An odd, unpleasant photograph was taken forty-five years ago today. Imelda Marcos, the conjugal head of a two year old military dictatorship, intimately greeted the aged Chairman Mao who openly ogled the straightcut neckline of her terno. The martial law regime of the Marcoses, imposed on the Philippines in September 1972, was systematically brutalizing the country’s working class and peasantry. Mao recognized the legitimacy of the Marcos dictatorship and pledged that the Communist Party of China (CCP) would not interfere in the internal affairs of the country. The Maoist Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) hailed Imelda’s visit as a revolutionary victory.

In September 1974, Imelda Marcos led a diplomatic mission to China to open formal ties between Beijing and Manila. She was fêted throughout the country, and met on several occasions with Zhou Enlai and once with Mao Zedong. Marcos was able to secure a deal for the purchase of Chinese oil, which in the midst of the OPEC crisis was desperately sought, and China committed to purchase Philippine exports. Arrangements were made for a state visit by Ferdinand Marcos to China in 1975. The visit of Imelda Marcos to Beijing entailed the recognition by the CCP of the legitimacy of the Marcos’ martial law regime. It also, in keeping with the CCP’s Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, meant that Beijing was committing to a policy of non-interference in the internal matters of the Philippines, something Ferdinand Marcos publicly announced, informing the press that “certain Lin Biao elements were training cadre for Philippine rebel movements but added he was satisfied with Prime Minister Zhou Enlai’s assurances that this would not continue.”

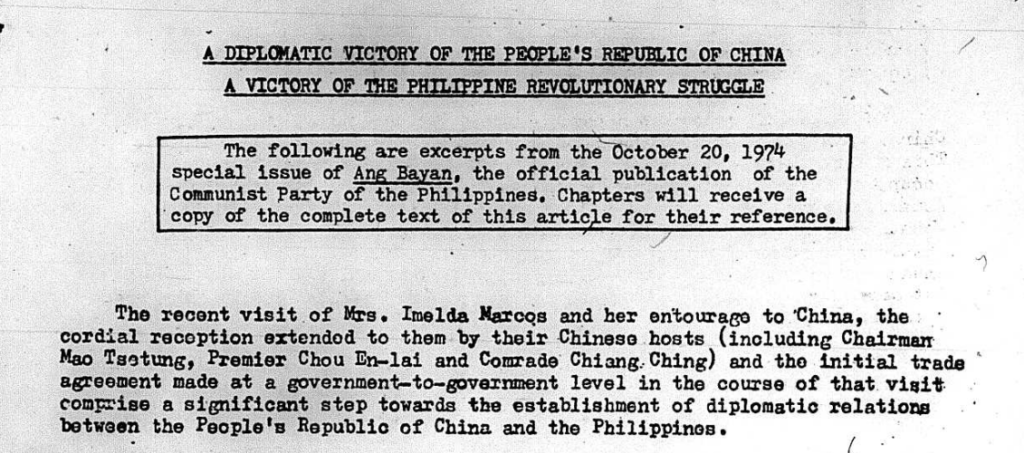

José Ma. Sison, head of the Maoist Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), in an article published in the party’s newspaper, Ang Bayan, on October 20 1974, hailed Imelda Marcos’ visit to China as “A Diplomatic Victory of the People’s Republic of China, A Victory of the Philippine Revolutionary Struggle.” He wrote that there were “three types of people” in the Philippines who were “disturbed in one way or another about the developing relations between China and the Philippines:” “those who wish to live in the past and fail to recognize that even the United States has already pronounced her policy to move towards the normalization of relations with China;” “the local revisionist renegades who accuse the Communist Party of the Philippines of being inconsistent in opposing Soviet relations with the Philippines and yet endorsing China’s relations with the Philippines;” and “well-meaning people who fear that China’s friendly relations now with the Philippines would serve to help the fascist puppet dictatorship and adversely affect the Philippine revolutionary struggle.” It was this last group, that is to say, the members and supporters of the CPP who were troubled by Marcos being welcomed in Beijing, that Sison was most concerned to persuade.

