling itself the Movement of Students for Reforms (MOSTURE) at FEATI distributed a manifesto demanding improved conditions and academic freedom.

On January 27 the police arrested two of the Lyceum student leaders “for their belligerent attitude.” Denouncing the arrests, the striking students attacked the squad car, causing serious damage to the vehicle. Sotero Laurel, head of the Lyceum, refused to meet with the protesters and issued a statement that he was determined to expel the three students. He stated that “a school has the right to defend itself against or rid itself of those who would seek to harm it.” The next day the protest at Lyceum again turned violent as striking students were being prevented by security guards from exiting university buildings. A crowd of students gathered, angrily demanding that the guards allow the students to leave. One of the guards fired a warning shot with his shotgun. Students began throwing rocks. The guards beat some of the students, and at least one student was shot. A fire truck arrived and attempted to disperse the students with water; the students stoned the fire truck. Laurel finally agreed that he would meet with the students on the next day, provided they dispersed. Lacaba wrote at the time that “what happened at the Lyceum that night was by far the most vehement expression of dissent in recent history of the Filipino youth.”

On January 29, students at the University of the East (UE) walked out of classes to protest “exorbitant and unreasonable fees,” and four thousand students from Manila Central University started a boycott of classes protesting “the deplorable conditions of the university” and demanding a reduction in fees. On January 30, ten thousand students at FEATI violently demonstrated, hurling rocks and classroom furniture. On the same day University of Manila students went on strike and classes did not resume until February 20. On January 31, the Student Movement for a Better Mapua at the Mapua Institute of Technology (MIT) led a demonstration of two thousand students demanding a reduction of fees and the improvement of facilities “which turned violent;” no other details are available. Also in the last week of January, students at the Philippine College of Criminology went on strike. On February 3, a group calling itself the Thomasians for Reforms Movement (TRM) launched protests at the University of Santo Tomas (UST), and stones were thrown. On the Fourth, the students at Manuel L. Quezon University (MLQU) went on strike.

By the first week of February all of the universities in the university belt had been shut down by student strikes, many of which had responded forcefully against violent suppression. These included the Philippine Maritime Institute, February 1; St. Catherine’s School of Nursing, February 3; Araneta University, February 6; Arellano University, February 7. The strikes began to spread beyond Manila. Students at universities in Bacolod, Cabanatuan, Laguna, Laoag, and Cebu all began to go on strike as well.

And at Diliman …

At the end of January the UP Student Council worked to get involved in the explosion of student protests. As one strike followed another downtown, Diliman was being left in the wake of political developments and the majority of the council blamed Student Council Chair Antonio Pastelero for poor leadership. Council representative of the Partisans, the UP campus party of the SDK, Jerry Barican threatened Pastelero with impeachment, but Pastelero vowed to resign if requested. The council passed a resolution, by a vote of twenty-four out of twenty-nine councilors, calling on Pastelero to resign. He refused.

On February 4, UP students launched a strike. They presented twelve demands to the administration, of a very different nature from those articulated in Recto. They included the resignations of Iluminada Panlilio and Damiana Eugenio (Eugenio had refused to extend tenure to Vivencio Jose, a leader of the SDK, on the grounds that his “interest in nationalism … made him sacrifice the goals of the courses he was asked to teach”); the security of tenure for faculty members; and the termination of UP’s contracts with the Asia Foundation. The KM, Student Cultural Association of the University of the Philippines (SCAUP) “and other activist groups” initiated the Diliman strike by “stopping vehicles from passing through the University Avenue and asking students to alight from them.” Five activists were arrested. UP Los Baños students likewise went on strike. The students demanded the “the resignation of Dean Dioscoro Umali from all but one of the four positions he is reportedly occupying, security of the tenure of faculty members and workers, and investigation of the American supported SEAMEC and Cornell University grants.” The demand for security of tenure at both Diliman and Los Baños responded to the University’s refusal to renew the contracts of Hilario Lim and Vivencio Jose. On the Diliman campus, newly installed President Salvador Lopez met with the striking students to review their list of demands. The SDK wrote that “On the demands, the students were assured of the administration’s substantial compliance,” including the termination of contracts with the Asia Foundation.

It was not sufficient, the SDK stressed in its February publication, to protest locally. Many of the demands on some of the striking campuses “are too petty, local and limited to cause lasting changes in the servile institutions where the educational system is rooted … Concerted political action in an intra-university basis can change this system … we therefore enjoin the students of Diliman to strike in solidarity with Los Baños and other units.” This expanded vision did not embrace outreach to the ten of thousands of striking students downtown, but even at its broadest reaches it remained within the various units — Diliman, Los Baños, Baguio — of the University of the Philippines. The SDK’s political vision remained intensely parochial and self-interested.

