On August 26, I delivered an online lecture, “First as Tragedy, Second as Farce: Marcos, Duterte, and the Communist Parties of the Philippines,” as part of a postdoctoral seminar series at Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in Singapore.

My talk drew on my doctoral research and examined the historical precedents for the enthusiastic support which the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) gave to the fascistic Rodrigo Duterte as he became president in 2016.

Alarmed by the political exposure, Jose Maria Sison, founder and ideological leader of the CPP, launched a campaign of lies and slander. Over the course of more than a month he has repeatedly denounced me, without a shred of evidence, as a “paid agent of the CIA” and a “wild informer for the Duterte death squads.” He has posted doctored images of me as a clown and a particularly vile caricature of Leon Trotsky and me depicted as rats about to be murdered by an angry Filipino peasant.

It is in this context that Teo Marasigan, a pseudonymous intellectual commentator with a regular “Kapirasong Kritika” column at Pinoy Weekly, published an extended criticism of my recent lecture. Marasigan entitled his response, “Scalice Come, Scalice Go,” deemed my scholarship to be “trivia,” and concluded that “it fails as an intellectual effort, but would surely please the powers that be and their butchers in the country.”

In the final analysis, Marasigan’s argument amounts to the claim that Joseph Stalin was right, and the CPP is correct in continuing his political legacy.

In making this argument, Marasigan is playing the same political role that he has adopted for over a decade. He has long been known for his ability to dress up the political line of the CPP, which he terms “the Philippine Left,” with quotes in his column from the likes of Lukács, Gramsci, Žižek, Althusser, and Frederic Jameson. If you look back through his writing, you will find that it closely follows the zigs and zags in the political alignment of the CPP, and provides it with a certain academic window dressing.

Thus, in mid-2016, as both the CPP and the national democratic movement enthusiastically welcomed Duterte’s rise to power, Marasigan published columns hailing the supposedly progressive aspects of Duterte’s policies. He wrote “Pero maraming pahayag at hakbangin si Duterte na para sa masang anakpawis at sambayanang Pilipino” [Duterte has many statements and measures on behalf of the oppressed masses and the Filipino people]. Joma Sison made similar statements, and publicly declared that he was “proud of Duterte.”

Marasigan gave these claims a pseudo-intellectual veneer. He wrote the statement above beneath a passage drawn, without explanation, from Lukács’ History and Class Consciousness, speaking of Marxism as “aspirations toward society in its totality,” and depicting the recognition of Duterte’s progressive policies as part of this “Marxist” “totalizing.”

Marasigan’s function is to provide the trappings of academia and intellectual discourse to the political line of the CPP. He delivers a jargon-laden rendition of their shifting alliances and slanderous attacks. His citations do not clarify his arguments but serve a fundamentally performative function. “Kapirasong Kritika” makes for generally unedifying reading and, like the political line of the party itself, it ages poorly.

Behind all of his slanders against me, Joma Sison is doubling down on his Stalinism. Marasigan is tail-ending this and providing it with a footnote or two.

A blundering, dishonest approach

A serious response to my scholarship cannot base itself exclusively on my public lecture, which was aimed at a popular audience. I have dedicated a decade to the study of the Communist Party of the Philippines and have written a publicly available doctoral dissertation of nearly one thousand pages on the subject.

Marasigan flagrantly ignored this. He never examined my bibliography or footnotes, yet he presented a criticism of my use of sources. He dismisses my scholarship as “trivia,” yet he never, in fact, read anything that I wrote. There is no innocent explanation for this; it is a fundamentally dishonest approach.

Marasigan claims that my source material, the contemporary written record, consisted exclusively of pamphlets and fliers and similar ephemera but did not include the more significant works of the party. He writes: “The ‘contemporary written record’ definitely has its uses, but must be counterposed with the more important documents.”