Why did the CPP support relations between Manila and Beijing and oppose relations with Moscow? Sison answered that the Soviet Union was one of the world’s two superpowers and was looking to exploit and plunder the Philippines. The USSR was, according to Sison, a graver danger than Washington. He wrote “given a longer leash in the country, this superpower will not only be one more imperialist power on the back of the Filipino people but will possibly turn out to be the principal foreign power exploiting and oppressing the people.” Did not Mao’s welcome to Imelda Marcos and her entourage entail Beijing’s recognition of the legitimacy of Marcos’ anti-democratic dictatorship? Sison responded with a question: “who should represent the Philippine reactionary government now in dealing with China? More than two years have passed since the Marcos rightist coup but we do not yet see other reactionaries deposing Marcos.” From Sison’s perspective either Marcos or some other reactionary were the only legitimate representatives with whom Mao should deal. As no other reactionary figures were available, Beijing needed to deal with Marcos. He continued, “We simply have to recognize the fact that Marcos remains the chieftain of the reactionary government and that there is no way for China to develop country-to-country relations with the Philippines except by dealing with his government.”

In a labored and dishonest argument, Sison depicted the ties between Beijing and Manila as a brilliant strategic maneuver on the part of China. Beijing was exploiting contradictions between the United States and the Soviet Union by opening up ties with Marcos. He held up Stalin’s pact with Hitler as a positive example of such strategic diplomacy, claiming that Stalin had “defeated the maneuver of the other imperialist powers” through his deal with Nazi Germany. Sison acknowledged that Beijing’s ties with Manila were negotiated on the basis of the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, the third principle of which was “noninterference in each other’s internal affairs.” The significance of this clause was immense. It meant that the CCP would not fund or supply the CPP in any way, and it further meant that Marcos could continue martial law and have the military suppress the CPP, and the working class and peasantry generally, and Beijing would not interfere. China would no longer serve as the Yan’an of world revolution.

Sison did not acknowledge these implications. He insisted that “China has never bargained away principles with any superpower and has always courageously fought for her principles.” He passed over in silence the fact that China had agreed with Marcos that it would not in any way support the CPP or oppose his regime. Sison was aware of this, however, and his next paragraph addressed the isolation of the Philippine revolution. He depicted this isolation as a nationalist necessity and not the result of Stalinist betrayal, writing that “Revolution cannot be exported to the Philippines via Sino-Philippine relations. … Though Sino-Philippine relations can shed some favorable influence, the Philippine revolution must be the creation of the millions upon millions of the Filipino people and must be carried out according to Philippine conditions.”

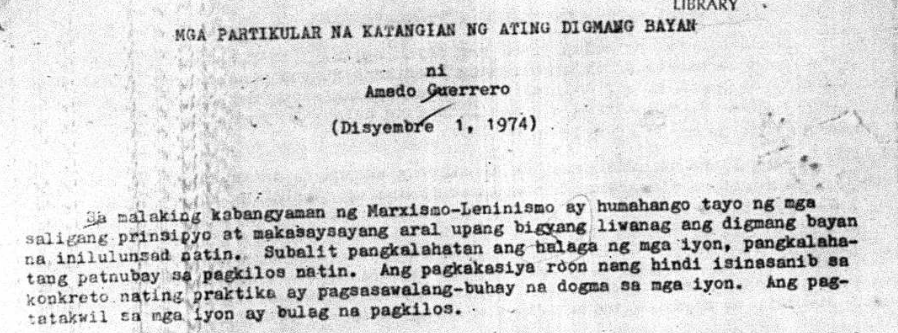

Beijing had struck a bargain with Marcos, opening trade and diplomatic relations with the dictatorship, and Mao had agreed that China would not in any way interfere in Marcos dictatorship, which was an internal matter. Sison heralded this betrayal as “A Diplomatic Victory of the People’s Republic of China, A Victory of the Philippine Revolutionary Struggle.” The CPP was now completely isolated, and the Philippine revolution, Sison stated, needed to be conducted “according to Philippine conditions.” It was to this proposition that Sison would turn in his next significant statement, Specific Characteristics of our People’s War.

[Further details and citations can be found in my doctoral dissertation.]