This tactic paid off for the leaders of the SDK. At the end of the 1968-69 school year, the UP Student Council reported that “One of the few February strike demands that have been substantially fulfilled has been the English department change of regime … Nationally known writers like Vivencio Jose, Gelacio Guillermo, Luis Teodoro, Petronilo Bn. Daroy, and Mila Aguilar have been added once more to the department roster.” These incoming and reinstated faculty members were the leadership of the SDK.

Sison intervenes

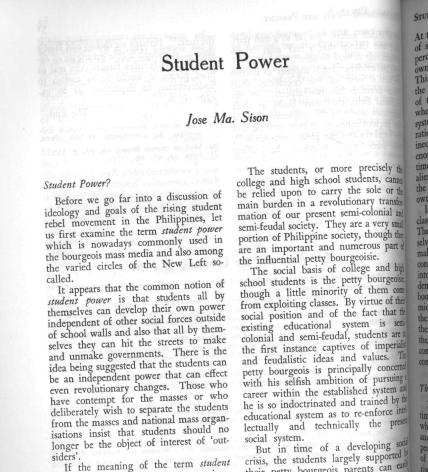

In late January or early February 1969, between the founding of the CPP and the founding of the New People’s Army (NPA), Joma Sison wrote an article for the Hong Kong based Eastern Horizon, entitled “Student Power.” Sison was at pains to establish three points in the article. First, according to Sison, the student strikes in the Philippines were entirely petty bourgeois in origin; second, they were now developing under the leadership, and inspired by the program, of the Kabataang Makabayan; and third, it was imperative for students to take up the “ideology of the working class,” which Sison claimed was national democracy.

Sison began, “the social basis of college and high school students is the petty bourgeoisie, although a little minority of them come from exploiting classes.” As petty bourgeois, the student is thus “principally concerned with his selfish ambition of pursuing a career within the established system.” However, “in time of developing social crisis, the students largely supported by their petty bourgeois parents can easily become agitated when the meager and fixed incomes of their parents can hardly suffice to keep them enrolled in school with the proper board and lodging or with enough allowances.” Sison may have been aptly characterizing the student milieu with which he was himself familiar at UP, largely selfish but easily agitated over their declining allowances. His description, however, was grossly incongruous with the character of the majority of the student population. In Sison’s depiction none of the students — not even the high school students — were from working class or peasant backgrounds, and none were working their way through school.

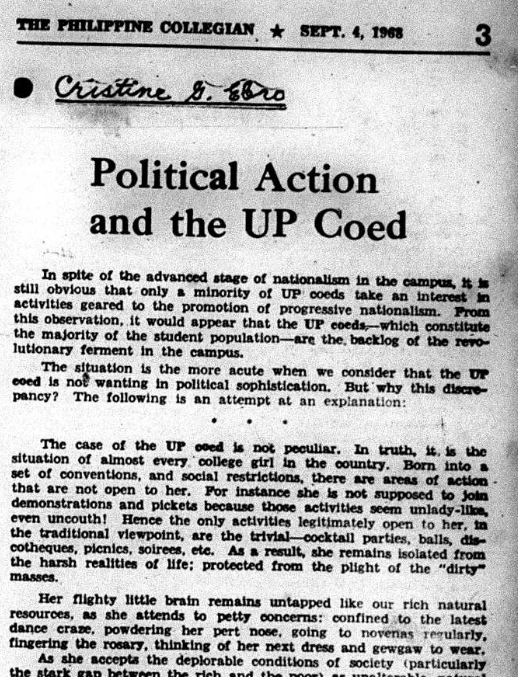

Sison was not alone in this thinking; it characterized the attitude of the KM and SDK leadership generally. Christine Ebro, a Partisan representative and a leader of the SDK, wrote in September 1968 to describe the “situation of almost every college girl in the country.”

Born into a set of conventions, and social restrictions … the only activities legitimately open to her, in the traditional viewpoint, are the trivial — cocktail parties, balls, discotheques, picnics, soirées, etc. As a result, she remains isolated from the harsh realities of life; protected from the plight of the “dirty” masses.

Her flighty little brain remains untapped like our rich natural resources, as she attends to petty concerns: confined to the latest dance craze, powdering her pert nose, going to novenas regularly, fingering the rosary, thinking of her next dress and gewgaw to wear.

Sison, and his entire cohort, had a manifest contempt for the students striking in downtown Manila.