This is completely false. I read and examined, in excruciating detail, every extant work published by both the CPP and the PKP in the 1960s and 1970s. I dedicated an entire chapter, more than any prior scholar, to a close reading of Philippine Society and Revolution, situating this core document of the party in its historical context. I engaged in a similar fashion with Specific Characteristics of our People’s War and Rectify Errors and Rebuild the Party, and other comparable works.

I read every extant edition of every text for I discovered very quickly that in later printings the party repeatedly and dishonestly redacted its own writings to hide their earlier political perspective.

For all of Marasigan’s talk of the “more important documents” of the party, it appears that he himself has not read them. Marasigan dismisses my citation of a passage from a 1967 speech, in which Joma Sison focused on the imperative of establishing ties with the “national bourgeoisie,” as “an obscure Sison essay.” It was nothing of the sort. The quote is from the “Nationalist as Political Activist,” a central reading in the 1967 volume, Struggle for National Democracy, which was the mandatory text assigned to the entire national democratic movement during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The crowning falsehood of this blundering and dishonest examination of my scholarship is Marasigan’s claim that I am “leery of going into details about the history of the Philippine Left.” No prior scholar has ever gone with such meticulous care into the “details” of the history of the Communist Parties of the Philippines.

The defense of Stalinism

Marasigan’s misrepresentations serve a particular end and the heart of Marasigan’s essay is the defense of the political legacy of Stalinism.

I opened my lecture by addressing Sison’s slanderous attacks against me, and concluded with an impassioned appeal “in defense of civil discourse, of democratic and public discussion, of verifiable evidence, of logical arguments and defence of democracy and historical truth.” Marasigan writes that he too “seeks to uphold these very principles.” He declares this without making any effort to distance himself from Sison’s depictions of me as a rat, a wild informer for the death squads, a clown, and a CIA agent. The banner of civil discourse cannot be so cheaply claimed.

More importantly, while Marasigan states that he desires to defend “democracy and historical truth,” he dedicates his essay to defending the politics of Joseph Stalin as correct and the murder of political dissent as historically justified.

In his defense of the CPP’s historical legacy, Marasigan does not claim that the party was not Stalinist, but asserts rather that Stalin was right. He approvingly quotes from the 1992 CPP document, Stand for Socialism against Modern Revisionism, “Stalin’s merits within his own period of leadership are principal and his demerits are secondary. He stood on the correct side and won all the great struggles to defend socialism such as those against the Left opposition headed by Trotsky…”

This is an endorsement of mass murder. Stalin systematically annihilated the Left Opposition, which was headed by Leon Trotsky and which defended the Marxist perspective of world socialist revolution against its Stalinist betrayal, Socialism in One Country. By 1937 a majority of the old Bolsheviks who had carried out the 1917 revolution had been murdered.

Marasigan’s essay included a photograph taken during the Eighth Congress of the Russian Communist Party in February 1919. Like so many photographs of the time it is evidence of the political crimes of Stalin, and it is worth examining.

In the bottom row, from left to right, we find: Ivar Smilga, a member of the Left Opposition, he was executed in February 1938 by a Stalinist show trial with a bullet to the back of the head; Vasily Schmidt, executed January 28 1938; Sergey Zorin, Left Opposition, shot September 10 1937.

In the middle row, again from left to right: Grigory Yevdokimov, United Opposition, shot August 25 1936; Stalin, the author of these crimes; Lenin, whose death in 1924 was seized upon by Stalin in his consolidation of power; Mikhail Kalinin, who famously survived the purges, but whose wife, Ekaterina Kalinina, was arrested and tortured as a “Trotskyite” in 1938 and sentenced to fifteen years in a labor camp; Pyotr Smorodin, executed February 25 1939.

And in the upper row, left to right: Pavel Malkov, he survived the purges; Eino Rahja, died of illness; Sultan-Galiev, executed January 28 1940; Pyotr Zalutsky, a member of the United Opposition, executed January 10 1937; Yakov Drobnis, Left Opposition, executed February 1 1937; Mikhail Tomsky, committed suicide in the face of the first Moscow Trial. He was posthumously charged with high treason by the show trials of 1938. Moisie Kharitonov, Left Opposition, died in a prison camp in 1948; Adolf Joffe, Left Opposition, he committed suicide when Trotsky was expelled from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union; David Riazanov, founder of the Marx-Engels Institute, executed January 21 1938 as a “Trotskyite”; Aleksei Badayev, he survived the purges; Leonid Serebryakov, Left Opposition, executed February 1 1937; Mikhail Lashevich, Left Opposition, committed suicide, August 30 1928.

Of the eighteen men in the photograph, excluding Lenin and Stalin, ten were executed on the orders of Stalin, one died in a prison camp, and three more committed suicide in the face of Stalinist persecution. A majority of the men in the picture opposed Stalin, and seven were members of the Left Opposition, led by Trotsky. Many of the murdered were truly great men. More knowledge of the writings of Marx and Engels died with Riazanov than was known by any other individual in history. Looking at these faces, I recall a line from a 1935 poem by Victor Serge, “O rain of stars in the darkness / constellation of dead brothers!”

This is the legacy that Sison and the CPP uphold with their claims that Stalin “stood on the correct side.” Whatever scholastic niceties there may be to his formulations, Marasigan is unequivocally defending this legacy as well.

Defenders of the Menshevik two-stage theory

The two-stage theory of revolution, the perspective of the old Menshevik party, was rehabilitated in service to the privileged interests of the Stalinist bureaucracy. Using this theory, the Stalinist Communist Parties around the globe instructed workers that the tasks of the revolution were not socialist, but remained national and democratic in character. There was thus, they argued, a progressive section of the capitalist class, the “national bourgeoisie,” with which the workers should ally. Just as he upholds the CPP’s defense of the murder of the Left Opposition, Marasigan follows the CPP in defending the perspective of a two-stage revolution.

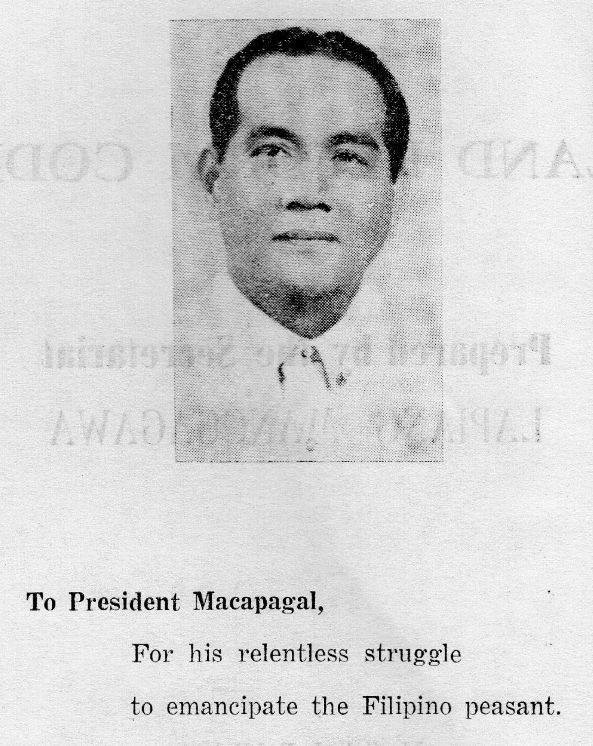

On the basis of this program, Sison, then in the leadership of the PKP, publicly endorsed President Diosdado Macapagal as a “revolutionary.” He instructed the Kabataang Makabayan (Nationalist Youth), Lapiang Manggagawa (Workers Party), and Malayang Samahan ng mga Magsasaka (Free Federation of Peasants) to support Ferdinand Marcos in the 1965 presidential election. When Sison was expelled from the PKP in 1967, he founded a new party, the CPP, and used it to ally the growing mass movement with the ruling class politicians of the Liberal Party. The PKP, meanwhile, on the basis of the same two-stage theory, supported Marcos’ imposition of martial law. It was on the basis of this perspective that the CPP gave its support to Duterte in 2016.