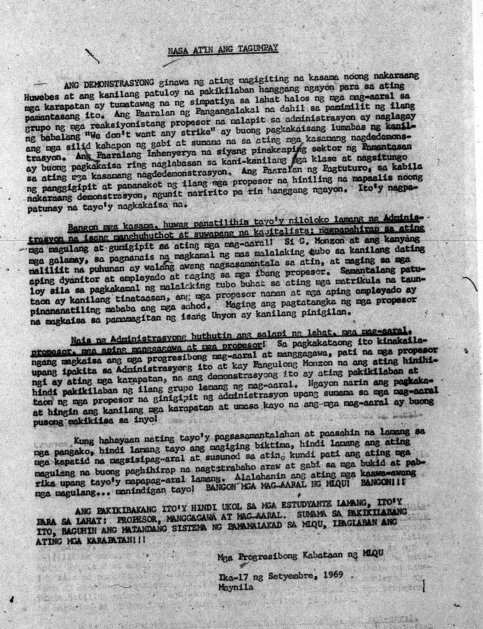

Sison’s conception of the students’ class background and political goals stands in stark contrast to the actual literature being produced by the striking students themselves. On September 17 1969, a group calling itself the “Progressive Youth of MLQU / Progresibong Kabataan ng MLQU,” issued an appeal to the Manuel L. Quezon University student body to support their strike, which had begun on September 11, when students in the College of Business walked out of their classes and were followed by students in the Colleges of Engineering and Education. The striking students stated that they were opposed to University President Monzon who was seeking to turn a profit out of the exploitation of the students, the staff and the faculty. The leaflet cited the raising of fees and the cutting of the wages of the faculty and staff and concluded:

If we allow ourselves to be taken advantage of and place our hope in promises, not only will we be victims, not only will our brothers and sisters who will study and follow after us [be victims], but also our parents who have with great difficulty worked day and night in the fields and factories to pay for our education. Remember our poor parents … rise up!

This fight is not just for students, this is for everyone! Professors, workers, and students.

A footnote among the many stories coming out of the First Quarter Storm was that of Francisco Opao, a working student at FEATI, whose foot was shot on January 30. He had not seen his provincial parents in years because he could not afford to go home, yet he had nowhere to stay in Greater Manila and was commuting a great distance each day to school. His story was representative of the majority of the student population.

Sison insisted in his article over the space of two and half pages that the “student power” movement was the work of the KM. Sison claimed that “the Kabataang Makabayan has been able to anticipate and plan the development of the national student protest movement in the Philippines.” He could not provide a single concrete example of this, precisely because none existed.

Sison turned to the question of the political orientation of the student protest movement. He wrote “we have always advocated the achievement of real national democracy as the goal of our struggle.” He directed students to “a comprehensive presentation of this goal … the Programme of Action of Kabataang Makabayan.” Sison referred to the struggle for this program as a “cultural revolution … It is the phase of creating the public opinion necessary for a comprehensive national democratic revolution. The struggle for national democracy cannot be won without this cultural revolution.” Sison characterized the struggle for national democracy, to be carried out by “the broad national front for national democracy among workers, peasants, urban petty bourgeoisie, and the national bourgeoisie,” as “the unifying ideology of the working class,” the “justest [sic] and most progressive class.” (56)

Rather than expand the protests of the students to a directly political struggle for free universal public education through the university level, a transitional demand responding to the immediate objective situation of the students and yet requiring socialist measures to be fully implemented, Sison presented ‘national democracy’, rather than socialism, as the ideology of the working class. His perspective was that of the petty bourgeois and he saw the striking students as such and insisted that only in an alliance with the capitalist class on the basis of nationalism could they achieve their ends.

Sison’s characterization of the student movement was mirrored in the program of the Nationalist Corps, the UP funded public outreach arm of the SDK which carried out summer community service projects as a means of implementing Mao’s ‘mass line’. They outlined their program in an April 1969 article entitled, “The Nationalist Corps and the Apathetic Student,”

The Nationalist Corps is an organization which struggles to shock the masses of apathetic and complacent students out of their smugness. …

As students we do not fully comprehend the problems of the masses because we never experience the problems the way they do. The fact that students come from a different class that is quite a departure from the class of the worker and the peasant prevents them from going through the very same experience.

Sison, the KM, and the SDK displayed the extraordinary class gulf between their perspective and program and the needs and struggles of the working class. As tens of thousands of students shut down their campuses in strikes motivated by poverty and exploitation, Sison and his co-thinkers decried the students for their “apathy” and “petty bourgeois” smugness and selfishness. They used the energy of the strikes to secure tenured positions for their allies on the UP campus and instructed the striking students downtown to redirect their protests behind the banner of nationalism.