Marasigan writes of my historical exposure of the alliances formed by the CPP that “the Philippine Left’s relations with the said politicians are nothing new for activists and even observers of Philippine politics, Scalice’s elan of dropping bombshells notwithstanding.” This is both dishonest and an extraordinary admission. It is dishonest to claim that “activists and observers of Philippine politics” know of Sison’s support for Macapagal and Marcos. Most would not know. More important than this lie, however, is the truth contained in Marasigan’s statement: the CPP and the national democratic movement engage in “relations” with ruling class politicians with a predictable regularity. It is, in fact, nothing new.

Having stated that the party routinely establishes relations with elite politicians, Marasigan contradicts himself elsewhere in his essay when he claims that the party’s support for the “national bourgeoisie” is extended only to “small businessmen,” and not to the so-called big comprador bourgeoisie closely tied to foreign capital. This distinction is a longstanding claim of Stalinism to which Trotsky responded in May 1927:

Leon Trotsky on China (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1976), 177. It would further be profound naiveté to believe that an abyss lies between the so-called comprador bourgeoisie, that is, the economic and political agency of foreign capital in China, and the so-called national bourgeoisie. No, these two sections stand incomparably closer to each other than the bourgeoisie and the masses of workers and peasants.

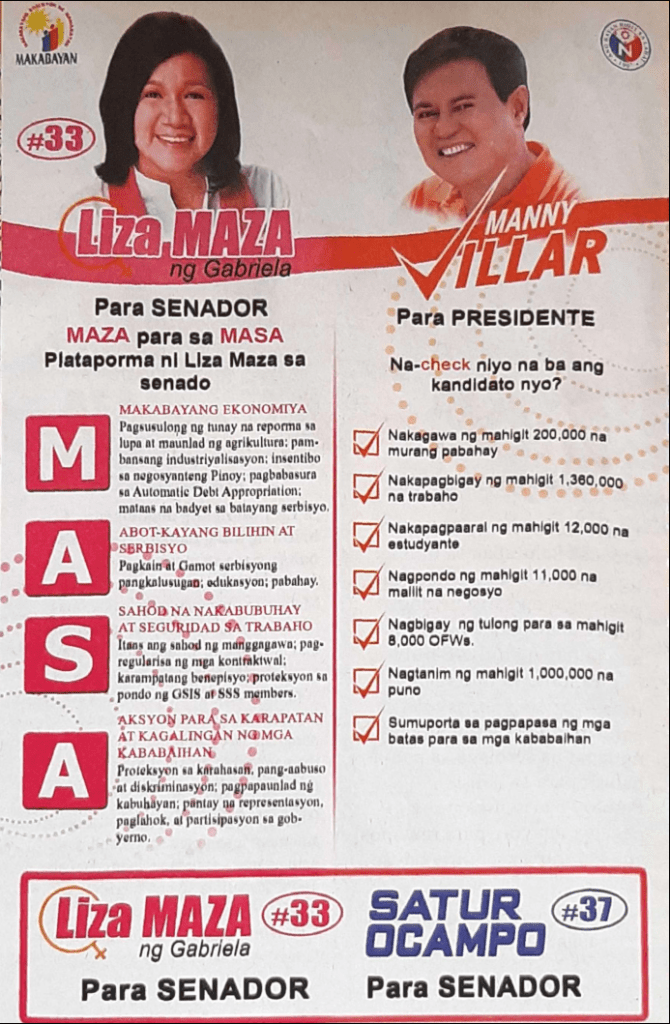

In truth there is almost no permanent, concrete content in the writings of the CPP to these ostensible divisions in the bourgeoisie. The party has at different historical junctures allied with almost every faction of the ruling elite in the country in the name of the “progressive section of the national bourgeoisie.” The label justified the support of the national democratic movement for real estate tycoon Manny Villar just as easily as it did Duterte. It is only when relations break down that these erstwhile allies become once again “compradors,” and perhaps even “fascists.”

Sison and Marasigan both claim that the party’s relations with factions of the ruling elite entail both “unity” and “struggle.” The national democratic movement united with Duterte, campaigned for him, proclaimed him progressive, pledged their “full support,” and the CPP committed itself to assisting with his war on drugs, but they also “struggled” with him, attempting to pressure him to the left.

This was an unmitigated betrayal of the working class. The task of a revolutionary leadership was to insistently warn of the imminent danger posed by the fascistic Duterte, and to organize an independent movement of workers for their own, socialist interests.

The CPP is fundamentally opposed to the political independence of the working class and sought to secure concessions from the Duterte administration by means of “unity and struggle.” In the process they peddled the lie that the right-wing populist president was someone who could genuinely defend the interests of the working class and peasantry. The fundamental task of the party to educate the working class was, to Sison and the party leadership, irrelevant. The real goal of the CPP was the negotiation and exacting concessions.

None of this is unique to the Philippines; it is the legacy of Stalinism around the globe. Marasigan in his defense of the Stalinist two-stage theory would have joined the Mensheviks in supporting the bourgeois Cadet party in 1905–6. His perspective aligns with that of Stalin and Kamenev who, in March 1917, gave support to the bourgeois provisional government and were castigated severely by Lenin in April. Marasigan’s arguments are the same as those deployed by Stalin in his insistence that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1925–27 ally with Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang, as the representatives of the national bourgeoisie. Chiang used this support to turn his troops on the Chinese working class, slaughtering them in Shanghai and elsewhere.

Each of these alliances with the capitalist class, and the hundreds of similar deals concluded by Stalinist parties over the course of the twentieth century, were a betrayal of the working class.

The falsification of Marxism

Marasigan attempts to depict this perspective as Marxist with a handful of quotations from Marx and Lenin which he has torn out of context. The historical record, however, is clear. Marxists have always viewed the safeguarding and nurturing of the political independence of the working class as the paramount revolutionary task. Only in this way can workers become aware of their strength as a class and develop socialist consciousness.

Marx and Engels in their 1850 Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League, insisted on the political independence of the working class in opposition to the calls of the “democratic petty bourgeoisie” using “social democratic phrases” for “general unity.” Lenin and Trotsky, despite their political differences in 1905–6, were unanimous in their opposition to an alliance with the bourgeois Cadet party.

Marasigan attempts to justify the CPP’s alliances with representatives of the political elite as a means of exploiting divisions in the ruling class. Marxists have always paid careful attention to divisions within the ruling class as a means of consolidating and advancing the interests of the working class.

While Lenin was in hiding in August 1917, Trotsky was alert to the divisions in the Russian ruling class and directed the Bolshevik party and the Petrograd Soviet against the coup threat from General Kornilov before turning to the removal of Prime Minister Kerensky. At no point, however, did they unite with Kerensky or endorse his political legitimacy.

Stalinists, in contrast, exploit contradictions in the ruling class as a means of securing an alliance with one of the contending sections of the elite. Marasigan claims that the writings of Mao Zedong are “informed by the Chinese revolution’s wealth of experiences in building united fronts.”

For a Marxist, the united front is a critical strategy for uniting the working class, in its various parties, against a common enemy, without any mingling of organizations or mixing of banners. Trotsky urgently called for a united front of the German working class, organized in the Communist Party (KPD) and the Social Democratic Party (SPD) in the early 1930s, against the imminent of danger of Nazism. The Stalinist KPD opposed this call, denounced the social democrats as “social fascists,” and claimed that the KPD would rise to power after Hitler. They split the working class and allowed Hitler and the Nazis to take power without a shot.

In opposition to the Marxist strategy presented by Trotsky, the “united fronts” of Mao were alliances with the capitalist class and with US imperialism based on Stalin’s Popular Front policy that subordinated the working class to sections of the bourgeoisie with devastating consequences in Spain and France in the 1930s.

In 1937, after the disastrous results of the support for Chiang Kai-shek and the KMT a decade earlier, Mao arranged a new alliance with the KMT in opposition to the Japanese invasion. Chiang repeatedly attacked the CCP forces, but Mao insisted on maintaining the “united front.” In the wake of World War II, Mao led the CCP to attempt to form a united government with the KMT. It was not until 1947, as Chiang’s forces were collapsing in the face of economic upheaval and workers’ strikes, that Mao gave up on this strategy.

In 1971, as the Stalinist bureaucracies in Moscow and Beijing doubled down on their nationalist program of Socialism in One Country, Mao turned to Nixon and Kissinger to establish a de-facto alliance with Washington against the threat of a possible Soviet invasion. Having opened relations with US imperialism, he established friendly ties with the Marcos dictatorship and with Pinochet. Chilean President Salvador Allende had been supported by the Communist Party of Chile, which had close ties to Moscow, and thus Mao and the CCP immediately welcomed Pinochet’s brutal coup and the murder of the Chilean Communist Party.

Marasigan sets up a straw man claiming that I argue that Sison and the CPP are simply flunkies of the Beijing bureaucracy. In fact, its unprincipled relations with various factions of the Philippine bourgeoisie have been paralleled by its equally unprincipled relations on the world stage. As it sought to maneuver and extract benefits from the Stalinist bureaucracies in Beijing and Moscow, it has endorsed monstrous betrayals of the working class.

During this phase of Maoism from 1965 to 1971, as the CCP exported arms and ideology throughout the region, it served the interests of Sison and the CPP to echo every shift of the political line of Beijing in the pages of the party paper, Ang Bayan. As Mao embraced Nixon and Kissinger and established friendly ties with the martial law regime of Marcos, the CPP hailed these betrayals as “revolutionary victories” of Mao Zedong’s “proletarian foreign policy.”

Despite this rhetoric, the CPP was left utterly isolated by the changed political line of Beijing. The party turned inward, accentuating its nationalism. Sison continued to look for international allies. In the mid-1980s he dropped his accusations of revisionism against the Soviet bureaucracy and hailed the policies of Mikhail Gorbachev. Nothing came of this effort, however. In 1989, the CPP, still hoping for ties with Beijing, supported the CCP’s brutal attack on Chinese workers and youth at Tiananmen claiming it was a necessary struggle against revisionism.

For Sison and the CPP leadership, the working class exists as a bargaining chip to use in negotiations with various sections of the capitalist elite. The anti-Marxist theories of Stalinism serve the dual function of assisting the party in retaining control over the working class, and justifying its long history of class collaboration and betrayal.

Like Sison, Marasigan uses the term “Philippine Left” with a proprietary sensibility. There is no left but the CPP, and Sison is its prophet. This is why my historical exposure of the party’s role stung Sison so badly, for it demonstrated that neither he nor his party merited the name.

Genuine left politics are predicated upon the independence of the working class fighting for its own interests. These interests are international and not national in character. The allies of the Filipino working class are the Chinese and American working class and not Filipino capitalists.

Marasigan concluded by repeating Sison’s claim that my scholarship will be welcomed “in military indoctrination seminars” and will “surely please the powers that be and their butchers in the country.” This is a slander. The historical defense of the independence of the working class serves no interests other than those of the working class itself.

As for support from the military, it is Sison himself who is publicly reaching out to coup-plotting layers in the military brass, both its “patriotic and pro-US” sections, in the hopes of getting them to withdraw support from Duterte. Should Sison succeed in this, Marasigan will no doubt be on hand to write an article dressing up the policy in the trappings of intellectual charlatanry.